Mutation

-

First Mutations in Human Life Discovered

The earliest mutations of human life have been observed by research team led by the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute and their collaborators. Analyzing genomes from adult cells, the scientists could look back in time to reveal how each embryo developed.

Research team of the Sanger Institute including Professor Young Seok Ju of the Graduate School of Medical Science and Engineering at KAIST published an article of “Somatic Mutations Reveal Asymmetric Cellular Dynamics in the Early Human Embryo” in Nature on March 22.

The study shows that from the two-cell stage of the human embryo, one of these cells becomes more dominant than the other and leads to a higher proportion of the adult body.

A longstanding question for researchers has been what happens in the very early human development as this has proved impossible to study directly. Now, researchers have analyzed the whole genome sequences of blood samples (collected from 279 individuals with breast cancer) and discovered 163 mutations that occurred very early in the embryonic development of those people.

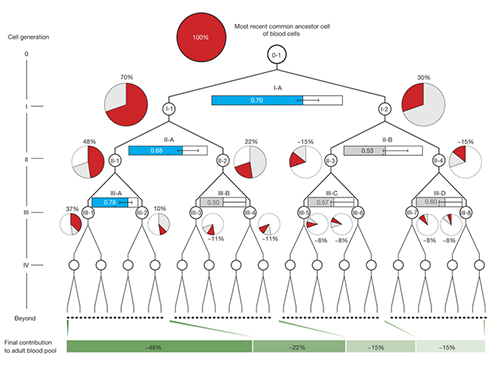

Once identified, the researchers used mutations from the first, second and third divisions of the fertilized egg to calculate which proportion of adult cells resulted from each of the first two cells in the embryo. They found that these first two cells contribute differently to the whole body. One cell gives rise to about 70 percent of the adult body tissues, whereas the other cell has a more minor contribution, leading to about 30percent of the tissues. This skewed contribution continues for some cells in the second and third generation too.

Originally pinpointed in normal blood cells from cancer patients, the researchers then looked for these mutations in cancer samples that had been surgically removed from the patients during treatment. Unlike normal tissues composed of multiple somatic cell clones, a cancer develops from one mutant cell. Therefore, each proposed embryonic mutation should either be present in all of the cancer cells in a tumor, or none of them. This proved to be the case, and by using these cancer samples, the researchers were able to validate that the mutations had originated during early development.

Dr. Young Seok Ju, first author from the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute and KAIST, said: "This is the first time that anyone has seen where mutations arise in the very early human development. It is like finding a needle in a haystack. There are just a handful of these mutations, compared with millions of inherited genetic variations, and finding them allowed us to track what happened during embryogenesis."

Dr. Inigo Martincorena, from the Sanger Institute, said: "Having identified the mutations, we were able to use statistical analysis to better understand cell dynamics during embryo development. We determined the relative contribution of the first embryonic cells to the adult blood cell pool and found one dominant cell - that led to 70 percent of the blood cells - and one minor cell. We also sequenced normal lymph and breast cells, and the results suggested that the dominant cell also contributes to these other tissues at a similar level. This opens an unprecedented window into the earliest stages of human development."

During this study, the researchers were also able to measure the rate of mutation in early human development for the first time, up to three generations of cell division. Previous researchers had estimated one mutation per cell division, but this study measured three mutations for each cell doubling, in every daughter cell.

Mutations during the development of the embryo occur by two processes - known as mutational signatures 1 and 5. These mutations are fairly randomly distributed through the genome, and the vast majority of them will not affect the developing embryo. However, a mutation that occurs in an important gene can lead to disease such as developmental disorders.

Professor Sir Mike Stratton, lead author on the paper and Director of the Sanger Institute, said: "This is a significant step forward in widening the range of biological insights that can be extracted using genome sequences and mutations. Essentially, the mutations are archaeological traces of embryonic development left in our adult tissues, so if we can find and interpret them, we can understand human embryology better. This is just one early insight into human development, with hopefully many more to come in the future."

(Figure 1. Detection of somatic mutations acquired in early human embryogenesis )

(Figure 2. Unequal contributions of early embryonic cells to adult somatic tissues )

2017.03.23 View 7800

First Mutations in Human Life Discovered

The earliest mutations of human life have been observed by research team led by the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute and their collaborators. Analyzing genomes from adult cells, the scientists could look back in time to reveal how each embryo developed.

Research team of the Sanger Institute including Professor Young Seok Ju of the Graduate School of Medical Science and Engineering at KAIST published an article of “Somatic Mutations Reveal Asymmetric Cellular Dynamics in the Early Human Embryo” in Nature on March 22.

The study shows that from the two-cell stage of the human embryo, one of these cells becomes more dominant than the other and leads to a higher proportion of the adult body.

A longstanding question for researchers has been what happens in the very early human development as this has proved impossible to study directly. Now, researchers have analyzed the whole genome sequences of blood samples (collected from 279 individuals with breast cancer) and discovered 163 mutations that occurred very early in the embryonic development of those people.

Once identified, the researchers used mutations from the first, second and third divisions of the fertilized egg to calculate which proportion of adult cells resulted from each of the first two cells in the embryo. They found that these first two cells contribute differently to the whole body. One cell gives rise to about 70 percent of the adult body tissues, whereas the other cell has a more minor contribution, leading to about 30percent of the tissues. This skewed contribution continues for some cells in the second and third generation too.

Originally pinpointed in normal blood cells from cancer patients, the researchers then looked for these mutations in cancer samples that had been surgically removed from the patients during treatment. Unlike normal tissues composed of multiple somatic cell clones, a cancer develops from one mutant cell. Therefore, each proposed embryonic mutation should either be present in all of the cancer cells in a tumor, or none of them. This proved to be the case, and by using these cancer samples, the researchers were able to validate that the mutations had originated during early development.

Dr. Young Seok Ju, first author from the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute and KAIST, said: "This is the first time that anyone has seen where mutations arise in the very early human development. It is like finding a needle in a haystack. There are just a handful of these mutations, compared with millions of inherited genetic variations, and finding them allowed us to track what happened during embryogenesis."

Dr. Inigo Martincorena, from the Sanger Institute, said: "Having identified the mutations, we were able to use statistical analysis to better understand cell dynamics during embryo development. We determined the relative contribution of the first embryonic cells to the adult blood cell pool and found one dominant cell - that led to 70 percent of the blood cells - and one minor cell. We also sequenced normal lymph and breast cells, and the results suggested that the dominant cell also contributes to these other tissues at a similar level. This opens an unprecedented window into the earliest stages of human development."

During this study, the researchers were also able to measure the rate of mutation in early human development for the first time, up to three generations of cell division. Previous researchers had estimated one mutation per cell division, but this study measured three mutations for each cell doubling, in every daughter cell.

Mutations during the development of the embryo occur by two processes - known as mutational signatures 1 and 5. These mutations are fairly randomly distributed through the genome, and the vast majority of them will not affect the developing embryo. However, a mutation that occurs in an important gene can lead to disease such as developmental disorders.

Professor Sir Mike Stratton, lead author on the paper and Director of the Sanger Institute, said: "This is a significant step forward in widening the range of biological insights that can be extracted using genome sequences and mutations. Essentially, the mutations are archaeological traces of embryonic development left in our adult tissues, so if we can find and interpret them, we can understand human embryology better. This is just one early insight into human development, with hopefully many more to come in the future."

(Figure 1. Detection of somatic mutations acquired in early human embryogenesis )

(Figure 2. Unequal contributions of early embryonic cells to adult somatic tissues )

2017.03.23 View 7800 -

Mutations Occurring Only in Brain Responsible for Intractable Epilepsy Identified

KAIST researchers have discovered that brain somatic mutations in MTOR gene induce intractable epilepsy and suggest a precision medicine to treat epileptic seizures.

Epilepsy is a brain disorder which afflicts more than 50 million people worldwide. Many epilepsy patients can control their symptoms through medication, but about 30% suffer from intractable epilepsy and are unable to manage the disease with drugs. Intractable epilepsy causes multiple seizures, permanent mental, physical, and developmental disabilities, and even death. Therefore, surgical removal of the affected area from the brain has been practiced as a treatment for patients with medically refractory seizures, but this too fails to provide a complete solution because only 60% of the patients who undergo surgery are rendered free of seizures.

A Korean research team led by Professor Jeong Ho Lee of the Graduate School of Medical Science and Engineering at the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST) and Professor Dong-Seok Kim of Epilepsy Research Center at Yonsei University College of Medicine has recently identified brain somatic mutations in the gene of mechanistic target of rapamycin (MTOR) as the cause of focal cortical dysplasia type II (FCDII), one of the most important and common inducers to intractable epilepsy, particularly in children. They propose a targeted therapy to lessen epileptic seizures by suppressing the activation of mTOR kinase, a signaling protein in the brain. Their research results were published online in Nature Medicine on March 23, 2015.

FCDII contributes to the abnormal developments of the cerebral cortex, ranging from cortical disruption to severe forms of cortical dyslamination, balloon cells, and dysplastic neurons. The research team studied 77 FCDII patients with intractable epilepsy who had received a surgery to remove the affected regions from the brain. The researchers used various deep sequencing technologies to conduct comparative DNA analysis of the samples obtained from the patients’ brain and blood, or saliva. They reported that about 16% of the studied patients had somatic mutations in their brain. Such mutations, however, did not take place in their blood or saliva DNA.

Professor Jeong Ho Lee of KAIST said, “This is an important finding. Unlike our previous belief that genetic mutations causing intractable epilepsy exist anywhere in the human body including blood, specific gene mutations incurred only in the brain can lead to intractable epilepsy. From our animal models, we could see how a small fraction of mutations carrying neurons in the brain could affect its entire function.”

The research team recapitulated the pathogenesis of intractable epilepsy by inducing the focal cortical expression of mutated mTOR in the mouse brain via electroporation method and observed as the mouse develop epileptic symptoms. They then treated these mice with the drug called “rapamycin” to inhibit the activity of mTOR protein and observed that it suppressed the development of epileptic seizures with cytomegalic neurons.

“Our study offers the first evidence that brain-somatic activating mutations in MTOR cause FCDII and identifies mTOR as a treatment target for intractable epilepsy,” said co-author Dr. Dong-Seok Kim, a neurosurgeon at Yonsei Medical Center with the country’s largest surgical experiences in treating patients with this condition.

The research paper is titled “Brain somatic mutations in MTOR cause focal cortical dysplasia type II leading to intractable epilepsy.” (Digital Object Identifier #: 10.1038/nm.3824)

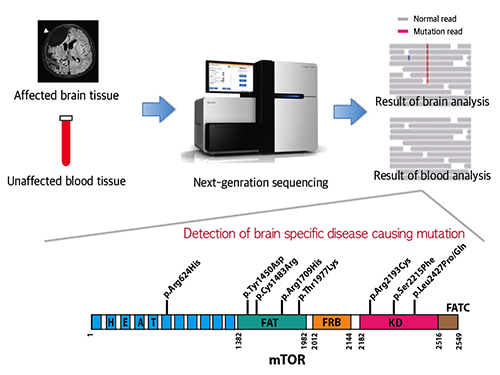

Picture 1: A schematic image to show how to detect brain specific mutation using next-generation sequencing technology with blood-brain paired sample. Simple comparison of non-overlapping mutations between affected and unaffected tissues is able to detect brain specific mutations.

Picture 2: A schematic image to show how to generate focal cortical dysplasia mouse model. This mouse model open the new window of drug screening for seizure patients.

Picture 3: Targeted medicine can rescue the focal cortical dysplasia symptoms including cytomegalic neuron & intractable epilepsy.

2015.03.25 View 14235

Mutations Occurring Only in Brain Responsible for Intractable Epilepsy Identified

KAIST researchers have discovered that brain somatic mutations in MTOR gene induce intractable epilepsy and suggest a precision medicine to treat epileptic seizures.

Epilepsy is a brain disorder which afflicts more than 50 million people worldwide. Many epilepsy patients can control their symptoms through medication, but about 30% suffer from intractable epilepsy and are unable to manage the disease with drugs. Intractable epilepsy causes multiple seizures, permanent mental, physical, and developmental disabilities, and even death. Therefore, surgical removal of the affected area from the brain has been practiced as a treatment for patients with medically refractory seizures, but this too fails to provide a complete solution because only 60% of the patients who undergo surgery are rendered free of seizures.

A Korean research team led by Professor Jeong Ho Lee of the Graduate School of Medical Science and Engineering at the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST) and Professor Dong-Seok Kim of Epilepsy Research Center at Yonsei University College of Medicine has recently identified brain somatic mutations in the gene of mechanistic target of rapamycin (MTOR) as the cause of focal cortical dysplasia type II (FCDII), one of the most important and common inducers to intractable epilepsy, particularly in children. They propose a targeted therapy to lessen epileptic seizures by suppressing the activation of mTOR kinase, a signaling protein in the brain. Their research results were published online in Nature Medicine on March 23, 2015.

FCDII contributes to the abnormal developments of the cerebral cortex, ranging from cortical disruption to severe forms of cortical dyslamination, balloon cells, and dysplastic neurons. The research team studied 77 FCDII patients with intractable epilepsy who had received a surgery to remove the affected regions from the brain. The researchers used various deep sequencing technologies to conduct comparative DNA analysis of the samples obtained from the patients’ brain and blood, or saliva. They reported that about 16% of the studied patients had somatic mutations in their brain. Such mutations, however, did not take place in their blood or saliva DNA.

Professor Jeong Ho Lee of KAIST said, “This is an important finding. Unlike our previous belief that genetic mutations causing intractable epilepsy exist anywhere in the human body including blood, specific gene mutations incurred only in the brain can lead to intractable epilepsy. From our animal models, we could see how a small fraction of mutations carrying neurons in the brain could affect its entire function.”

The research team recapitulated the pathogenesis of intractable epilepsy by inducing the focal cortical expression of mutated mTOR in the mouse brain via electroporation method and observed as the mouse develop epileptic symptoms. They then treated these mice with the drug called “rapamycin” to inhibit the activity of mTOR protein and observed that it suppressed the development of epileptic seizures with cytomegalic neurons.

“Our study offers the first evidence that brain-somatic activating mutations in MTOR cause FCDII and identifies mTOR as a treatment target for intractable epilepsy,” said co-author Dr. Dong-Seok Kim, a neurosurgeon at Yonsei Medical Center with the country’s largest surgical experiences in treating patients with this condition.

The research paper is titled “Brain somatic mutations in MTOR cause focal cortical dysplasia type II leading to intractable epilepsy.” (Digital Object Identifier #: 10.1038/nm.3824)

Picture 1: A schematic image to show how to detect brain specific mutation using next-generation sequencing technology with blood-brain paired sample. Simple comparison of non-overlapping mutations between affected and unaffected tissues is able to detect brain specific mutations.

Picture 2: A schematic image to show how to generate focal cortical dysplasia mouse model. This mouse model open the new window of drug screening for seizure patients.

Picture 3: Targeted medicine can rescue the focal cortical dysplasia symptoms including cytomegalic neuron & intractable epilepsy.

2015.03.25 View 14235