biology

-

The Dynamic Tracking of Tissue-Specific Secretory Proteins

Researchers develop a versatile and powerful tool for studying the spatiotemporal dynamics of secretory proteins, a valuable class of biomarkers and therapeutic targets

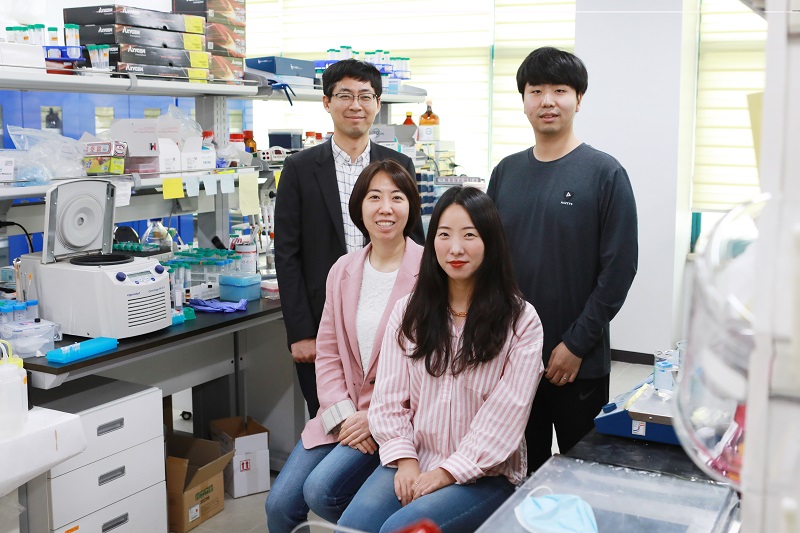

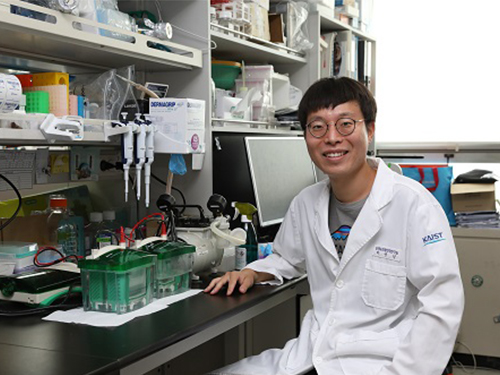

Researchers have presented a method for profiling tissue-specific secretory proteins in live mice. This method is expected to be applicable to various tissues or disease models for investigating biomarkers or therapeutic targets involved in disease progression. This research was reported in Nature Communications on September 1.

Secretory proteins released into the blood play essential roles in physiological systems. They are core mediators of interorgan communication, while serving as biomarkers and therapeutic targets.

Previous studies have analyzed conditioned media from culture models to identify cell type-specific secretory proteins, but these models often fail to fully recapitulate the intricacies of multi-organ systems and thus do not sufficiently reflect biological realities.

These limitations provided compelling motivation for the research team led by Jae Myoung Suh and his collaborators to develop techniques that could identify and resolve characteristics of tissue-specific secretory proteins along time and space dimensions.

For addressing this gap in the current methodology, the research team utilized proximity-labeling enzymes such as TurboID to label secretory proteins in endoplasmic reticulum lumen using biotin. Thereafter, the biotin-labeled secretory proteins were readily enriched through streptavidin affinity purification and could be identified through mass spectrometry.

To demonstrate its functionality in live mice, research team delivered TurboID to mouse livers via an adenovirus. After administering the biotin, only liver-derived secretory proteins were successfully detected in the plasma of the mice. Interestingly, the pattern of biotin-labeled proteins secreted from the liver was clearly distinctive from those of hepatocyte cell lines.

First author Kwang-eun Kim from the Graduate School of Medical Science and Engineering explained, “The proteins secreted by the liver were significantly different from the results of cell culture models. This data shows the limitations of cell culture models for secretory protein study, and this technique can overcome those limitations. It can be further used to discover biomarkers and therapeutic targets that can more fully reflect the physiological state.”

This work research was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea, the KAIST Key Research Institutes Project (Interdisciplinary Research Group), and the Institute for Basic Science in Korea.

-PublicationKwang-eun Kim, Isaac Park et al., “Dynamic tracking and identification of tissue-specific secretory proteins in the circulation of live mice,” Nature Communications on Sept.1,

2021(https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-25546-y)

-ProfileProfessor Jae Myoung Suh Integrated Lab of Metabolism, Obesity and Diabetes Researchhttps://imodkaist.wixsite.com/home

Graduate School of Medical Science and Engineering College of Life Science and BioengineeringKAIST

2021.09.14 View 9717

The Dynamic Tracking of Tissue-Specific Secretory Proteins

Researchers develop a versatile and powerful tool for studying the spatiotemporal dynamics of secretory proteins, a valuable class of biomarkers and therapeutic targets

Researchers have presented a method for profiling tissue-specific secretory proteins in live mice. This method is expected to be applicable to various tissues or disease models for investigating biomarkers or therapeutic targets involved in disease progression. This research was reported in Nature Communications on September 1.

Secretory proteins released into the blood play essential roles in physiological systems. They are core mediators of interorgan communication, while serving as biomarkers and therapeutic targets.

Previous studies have analyzed conditioned media from culture models to identify cell type-specific secretory proteins, but these models often fail to fully recapitulate the intricacies of multi-organ systems and thus do not sufficiently reflect biological realities.

These limitations provided compelling motivation for the research team led by Jae Myoung Suh and his collaborators to develop techniques that could identify and resolve characteristics of tissue-specific secretory proteins along time and space dimensions.

For addressing this gap in the current methodology, the research team utilized proximity-labeling enzymes such as TurboID to label secretory proteins in endoplasmic reticulum lumen using biotin. Thereafter, the biotin-labeled secretory proteins were readily enriched through streptavidin affinity purification and could be identified through mass spectrometry.

To demonstrate its functionality in live mice, research team delivered TurboID to mouse livers via an adenovirus. After administering the biotin, only liver-derived secretory proteins were successfully detected in the plasma of the mice. Interestingly, the pattern of biotin-labeled proteins secreted from the liver was clearly distinctive from those of hepatocyte cell lines.

First author Kwang-eun Kim from the Graduate School of Medical Science and Engineering explained, “The proteins secreted by the liver were significantly different from the results of cell culture models. This data shows the limitations of cell culture models for secretory protein study, and this technique can overcome those limitations. It can be further used to discover biomarkers and therapeutic targets that can more fully reflect the physiological state.”

This work research was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea, the KAIST Key Research Institutes Project (Interdisciplinary Research Group), and the Institute for Basic Science in Korea.

-PublicationKwang-eun Kim, Isaac Park et al., “Dynamic tracking and identification of tissue-specific secretory proteins in the circulation of live mice,” Nature Communications on Sept.1,

2021(https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-25546-y)

-ProfileProfessor Jae Myoung Suh Integrated Lab of Metabolism, Obesity and Diabetes Researchhttps://imodkaist.wixsite.com/home

Graduate School of Medical Science and Engineering College of Life Science and BioengineeringKAIST

2021.09.14 View 9717 -

3D Visualization and Quantification of Bioplastic PHA in a Living Bacterial Cell

3D holographic microscopy leads to in-depth analysis of bacterial cells accumulating the bacterial bioplastic, polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA)

A research team at KAIST has observed how bioplastic granule is being accumulated in living bacteria cells through 3D holographic microscopy. Their 3D imaging and quantitative analysis of the bioplastic ‘polyhydroxyalkanoate’ (PHA) via optical diffraction tomography provides insights into biosynthesizing sustainable substitutes for petroleum-based plastics.

The bio-degradable polyester polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) is being touted as an eco-friendly bioplastic to replace existing synthetic plastics. While carrying similar properties to general-purpose plastics such as polyethylene and polypropylene, PHA can be used in various industrial applications such as container packaging and disposable products.

PHA is synthesized by numerous bacteria as an energy and carbon storage material under unbalanced growth conditions in the presence of excess carbon sources. PHA exists in the form of insoluble granules in the cytoplasm. Previous studies on investigating in vivo PHA granules have been performed by using fluorescence microscopy, transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and electron cryotomography.

These techniques have generally relied on the statistical analysis of multiple 2D snapshots of fixed cells or the short-time monitoring of the cells. For the TEM analysis, cells need to be fixed and sectioned, and thus the investigation of living cells was not possible. Fluorescence-based techniques require fluorescence labeling or dye staining. Thus, indirect imaging with the use of reporter proteins cannot show the native state of PHAs or cells, and invasive exogenous dyes can affect the physiology and viability of the cells. Therefore, it was difficult to fully understand the formation of PHA granules in cells due to the technical limitations, and thus several mechanism models based on the observations have been only proposed.

The team of metabolic engineering researchers led by Distinguished Professor Sang Yup Lee and Physics Professor YongKeun Park, who established the startup Tomocube with his 3D holographic microscopy, reported the results of 3D quantitative label-free analysis of PHA granules in individual live bacterial cells by measuring the refractive index distributions using optical diffraction tomography. The formation and growth of PHA granules in the cells of Cupriavidus necator, the most-studied native PHA (specifically, poly(3-hydroxybutyrate), also known as PHB) producer, and recombinant Escherichia coli harboring C. necator PHB biosynthesis pathway were comparatively examined.

From the reconstructed 3D refractive index distribution of the cells, the team succeeded in the 3D visualization and quantitative analysis of cells and intracellular PHA granules at a single-cell level. In particular, the team newly presented the concept of “in vivo PHA granule density.” Through the statistical analysis of hundreds of single cells accumulating PHA granules, the distinctive differences of density and localization of PHA granules in the two micro-organisms were found. Furthermore, the team identified the key protein that plays a major role in making the difference that enabled the characteristics of PHA granules in the recombinant E. coli to become similar to those of C. necator.

The research team also presented 3D time-lapse movies showing the actual processes of PHA granule formation combined with cell growth and division. Movies showing the living cells synthesizing and accumulating PHA granules in their native state had never been reported before.

Professor Lee said, “This study provides insights into the morphological and physical characteristics of in vivo PHA as well as the unique mechanisms of PHA granule formation that undergo the phase transition from soluble monomers into the insoluble polymer, followed by granule formation. Through this study, a deeper understanding of PHA granule formation within the bacterial cells is now possible, which has great significance in that a convergence study of biology and physics was achieved. This study will help develop various bioplastics production processes in the future.”

This work was supported by the Technology Development Program to Solve Climate Changes on Systems Metabolic Engineering for Biorefineries (Grants NRF-2012M1A2A2026556 and NRF-2012M1A2A2026557) and the Bio & Medical Technology Development Program (Grant No. 2021M3A9I4022740) from the Ministry of Science and ICT (MSIT) through the National Research Foundation (NRF) of Korea to S.Y.L. This work was also supported by the KAIST Cross-Generation Collaborative Laboratory project.

-PublicationSo Young Choi, Jeonghun Oh, JaeHwang Jung, YongKeun Park, and Sang Yup Lee. Three-dimensional label-free visualization and quantification of polyhydroxyalkanoates in individualbacterial cell in its native state. PNAS(https://doi.org./10.1073/pnas.2103956118)

-ProfileDistinguished Professor Sang Yup LeeMetabolic Engineering and Synthetic Biologyhttp://mbel.kaist.ac.kr/

Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering KAIST

Endowed Chair Professor YongKeun ParkBiomedical Optics Laboratoryhttps://bmokaist.wordpress.com/

Department of PhysicsKAIST

2021.07.28 View 13940

3D Visualization and Quantification of Bioplastic PHA in a Living Bacterial Cell

3D holographic microscopy leads to in-depth analysis of bacterial cells accumulating the bacterial bioplastic, polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA)

A research team at KAIST has observed how bioplastic granule is being accumulated in living bacteria cells through 3D holographic microscopy. Their 3D imaging and quantitative analysis of the bioplastic ‘polyhydroxyalkanoate’ (PHA) via optical diffraction tomography provides insights into biosynthesizing sustainable substitutes for petroleum-based plastics.

The bio-degradable polyester polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) is being touted as an eco-friendly bioplastic to replace existing synthetic plastics. While carrying similar properties to general-purpose plastics such as polyethylene and polypropylene, PHA can be used in various industrial applications such as container packaging and disposable products.

PHA is synthesized by numerous bacteria as an energy and carbon storage material under unbalanced growth conditions in the presence of excess carbon sources. PHA exists in the form of insoluble granules in the cytoplasm. Previous studies on investigating in vivo PHA granules have been performed by using fluorescence microscopy, transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and electron cryotomography.

These techniques have generally relied on the statistical analysis of multiple 2D snapshots of fixed cells or the short-time monitoring of the cells. For the TEM analysis, cells need to be fixed and sectioned, and thus the investigation of living cells was not possible. Fluorescence-based techniques require fluorescence labeling or dye staining. Thus, indirect imaging with the use of reporter proteins cannot show the native state of PHAs or cells, and invasive exogenous dyes can affect the physiology and viability of the cells. Therefore, it was difficult to fully understand the formation of PHA granules in cells due to the technical limitations, and thus several mechanism models based on the observations have been only proposed.

The team of metabolic engineering researchers led by Distinguished Professor Sang Yup Lee and Physics Professor YongKeun Park, who established the startup Tomocube with his 3D holographic microscopy, reported the results of 3D quantitative label-free analysis of PHA granules in individual live bacterial cells by measuring the refractive index distributions using optical diffraction tomography. The formation and growth of PHA granules in the cells of Cupriavidus necator, the most-studied native PHA (specifically, poly(3-hydroxybutyrate), also known as PHB) producer, and recombinant Escherichia coli harboring C. necator PHB biosynthesis pathway were comparatively examined.

From the reconstructed 3D refractive index distribution of the cells, the team succeeded in the 3D visualization and quantitative analysis of cells and intracellular PHA granules at a single-cell level. In particular, the team newly presented the concept of “in vivo PHA granule density.” Through the statistical analysis of hundreds of single cells accumulating PHA granules, the distinctive differences of density and localization of PHA granules in the two micro-organisms were found. Furthermore, the team identified the key protein that plays a major role in making the difference that enabled the characteristics of PHA granules in the recombinant E. coli to become similar to those of C. necator.

The research team also presented 3D time-lapse movies showing the actual processes of PHA granule formation combined with cell growth and division. Movies showing the living cells synthesizing and accumulating PHA granules in their native state had never been reported before.

Professor Lee said, “This study provides insights into the morphological and physical characteristics of in vivo PHA as well as the unique mechanisms of PHA granule formation that undergo the phase transition from soluble monomers into the insoluble polymer, followed by granule formation. Through this study, a deeper understanding of PHA granule formation within the bacterial cells is now possible, which has great significance in that a convergence study of biology and physics was achieved. This study will help develop various bioplastics production processes in the future.”

This work was supported by the Technology Development Program to Solve Climate Changes on Systems Metabolic Engineering for Biorefineries (Grants NRF-2012M1A2A2026556 and NRF-2012M1A2A2026557) and the Bio & Medical Technology Development Program (Grant No. 2021M3A9I4022740) from the Ministry of Science and ICT (MSIT) through the National Research Foundation (NRF) of Korea to S.Y.L. This work was also supported by the KAIST Cross-Generation Collaborative Laboratory project.

-PublicationSo Young Choi, Jeonghun Oh, JaeHwang Jung, YongKeun Park, and Sang Yup Lee. Three-dimensional label-free visualization and quantification of polyhydroxyalkanoates in individualbacterial cell in its native state. PNAS(https://doi.org./10.1073/pnas.2103956118)

-ProfileDistinguished Professor Sang Yup LeeMetabolic Engineering and Synthetic Biologyhttp://mbel.kaist.ac.kr/

Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering KAIST

Endowed Chair Professor YongKeun ParkBiomedical Optics Laboratoryhttps://bmokaist.wordpress.com/

Department of PhysicsKAIST

2021.07.28 View 13940 -

Professor Jae Kyoung Kim to Lead a New Mathematical Biology Research Group at IBS

Professor Jae Kyoung Kim from the KAIST Department of Mathematical Sciences was appointed as the third Chief Investigator (CI) of the Pioneer Research Center (PRC) for Mathematical and Computational Sciences at the Institute for Basic Science (IBS). Professor Kim will launch and lead a new research group that will be devoted to resolving various biological conundrums from a mathematical perspective. His appointment began on March 1, 2021.

Professor Kim, a rising researcher in the field of mathematical biology, has received attention from both the mathematical and biological communities at the international level. Professor Kim puts novel and unremitting efforts into understanding biological systems such as cell-to-cell interactions mathematically and designing mathematical models for identifying causes of diseases and developing therapeutic medicines.

Through active joint research with biologists, mathematician Kim has addressed many challenges that have remained unsolved in biology and published papers in a number of leading international journals in related fields. His notable works based on mathematical modelling include having designed a biological circuit that can maintain a stable circadian rhythm (Science, 2015) and unveiling the principles of how the biological clock in the body maintains a steady speed for the first time in over 60 years (Molecular Cell, 2015). Recently, through a joint research project with Pfizer, Professor Kim identified what causes the differences between animal and clinical test results during drug development explaining why drugs have different efficacies in different people (Molecular Systems Biology, 2019).

The new IBS biomedical mathematics research group led by Professor Kim will further investigate the causes of unstable circadian rhythms and sleeping patterns. The team will aim to present a new paradigm in treatments for sleep disorders.

Professor Kim said, “We are all so familiar with sleep behaviors, but the exact mechanisms behind how such behaviors occur are still unknown. Through cooperation with biomedical scientists, our group will do its best to discover the complicated, fundamental mechanisms of sleep, and investigate the causes and cures of sleep disorders.”

Every year, the IBS selects young and promising researchers and appoints them as CIs. A maximum of five selected CIs can form each independent research group within the IBS PRC, and receive research funds of 1 billion to 1.5 billion KRW over five years.

(END)

2021.03.18 View 10391

Professor Jae Kyoung Kim to Lead a New Mathematical Biology Research Group at IBS

Professor Jae Kyoung Kim from the KAIST Department of Mathematical Sciences was appointed as the third Chief Investigator (CI) of the Pioneer Research Center (PRC) for Mathematical and Computational Sciences at the Institute for Basic Science (IBS). Professor Kim will launch and lead a new research group that will be devoted to resolving various biological conundrums from a mathematical perspective. His appointment began on March 1, 2021.

Professor Kim, a rising researcher in the field of mathematical biology, has received attention from both the mathematical and biological communities at the international level. Professor Kim puts novel and unremitting efforts into understanding biological systems such as cell-to-cell interactions mathematically and designing mathematical models for identifying causes of diseases and developing therapeutic medicines.

Through active joint research with biologists, mathematician Kim has addressed many challenges that have remained unsolved in biology and published papers in a number of leading international journals in related fields. His notable works based on mathematical modelling include having designed a biological circuit that can maintain a stable circadian rhythm (Science, 2015) and unveiling the principles of how the biological clock in the body maintains a steady speed for the first time in over 60 years (Molecular Cell, 2015). Recently, through a joint research project with Pfizer, Professor Kim identified what causes the differences between animal and clinical test results during drug development explaining why drugs have different efficacies in different people (Molecular Systems Biology, 2019).

The new IBS biomedical mathematics research group led by Professor Kim will further investigate the causes of unstable circadian rhythms and sleeping patterns. The team will aim to present a new paradigm in treatments for sleep disorders.

Professor Kim said, “We are all so familiar with sleep behaviors, but the exact mechanisms behind how such behaviors occur are still unknown. Through cooperation with biomedical scientists, our group will do its best to discover the complicated, fundamental mechanisms of sleep, and investigate the causes and cures of sleep disorders.”

Every year, the IBS selects young and promising researchers and appoints them as CIs. A maximum of five selected CIs can form each independent research group within the IBS PRC, and receive research funds of 1 billion to 1.5 billion KRW over five years.

(END)

2021.03.18 View 10391 -

E. coli Engineered to Grow on CO₂ and Formic Acid as Sole Carbon Sources

- An E. coli strain that can grow to a relatively high cell density solely on CO₂ and formic acid was developed by employing metabolic engineering. -

Most biorefinery processes have relied on the use of biomass as a raw material for the production of chemicals and materials. Even though the use of CO₂ as a carbon source in biorefineries is desirable, it has not been possible to make common microbial strains such as E. coli grow on CO₂.

Now, a metabolic engineering research group at KAIST has developed a strategy to grow an E. coli strain to higher cell density solely on CO₂ and formic acid. Formic acid is a one carbon carboxylic acid, and can be easily produced from CO₂ using a variety of methods. Since it is easier to store and transport than CO₂, formic acid can be considered a good liquid-form alternative of CO₂.

With support from the C1 Gas Refinery R&D Center and the Ministry of Science and ICT, a research team led by Distinguished Professor Sang Yup Lee stepped up their work to develop an engineered E. coli strain capable of growing up to 11-fold higher cell density than those previously reported, using CO₂ and formic acid as sole carbon sources. This work was published in Nature Microbiology on September 28.

Despite the recent reports by several research groups on the development of E. coli strains capable of growing on CO₂ and formic acid, the maximum cell growth remained too low (optical density of around 1) and thus the production of chemicals from CO₂ and formic acid has been far from realized.

The team previously reported the reconstruction of the tetrahydrofolate cycle and reverse glycine cleavage pathway to construct an engineered E. coli strain that can sustain growth on CO₂ and formic acid. To further enhance the growth, the research team introduced the previously designed synthetic CO₂ and formic acid assimilation pathway, and two formate dehydrogenases.

Metabolic fluxes were also fine-tuned, the gluconeogenic flux enhanced, and the levels of cytochrome bo3 and bd-I ubiquinol oxidase for ATP generation were optimized. This engineered E. coli strain was able to grow to a relatively high OD600 of 7~11, showing promise as a platform strain growing solely on CO₂ and formic acid.

Professor Lee said, “We engineered E. coli that can grow to a higher cell density only using CO₂ and formic acid. We think that this is an important step forward, but this is not the end. The engineered strain we developed still needs further engineering so that it can grow faster to a much higher density.”

Professor Lee’s team is continuing to develop such a strain. “In the future, we would be delighted to see the production of chemicals from an engineered E. coli strain using CO₂ and formic acid as sole carbon sources,” he added.

-Profile:Distinguished Professor Sang Yup Leehttp://mbel.kaist.ac.krDepartment of Chemical and Biomolecular EngineeringKAIST

2020.09.29 View 11858

E. coli Engineered to Grow on CO₂ and Formic Acid as Sole Carbon Sources

- An E. coli strain that can grow to a relatively high cell density solely on CO₂ and formic acid was developed by employing metabolic engineering. -

Most biorefinery processes have relied on the use of biomass as a raw material for the production of chemicals and materials. Even though the use of CO₂ as a carbon source in biorefineries is desirable, it has not been possible to make common microbial strains such as E. coli grow on CO₂.

Now, a metabolic engineering research group at KAIST has developed a strategy to grow an E. coli strain to higher cell density solely on CO₂ and formic acid. Formic acid is a one carbon carboxylic acid, and can be easily produced from CO₂ using a variety of methods. Since it is easier to store and transport than CO₂, formic acid can be considered a good liquid-form alternative of CO₂.

With support from the C1 Gas Refinery R&D Center and the Ministry of Science and ICT, a research team led by Distinguished Professor Sang Yup Lee stepped up their work to develop an engineered E. coli strain capable of growing up to 11-fold higher cell density than those previously reported, using CO₂ and formic acid as sole carbon sources. This work was published in Nature Microbiology on September 28.

Despite the recent reports by several research groups on the development of E. coli strains capable of growing on CO₂ and formic acid, the maximum cell growth remained too low (optical density of around 1) and thus the production of chemicals from CO₂ and formic acid has been far from realized.

The team previously reported the reconstruction of the tetrahydrofolate cycle and reverse glycine cleavage pathway to construct an engineered E. coli strain that can sustain growth on CO₂ and formic acid. To further enhance the growth, the research team introduced the previously designed synthetic CO₂ and formic acid assimilation pathway, and two formate dehydrogenases.

Metabolic fluxes were also fine-tuned, the gluconeogenic flux enhanced, and the levels of cytochrome bo3 and bd-I ubiquinol oxidase for ATP generation were optimized. This engineered E. coli strain was able to grow to a relatively high OD600 of 7~11, showing promise as a platform strain growing solely on CO₂ and formic acid.

Professor Lee said, “We engineered E. coli that can grow to a higher cell density only using CO₂ and formic acid. We think that this is an important step forward, but this is not the end. The engineered strain we developed still needs further engineering so that it can grow faster to a much higher density.”

Professor Lee’s team is continuing to develop such a strain. “In the future, we would be delighted to see the production of chemicals from an engineered E. coli strain using CO₂ and formic acid as sole carbon sources,” he added.

-Profile:Distinguished Professor Sang Yup Leehttp://mbel.kaist.ac.krDepartment of Chemical and Biomolecular EngineeringKAIST

2020.09.29 View 11858 -

Universal Virus Detection Platform to Expedite Viral Diagnosis

Reactive polymer-based tester pre-screens dsRNAs of a wide range of viruses without their genome sequences

The prompt, precise, and massive detection of a virus is the key to combat infectious diseases such as Covid-19. A new viral diagnostic strategy using reactive polymer-grafted, double-stranded RNAs will serve as a pre-screening tester for a wide range of viruses with enhanced sensitivity.

Currently, the most widely using viral detection methodology is polymerase chain reaction (PCR) diagnosis, which amplifies and detects a piece of the viral genome. Prior knowledge of the relevant primer nucleic acids of the virus is quintessential for this test.

The detection platform developed by KAIST researchers identifies viral activities without amplifying specific nucleic acid targets. The research team, co-led by Professor Sheng Li and Professor Yoosik Kim from the Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, constructed a universal virus detection platform by utilizing the distinct features of the PPFPA-grafted surface and double-stranded RNAs.

The key principle of this platform is utilizing the distinct feature of reactive polymer-grafted surfaces, which serve as a versatile platform for the immobilization of functional molecules. These activated surfaces can be used in a wide range of applications including separation, delivery, and detection. As long double-stranded RNAs are common byproducts of viral transcription and replication, these PPFPA-grafted surfaces can detect the presence of different kinds of viruses without prior knowledge of their genomic sequences.

“We employed the PPFPA-grafted silicon surface to develop a universal virus detection platform by immobilizing antibodies that recognize double-stranded RNAs,” said Professor Kim.

To increase detection sensitivity, the research team devised two-step detection process analogues to sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay where the bound double-stranded RNAs are then visualized using fluorophore-tagged antibodies that also recognize the RNAs’ double-stranded secondary structure.

By utilizing the developed platform, long double-stranded RNAs can be detected and visualized from an RNA mixture as well as from total cell lysates, which contain a mixture of various abundant contaminants such as DNAs and proteins.

The research team successfully detected elevated levels of hepatitis C and A viruses with this tool.

“This new technology allows us to take on virus detection from a new perspective. By targeting a common biomarker, viral double-stranded RNAs, we can develop a pre-screening platform that can quickly differentiate infected populations from non-infected ones,” said Professor Li.

“This detection platform provides new perspectives for diagnosing infectious diseases. This will provide fast and accurate diagnoses for an infected population and prevent the influx of massive outbreaks,” said Professor Kim.

This work is featured in Biomacromolecules. This work was supported by the Agency for Defense Development (Grant UD170039ID), the Ministry of Science and ICT (NRF-2017R1D1A1B03034660, NRF-2019R1C1C1006672), and the KAIST Future Systems Healthcare Project from the Ministry of Science and ICT (KAISTHEALTHCARE42).

Profile:-Professor Yoosik KimDepartment of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineeringhttps://qcbio.kaist.ac.kr

KAIST-Professor Sheng LiDepartment of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineeringhttps://bcpolymer.kaist.ac.kr

KAIST

Publication:Ku et al., 2020. Reactive Polymer Targeting dsRNA as Universal Virus Detection Platform with Enhanced Sensitivity. Biomacromolecules (https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.biomac.0c00379).

2020.06.01 View 19471

Universal Virus Detection Platform to Expedite Viral Diagnosis

Reactive polymer-based tester pre-screens dsRNAs of a wide range of viruses without their genome sequences

The prompt, precise, and massive detection of a virus is the key to combat infectious diseases such as Covid-19. A new viral diagnostic strategy using reactive polymer-grafted, double-stranded RNAs will serve as a pre-screening tester for a wide range of viruses with enhanced sensitivity.

Currently, the most widely using viral detection methodology is polymerase chain reaction (PCR) diagnosis, which amplifies and detects a piece of the viral genome. Prior knowledge of the relevant primer nucleic acids of the virus is quintessential for this test.

The detection platform developed by KAIST researchers identifies viral activities without amplifying specific nucleic acid targets. The research team, co-led by Professor Sheng Li and Professor Yoosik Kim from the Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, constructed a universal virus detection platform by utilizing the distinct features of the PPFPA-grafted surface and double-stranded RNAs.

The key principle of this platform is utilizing the distinct feature of reactive polymer-grafted surfaces, which serve as a versatile platform for the immobilization of functional molecules. These activated surfaces can be used in a wide range of applications including separation, delivery, and detection. As long double-stranded RNAs are common byproducts of viral transcription and replication, these PPFPA-grafted surfaces can detect the presence of different kinds of viruses without prior knowledge of their genomic sequences.

“We employed the PPFPA-grafted silicon surface to develop a universal virus detection platform by immobilizing antibodies that recognize double-stranded RNAs,” said Professor Kim.

To increase detection sensitivity, the research team devised two-step detection process analogues to sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay where the bound double-stranded RNAs are then visualized using fluorophore-tagged antibodies that also recognize the RNAs’ double-stranded secondary structure.

By utilizing the developed platform, long double-stranded RNAs can be detected and visualized from an RNA mixture as well as from total cell lysates, which contain a mixture of various abundant contaminants such as DNAs and proteins.

The research team successfully detected elevated levels of hepatitis C and A viruses with this tool.

“This new technology allows us to take on virus detection from a new perspective. By targeting a common biomarker, viral double-stranded RNAs, we can develop a pre-screening platform that can quickly differentiate infected populations from non-infected ones,” said Professor Li.

“This detection platform provides new perspectives for diagnosing infectious diseases. This will provide fast and accurate diagnoses for an infected population and prevent the influx of massive outbreaks,” said Professor Kim.

This work is featured in Biomacromolecules. This work was supported by the Agency for Defense Development (Grant UD170039ID), the Ministry of Science and ICT (NRF-2017R1D1A1B03034660, NRF-2019R1C1C1006672), and the KAIST Future Systems Healthcare Project from the Ministry of Science and ICT (KAISTHEALTHCARE42).

Profile:-Professor Yoosik KimDepartment of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineeringhttps://qcbio.kaist.ac.kr

KAIST-Professor Sheng LiDepartment of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineeringhttps://bcpolymer.kaist.ac.kr

KAIST

Publication:Ku et al., 2020. Reactive Polymer Targeting dsRNA as Universal Virus Detection Platform with Enhanced Sensitivity. Biomacromolecules (https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.biomac.0c00379).

2020.06.01 View 19471 -

A Single Biological Factor Predicts Distinct Cortical Organizations across Mammalian Species

-A KAIST team’s mathematical sampling model shows that retino-cortical mapping is a prime determinant in the topography of cortical organization.-

Researchers have explained how visual cortexes develop uniquely across the brains of different mammalian species. A KAIST research team led by Professor Se-Bum Paik from the Department of Bio and Brain Engineering has identified a single biological factor, the retino-cortical mapping ratio, that predicts distinct cortical organizations across mammalian species.

This new finding has resolved a long-standing puzzle in understanding visual neuroscience regarding the origin of functional architectures in the visual cortex. The study published in Cell Reports on March 10 demonstrates that the evolutionary variation of biological parameters may induce the development of distinct functional circuits in the visual cortex, even without species-specific developmental mechanisms.

In the primary visual cortex (V1) of mammals, neural tuning to visual stimulus orientation is organized into one of two distinct topographic patterns across species. While primates have columnar orientation maps, a salt-and-pepper type organization is observed in rodents.

For decades, this sharp contrast between cortical organizations has spawned fundamental questions about the origin of functional architectures in the V1. However, it remained unknown whether these patterns reflect disparate developmental mechanisms across mammalian taxa, or simply originate from variations in biological parameters under a universal development process.

To identify a determinant predicting distinct cortical organizations, Professor Paik and his researchers Jaeson Jang and Min Song examined the exact condition that generates columnar and salt-and-pepper organizations, respectively. Next, they applied a mathematical model to investigate how the topographic information of the underlying retinal mosaics pattern could be differently mapped onto a cortical space, depending on the mapping condition.

The research team proved that the retino-cortical feedforwarding mapping ratio appeared to be correlated to the cortical organization of each species. In the model simulations, the team found that distinct cortical circuitries can arise from different V1 areas and retinal ganglion cell (RGC) mosaic sizes. The team’s mathematical sampling model shows that retino-cortical mapping is a prime determinant in the topography of cortical organization, and this prediction was confirmed by neural parameter analysis of the data from eight phylogenetically distinct mammalian species.

Furthermore, the researchers proved that the Nyquist sampling theorem explains this parametric division of cortical organization with high accuracy. They showed that a mathematical model predicts that the organization of cortical orientation tuning makes a sharp transition around the Nyquist sampling frequency, explaining why cortical organizations can be observed in either columnar or salt-and-pepper organizations, but not in intermediates between these two stages.

Professor Paik said, “Our findings make a significant impact for understanding the origin of functional architectures in the visual cortex of the brain, and will provide a broad conceptual advancement as well as advanced insights into the mechanism underlying neural development in evolutionarily divergent species.”

He continued, “We believe that our findings will be of great interest to scientists working in a wide range of fields such as neuroscience, vision science, and developmental biology.”

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF).

Image credit: Professor Se-Bum Paik, KAIST

Image usage restrictions: News organizations may use or redistribute this image, with proper attribution, as part of news coverage of this paper only.

Publication:

Jaeson Jang, Min Song, and Se-Bum Paik. (2020). Retino-cortical mapping ratio predicts columnar and salt-and-pepper organization in mammalian visual cortex. Cell Reports. Volume 30. Issue 10. pp. 3270-3279. Available online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2020.02.038

Profile:

Se-Bum Paik

Assistant Professor

sbpaik@kaist.ac.kr

http://vs.kaist.ac.kr/

VSNN Laboratory

Department of Bio and Brain Engineering

Program of Brain and Cognitive Engineering

http://kaist.ac.kr

Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST)

Daejeon, Republic of Korea

Profile:

Jaeson Jang

Ph.D. Candidate

jaesonjang@kaist.ac.kr

Department of Bio and Brain Engineering, KAIST

Profile:

Min Song

Ph.D. Candidate

night@kaist.ac.kr

Program of Brain and Cognitive Engineering, KAIST

(END)

2020.03.11 View 14664

A Single Biological Factor Predicts Distinct Cortical Organizations across Mammalian Species

-A KAIST team’s mathematical sampling model shows that retino-cortical mapping is a prime determinant in the topography of cortical organization.-

Researchers have explained how visual cortexes develop uniquely across the brains of different mammalian species. A KAIST research team led by Professor Se-Bum Paik from the Department of Bio and Brain Engineering has identified a single biological factor, the retino-cortical mapping ratio, that predicts distinct cortical organizations across mammalian species.

This new finding has resolved a long-standing puzzle in understanding visual neuroscience regarding the origin of functional architectures in the visual cortex. The study published in Cell Reports on March 10 demonstrates that the evolutionary variation of biological parameters may induce the development of distinct functional circuits in the visual cortex, even without species-specific developmental mechanisms.

In the primary visual cortex (V1) of mammals, neural tuning to visual stimulus orientation is organized into one of two distinct topographic patterns across species. While primates have columnar orientation maps, a salt-and-pepper type organization is observed in rodents.

For decades, this sharp contrast between cortical organizations has spawned fundamental questions about the origin of functional architectures in the V1. However, it remained unknown whether these patterns reflect disparate developmental mechanisms across mammalian taxa, or simply originate from variations in biological parameters under a universal development process.

To identify a determinant predicting distinct cortical organizations, Professor Paik and his researchers Jaeson Jang and Min Song examined the exact condition that generates columnar and salt-and-pepper organizations, respectively. Next, they applied a mathematical model to investigate how the topographic information of the underlying retinal mosaics pattern could be differently mapped onto a cortical space, depending on the mapping condition.

The research team proved that the retino-cortical feedforwarding mapping ratio appeared to be correlated to the cortical organization of each species. In the model simulations, the team found that distinct cortical circuitries can arise from different V1 areas and retinal ganglion cell (RGC) mosaic sizes. The team’s mathematical sampling model shows that retino-cortical mapping is a prime determinant in the topography of cortical organization, and this prediction was confirmed by neural parameter analysis of the data from eight phylogenetically distinct mammalian species.

Furthermore, the researchers proved that the Nyquist sampling theorem explains this parametric division of cortical organization with high accuracy. They showed that a mathematical model predicts that the organization of cortical orientation tuning makes a sharp transition around the Nyquist sampling frequency, explaining why cortical organizations can be observed in either columnar or salt-and-pepper organizations, but not in intermediates between these two stages.

Professor Paik said, “Our findings make a significant impact for understanding the origin of functional architectures in the visual cortex of the brain, and will provide a broad conceptual advancement as well as advanced insights into the mechanism underlying neural development in evolutionarily divergent species.”

He continued, “We believe that our findings will be of great interest to scientists working in a wide range of fields such as neuroscience, vision science, and developmental biology.”

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF).

Image credit: Professor Se-Bum Paik, KAIST

Image usage restrictions: News organizations may use or redistribute this image, with proper attribution, as part of news coverage of this paper only.

Publication:

Jaeson Jang, Min Song, and Se-Bum Paik. (2020). Retino-cortical mapping ratio predicts columnar and salt-and-pepper organization in mammalian visual cortex. Cell Reports. Volume 30. Issue 10. pp. 3270-3279. Available online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2020.02.038

Profile:

Se-Bum Paik

Assistant Professor

sbpaik@kaist.ac.kr

http://vs.kaist.ac.kr/

VSNN Laboratory

Department of Bio and Brain Engineering

Program of Brain and Cognitive Engineering

http://kaist.ac.kr

Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST)

Daejeon, Republic of Korea

Profile:

Jaeson Jang

Ph.D. Candidate

jaesonjang@kaist.ac.kr

Department of Bio and Brain Engineering, KAIST

Profile:

Min Song

Ph.D. Candidate

night@kaist.ac.kr

Program of Brain and Cognitive Engineering, KAIST

(END)

2020.03.11 View 14664 -

Professor Jong Chul Ye Appointed as Distinguished Lecturer of IEEE EMBS

Professor Jong Chul Ye from the Department of Bio and Brain Engineering was appointed as a distinguished lecturer by the International Association of Electrical and Electronic Engineers (IEEE) Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBS). Professor Ye was invited to deliver a lecture on his leading research on artificial intelligence (AI) technology in medical video restoration. He will serve a term of two years beginning in 2020.

IEEE EMBS's distinguished lecturer program is designed to educate researchers around the world on the latest trends and technology in biomedical engineering. Sponsored by IEEE, its members can attend lectures on the distinguished professor's research subject.

Professor Ye said, "We are at a time where the importance of AI in medical imaging is increasing.” He added, “I am proud to be appointed as a distinguished lecturer of the IEEE EMBS in recognition of my contributions to this field.”

(END)

2020.02.27 View 11519

Professor Jong Chul Ye Appointed as Distinguished Lecturer of IEEE EMBS

Professor Jong Chul Ye from the Department of Bio and Brain Engineering was appointed as a distinguished lecturer by the International Association of Electrical and Electronic Engineers (IEEE) Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBS). Professor Ye was invited to deliver a lecture on his leading research on artificial intelligence (AI) technology in medical video restoration. He will serve a term of two years beginning in 2020.

IEEE EMBS's distinguished lecturer program is designed to educate researchers around the world on the latest trends and technology in biomedical engineering. Sponsored by IEEE, its members can attend lectures on the distinguished professor's research subject.

Professor Ye said, "We are at a time where the importance of AI in medical imaging is increasing.” He added, “I am proud to be appointed as a distinguished lecturer of the IEEE EMBS in recognition of my contributions to this field.”

(END)

2020.02.27 View 11519 -

Scientists Discover the Mechanism of DNA High-Order Structure Formation

(Molecular structures of Abo1 in different energy states (left), Demonstration of an Abo1-assisted histone loading onto DNA by the DNA curtain assay. )

The genetic material of our cells—DNA—exists in a high-order structure called “chromatin”. Chromatin consists of DNA wrapped around histone proteins and efficiently packs DNA into a small volume. Moreover, using a spool and thread analogy, chromatin allows DNA to be locally wound or unwound, thus enabling genes to be enclosed or exposed. The misregulation of chromatin structures results in aberrant gene expression and can ultimately lead to developmental disorders or cancers. Despite the importance of DNA high-order structures, the complexity of the underlying machinery has circumvented molecular dissection.

For the first time, molecular biologists have uncovered how one particular mechanism uses energy to ensure proper histone placement onto DNA to form chromatin. They published their results on Dec. 17 in Nature Communications.

The study focused on proteins called histone chaperones. Histone chaperones are responsible for adding and removing specific histones at specific times during the DNA packaging process. The wrong histone at the wrong time and place could result in the misregulation of gene expression or aberrant DNA replication. Thus, histone chaperones are key players in the assembly and disassembly of chromatin.

“In order to carefully control the assembly and disassembly of chromatin units, histone chaperones act as molecular escorts that prevent histone aggregation and undesired interactions,” said Professor Ji-Joon Song in the Department of Biological Sciences at KAIST. “We set out to understand how a unique histone chaperone uses chemical energy to assemble or disassemble chromatin.”

Song and his team looked to Abo1, the only known histone chaperone that utilizes cellular energy (ATP). While Abo1 is found in yeast, it has an analogous partner in other organisms, including humans, called ATAD2. Both use ATP, which is produced through a cellular process where enzymes break down a molecule’s phosphate bond. ATP energy is typically used to power other cellular processes, but it is a rare partner for histone chaperones.

“This was an interesting problem in the field because all other histone chaperones studied to date do not use ATP,” Song said.

By imaging Abo1 with a single-molecule fluorescence imaging technique known as the DNA curtain assay, the researchers could examine the protein interactions at the single-molecule level. The technique allows scientists to arrange the DNA molecules and proteins on a single layer of a microfluidic chamber and examine the layer with fluorescence microscopy.

The researchers found through real-time observation that Abo1 is ring-shaped and changes its structure to accommodate a specific histone and deposit it on DNA. Moreover, they found that the accommodating structural changes are powered by ADP.

“We discovered a mechanism by which Abo1 accommodates histone substrates, ultimately allowing it to function as a unique energy-dependent histone chaperone,” Song said. “We also found that despite looking like a protein disassembly machine, Abo1 actually loads histone substrates onto DNA to facilitate chromatin assembly.”

The researchers plan to continue exploring how energy-dependent histone chaperones bind and release histones, with the ultimate goal of developing therapeutics that can target cancer-causing misbehavior by Abo1’s analogous human counterpart, ATAD2.

-Profile

Professor Ji-Joon Song

Department of Biological Sciences KI for the BioCentury (https://kis.kaist.ac.kr/index.php?mid=KIB_O) KAIST

2020.01.07 View 11031

Scientists Discover the Mechanism of DNA High-Order Structure Formation

(Molecular structures of Abo1 in different energy states (left), Demonstration of an Abo1-assisted histone loading onto DNA by the DNA curtain assay. )

The genetic material of our cells—DNA—exists in a high-order structure called “chromatin”. Chromatin consists of DNA wrapped around histone proteins and efficiently packs DNA into a small volume. Moreover, using a spool and thread analogy, chromatin allows DNA to be locally wound or unwound, thus enabling genes to be enclosed or exposed. The misregulation of chromatin structures results in aberrant gene expression and can ultimately lead to developmental disorders or cancers. Despite the importance of DNA high-order structures, the complexity of the underlying machinery has circumvented molecular dissection.

For the first time, molecular biologists have uncovered how one particular mechanism uses energy to ensure proper histone placement onto DNA to form chromatin. They published their results on Dec. 17 in Nature Communications.

The study focused on proteins called histone chaperones. Histone chaperones are responsible for adding and removing specific histones at specific times during the DNA packaging process. The wrong histone at the wrong time and place could result in the misregulation of gene expression or aberrant DNA replication. Thus, histone chaperones are key players in the assembly and disassembly of chromatin.

“In order to carefully control the assembly and disassembly of chromatin units, histone chaperones act as molecular escorts that prevent histone aggregation and undesired interactions,” said Professor Ji-Joon Song in the Department of Biological Sciences at KAIST. “We set out to understand how a unique histone chaperone uses chemical energy to assemble or disassemble chromatin.”

Song and his team looked to Abo1, the only known histone chaperone that utilizes cellular energy (ATP). While Abo1 is found in yeast, it has an analogous partner in other organisms, including humans, called ATAD2. Both use ATP, which is produced through a cellular process where enzymes break down a molecule’s phosphate bond. ATP energy is typically used to power other cellular processes, but it is a rare partner for histone chaperones.

“This was an interesting problem in the field because all other histone chaperones studied to date do not use ATP,” Song said.

By imaging Abo1 with a single-molecule fluorescence imaging technique known as the DNA curtain assay, the researchers could examine the protein interactions at the single-molecule level. The technique allows scientists to arrange the DNA molecules and proteins on a single layer of a microfluidic chamber and examine the layer with fluorescence microscopy.

The researchers found through real-time observation that Abo1 is ring-shaped and changes its structure to accommodate a specific histone and deposit it on DNA. Moreover, they found that the accommodating structural changes are powered by ADP.

“We discovered a mechanism by which Abo1 accommodates histone substrates, ultimately allowing it to function as a unique energy-dependent histone chaperone,” Song said. “We also found that despite looking like a protein disassembly machine, Abo1 actually loads histone substrates onto DNA to facilitate chromatin assembly.”

The researchers plan to continue exploring how energy-dependent histone chaperones bind and release histones, with the ultimate goal of developing therapeutics that can target cancer-causing misbehavior by Abo1’s analogous human counterpart, ATAD2.

-Profile

Professor Ji-Joon Song

Department of Biological Sciences KI for the BioCentury (https://kis.kaist.ac.kr/index.php?mid=KIB_O) KAIST

2020.01.07 View 11031 -

A Single, Master Switch for Sugar Levels?

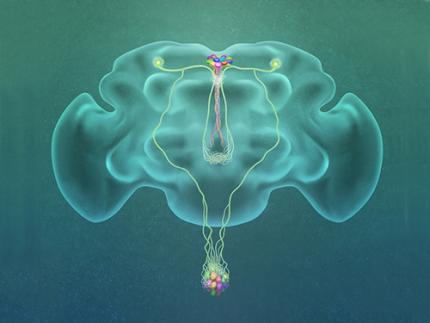

When a fly eats sugar, a single brain cell sends simultaneous messages to stimulate one hormone and inhibit another to control glucose levels in the body. Further research into this control system with remarkable precision could shed light on the neural mechanisms of diabetes and obesity in humans .

A single neuron appears to monitor and control sugar levels in the fly body, according to research published this week in Nature. This new insight into the mechanisms in the fly brain that maintain a balance of two key hormones controlling glucose levels, insulin and glucagon, can provide a framework for understanding diabetes and obesity in humans.

Neurons that sense and respond to glucose were identified more than 50 years ago, but what they do in our body has remained unclear. Researchers at the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST) and New York University School of Medicine have now found a single “glucose-sensing neuron” that appears to be the master controller in Drosophila, the vinegar fly, for maintaining an ideal glucose balance, called homeostasis.

Professor Greg Seong-Bae Suh, Dr. Yangkyun Oh and colleagues identified a key neuron that is excited by glucose, which they called CN neuron. This CN neuron has a unique shape – it has an axon (which is used to transmit information to downstream cells) that is bifurcated. One branch projects to insulin-producing cells, and sends a signal triggering the secretion of the insulin equivalent in flies. The other branch projects to glucagon-producing cells and sends a signal inhibiting the secretion of the glucagon equivalent.

When flies consume food, the levels of glucose in their body increase; this excites the CN neuron, which fires the simultaneous signals to stimulate insulin and inhibit glucagon secretion, thereby maintaining the appropriate balance between the hormones and sugar in the blood. The researchers were able to see this happening in the brain in real time by using a combination of cutting-edge fluorescent calcium imaging technology, as well as measuring hormone and sugar levels and applying highly sophisticated molecular genetic techniques.

When flies were not fed, however, the researchers observed a reduction in the activity of CN neuron, a reduction in insulin secretion and an increase in glucagon secretion. These findings indicate that these key hormones are under the direct control of the glucose-sensing neuron. Furthermore, when they silenced the CN neuron rendering dysfunctional CN neuron in flies, these animals experienced an imbalance, resulting in hyperglycemia – high levels of sugars in the blood, similar to what is observed in diabetes in humans. This further suggests that the CN neuron is critical to maintaining glucose homeostasis in animals.

While further research is required to investigate this process in humans, Suh notes this is a significant step forward in the fields of both neurobiology and endocrinology.

“This work lays the foundation for translational research to better understand how this delicate regulatory process is affected by diabetes, obesity, excessive nutrition and diets high in sugar,” Suh said.

Profile: Greg Seong-Bae Suh

seongbaesuh@kaist.ac.kr

Professor Department of Biological Sciences

KAIST

(Figure: A single glucose-excited CN neuron extends bifurcated axonal branches,

one of which innervates insulin producing cells and stimulates their activity an the other axonal branch projects to glucagon producing cells and inhibits their activity.)

2019.10.24 View 18093

A Single, Master Switch for Sugar Levels?

When a fly eats sugar, a single brain cell sends simultaneous messages to stimulate one hormone and inhibit another to control glucose levels in the body. Further research into this control system with remarkable precision could shed light on the neural mechanisms of diabetes and obesity in humans .

A single neuron appears to monitor and control sugar levels in the fly body, according to research published this week in Nature. This new insight into the mechanisms in the fly brain that maintain a balance of two key hormones controlling glucose levels, insulin and glucagon, can provide a framework for understanding diabetes and obesity in humans.

Neurons that sense and respond to glucose were identified more than 50 years ago, but what they do in our body has remained unclear. Researchers at the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST) and New York University School of Medicine have now found a single “glucose-sensing neuron” that appears to be the master controller in Drosophila, the vinegar fly, for maintaining an ideal glucose balance, called homeostasis.

Professor Greg Seong-Bae Suh, Dr. Yangkyun Oh and colleagues identified a key neuron that is excited by glucose, which they called CN neuron. This CN neuron has a unique shape – it has an axon (which is used to transmit information to downstream cells) that is bifurcated. One branch projects to insulin-producing cells, and sends a signal triggering the secretion of the insulin equivalent in flies. The other branch projects to glucagon-producing cells and sends a signal inhibiting the secretion of the glucagon equivalent.

When flies consume food, the levels of glucose in their body increase; this excites the CN neuron, which fires the simultaneous signals to stimulate insulin and inhibit glucagon secretion, thereby maintaining the appropriate balance between the hormones and sugar in the blood. The researchers were able to see this happening in the brain in real time by using a combination of cutting-edge fluorescent calcium imaging technology, as well as measuring hormone and sugar levels and applying highly sophisticated molecular genetic techniques.

When flies were not fed, however, the researchers observed a reduction in the activity of CN neuron, a reduction in insulin secretion and an increase in glucagon secretion. These findings indicate that these key hormones are under the direct control of the glucose-sensing neuron. Furthermore, when they silenced the CN neuron rendering dysfunctional CN neuron in flies, these animals experienced an imbalance, resulting in hyperglycemia – high levels of sugars in the blood, similar to what is observed in diabetes in humans. This further suggests that the CN neuron is critical to maintaining glucose homeostasis in animals.

While further research is required to investigate this process in humans, Suh notes this is a significant step forward in the fields of both neurobiology and endocrinology.

“This work lays the foundation for translational research to better understand how this delicate regulatory process is affected by diabetes, obesity, excessive nutrition and diets high in sugar,” Suh said.

Profile: Greg Seong-Bae Suh

seongbaesuh@kaist.ac.kr

Professor Department of Biological Sciences

KAIST

(Figure: A single glucose-excited CN neuron extends bifurcated axonal branches,

one of which innervates insulin producing cells and stimulates their activity an the other axonal branch projects to glucagon producing cells and inhibits their activity.)

2019.10.24 View 18093 -

A Mathematical Model Reveals Long-Distance Cell Communication Mechanism

How can tens of thousands of people in a large football stadium all clap together with the same beat even though they can only hear the people near them clapping?

A combination of a partial differential equation and a synthetic circuit in microbes answers this question. An interdisciplinary collaborative team of Professor Jae Kyoung Kim at KAIST, Professor Krešimir Josić at the University of Houston, and Professor Matt Bennett at Rice University has identified how a large community can communicate with each other almost simultaneously even with very short distance signaling. The research was reported at Nature Chemical Biology.

Cells often communicate using signaling molecules, which can travel only a short distance. Nevertheless, the cells can also communicate over large distances to spur collective action. The team revealed a cell communication mechanism that quickly forms a network of local interactions to spur collective action, even in large communities.

The research team used an engineered transcriptional circuit of combined positive and negative feedback loops in E. coli, which can periodically release two types of signaling molecules: activator and repressor. As the signaling molecules travel over a short distance, cells can only talk to their nearest neighbors. However, cell communities synchronize oscillatory gene expression in spatially extended systems as long as the transcriptional circuit contains a positive feedback loop for the activator.

Professor Kim said that analyzing and understanding such high-dimensional dynamics was extremely difficult. He explained, “That’s why we used high-dimensional partial differential equation to describe the system based on the interactions among various types of molecules.” Surprisingly, the mathematical model accurately simulates the synthesis of the signaling molecules in the cell and their spatial diffusion throughout the chamber and their effect on neighboring cells.

The team simplified the high-dimensional system into a one-dimensional orbit, noting that the system repeats periodically. This allowed them to discover that cells can make one voice when they lowered their own voice and listened to the others. “It turns out the positive feedback loop reduces the distance between moving points and finally makes them move all together. That’s why you clap louder when you hear applause from nearby neighbors and everyone eventually claps together at almost the same time,” said Professor Kim.

Professor Kim added, “Math is a powerful as it simplifies complex thing so that we can find an essential underlying property. This finding would not have been possible without the simplification of complex systems using mathematics."

The National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation, the Robert A. Welch Foundation, the Hamill Foundation, the National Research Foundation of Korea, and the T.J. Park Science Fellowship of POSCO supported the research.

(Figure: Complex molecular interactions among microbial consortia is simplified as interactions among points on a limit cycle (right).)

2019.10.15 View 28015

A Mathematical Model Reveals Long-Distance Cell Communication Mechanism

How can tens of thousands of people in a large football stadium all clap together with the same beat even though they can only hear the people near them clapping?

A combination of a partial differential equation and a synthetic circuit in microbes answers this question. An interdisciplinary collaborative team of Professor Jae Kyoung Kim at KAIST, Professor Krešimir Josić at the University of Houston, and Professor Matt Bennett at Rice University has identified how a large community can communicate with each other almost simultaneously even with very short distance signaling. The research was reported at Nature Chemical Biology.

Cells often communicate using signaling molecules, which can travel only a short distance. Nevertheless, the cells can also communicate over large distances to spur collective action. The team revealed a cell communication mechanism that quickly forms a network of local interactions to spur collective action, even in large communities.

The research team used an engineered transcriptional circuit of combined positive and negative feedback loops in E. coli, which can periodically release two types of signaling molecules: activator and repressor. As the signaling molecules travel over a short distance, cells can only talk to their nearest neighbors. However, cell communities synchronize oscillatory gene expression in spatially extended systems as long as the transcriptional circuit contains a positive feedback loop for the activator.

Professor Kim said that analyzing and understanding such high-dimensional dynamics was extremely difficult. He explained, “That’s why we used high-dimensional partial differential equation to describe the system based on the interactions among various types of molecules.” Surprisingly, the mathematical model accurately simulates the synthesis of the signaling molecules in the cell and their spatial diffusion throughout the chamber and their effect on neighboring cells.

The team simplified the high-dimensional system into a one-dimensional orbit, noting that the system repeats periodically. This allowed them to discover that cells can make one voice when they lowered their own voice and listened to the others. “It turns out the positive feedback loop reduces the distance between moving points and finally makes them move all together. That’s why you clap louder when you hear applause from nearby neighbors and everyone eventually claps together at almost the same time,” said Professor Kim.

Professor Kim added, “Math is a powerful as it simplifies complex thing so that we can find an essential underlying property. This finding would not have been possible without the simplification of complex systems using mathematics."

The National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation, the Robert A. Welch Foundation, the Hamill Foundation, the National Research Foundation of Korea, and the T.J. Park Science Fellowship of POSCO supported the research.

(Figure: Complex molecular interactions among microbial consortia is simplified as interactions among points on a limit cycle (right).)

2019.10.15 View 28015 -

Accurate Detection of Low-Level Somatic Mutation in Intractable Epilepsy

KAIST medical scientists have developed an advanced method for perfectly detecting low-level somatic mutation in patients with intractable epilepsy. Their study showed that deep sequencing replicates of major focal epilepsy genes accurately and efficiently identified low-level somatic mutations in intractable epilepsy.

According to the study, their diagnostic method could increase the accuracy up to 100%, unlike the conventional sequencing analysis, which stands at about 30% accuracy. This work was published in Acta Neuropathologica.

Epilepsy is a neurological disorder common in children. Approximately one third of child patients are diagnosed with intractable epilepsy despite adequate anti-epileptic medication treatment.

Somatic mutations in mTOR pathway genes, SLC35A2, and BRAF are the major genetic causes of intractable epilepsies. A clinical trial to target Focal Cortical Dysplasia type II (FCDII), the mTOR inhibitor is underway at Severance Hospital, their collaborator in Seoul, Korea. However, it is difficult to detect such somatic mutations causing intractable epilepsy because their mutational burden is less than 5%, which is similar to the level of sequencing artifacts. In the clinical field, this has remained a standing challenge for the genetic diagnosis of somatic mutations in intractable epilepsy.

Professor Jeong Ho Lee’s team at the Graduate School of Medical Science and Engineering analyzed paired brain and peripheral tissues from 232 intractable epilepsy patients with various brain pathologies at Severance Hospital using deep sequencing and extracted the major focal epilepsy genes.

They narrowed down target genes to eight major focal epilepsy genes, eliminating almost all of the false positive calls using deep targeted sequencing. As a result, the advanced method robustly increased the accuracy and enabled them to detect low-level somatic mutations in unmatched Formalin Fixed Paraffin Embedded (FFPE) brain samples, the most clinically relevant samples.

Professor Lee conducted this study in collaboration with Professor Dong Suk Kim and Hoon-Chul Kang at Severance Hospital of Yonsei University. He said, “This advanced method of genetic analysis will improve overall patient care by providing more comprehensive genetic counseling and informing decisions on alternative treatments.”

Professor Lee has investigated low-level somatic mutations arising in the brain for a decade. He is developing innovative diagnostics and therapeutics for untreatable brain disorders including intractable epilepsy and glioblastoma at a tech-startup called SoVarGen. “All of the technologies we used during the research were transferred to the company. This research gave us very good momentum to reach the next phase of our startup,” he remarked.

The work was supported by grants from the Suh Kyungbae Foundation, a National Research Foundation of Korea grant funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT, the Korean Health Technology R&D Project from the Ministry of Health & Welfare, and the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development.

(Figure: Landscape of somatic and germline mutations identified in intractable epilepsy patients. a Signaling pathways for all of the mutated genes identified in this study. Bold: somatic mutation, Regular: germline mutation. b The distribution of variant allelic frequencies (VAFs) of identified somatic mutations. c The detecting rate and types of identified mutations according to histopathology. Yellow: somatic mutations, green: two-hit mutations, grey: germline mutations.)

2019.08.14 View 29398

Accurate Detection of Low-Level Somatic Mutation in Intractable Epilepsy

KAIST medical scientists have developed an advanced method for perfectly detecting low-level somatic mutation in patients with intractable epilepsy. Their study showed that deep sequencing replicates of major focal epilepsy genes accurately and efficiently identified low-level somatic mutations in intractable epilepsy.

According to the study, their diagnostic method could increase the accuracy up to 100%, unlike the conventional sequencing analysis, which stands at about 30% accuracy. This work was published in Acta Neuropathologica.

Epilepsy is a neurological disorder common in children. Approximately one third of child patients are diagnosed with intractable epilepsy despite adequate anti-epileptic medication treatment.

Somatic mutations in mTOR pathway genes, SLC35A2, and BRAF are the major genetic causes of intractable epilepsies. A clinical trial to target Focal Cortical Dysplasia type II (FCDII), the mTOR inhibitor is underway at Severance Hospital, their collaborator in Seoul, Korea. However, it is difficult to detect such somatic mutations causing intractable epilepsy because their mutational burden is less than 5%, which is similar to the level of sequencing artifacts. In the clinical field, this has remained a standing challenge for the genetic diagnosis of somatic mutations in intractable epilepsy.

Professor Jeong Ho Lee’s team at the Graduate School of Medical Science and Engineering analyzed paired brain and peripheral tissues from 232 intractable epilepsy patients with various brain pathologies at Severance Hospital using deep sequencing and extracted the major focal epilepsy genes.

They narrowed down target genes to eight major focal epilepsy genes, eliminating almost all of the false positive calls using deep targeted sequencing. As a result, the advanced method robustly increased the accuracy and enabled them to detect low-level somatic mutations in unmatched Formalin Fixed Paraffin Embedded (FFPE) brain samples, the most clinically relevant samples.

Professor Lee conducted this study in collaboration with Professor Dong Suk Kim and Hoon-Chul Kang at Severance Hospital of Yonsei University. He said, “This advanced method of genetic analysis will improve overall patient care by providing more comprehensive genetic counseling and informing decisions on alternative treatments.”

Professor Lee has investigated low-level somatic mutations arising in the brain for a decade. He is developing innovative diagnostics and therapeutics for untreatable brain disorders including intractable epilepsy and glioblastoma at a tech-startup called SoVarGen. “All of the technologies we used during the research were transferred to the company. This research gave us very good momentum to reach the next phase of our startup,” he remarked.

The work was supported by grants from the Suh Kyungbae Foundation, a National Research Foundation of Korea grant funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT, the Korean Health Technology R&D Project from the Ministry of Health & Welfare, and the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development.

(Figure: Landscape of somatic and germline mutations identified in intractable epilepsy patients. a Signaling pathways for all of the mutated genes identified in this study. Bold: somatic mutation, Regular: germline mutation. b The distribution of variant allelic frequencies (VAFs) of identified somatic mutations. c The detecting rate and types of identified mutations according to histopathology. Yellow: somatic mutations, green: two-hit mutations, grey: germline mutations.)

2019.08.14 View 29398 -

Deciphering Brain Somatic Mutations Associated with Alzheimer's Disease

Researchers have found a potential link between non-inherited somatic mutations in the brain and the progression of Alzheimer’s disease

Researchers have identified somatic mutations in the brain that could contribute to the development of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Their findings were published in the journal Nature Communications last week.

Decades worth of research has identified inherited mutations that lead to early-onset familial AD. Inherited mutations, however, are behind at most half the cases of late onset sporadic AD, in which there is no family history of the disease. But the genetic factors causing the other half of these sporadic cases have been unclear.

Professor Jeong Ho Lee at the Graduate School of Medical Science and Engineering and colleagues analysed the DNA present in post-mortem hippocampal formations and in blood samples from people aged 70 to 96 with AD and age-matched controls. They specifically looked for non-inherited somatic mutations in their brains using high-depth whole exome sequencing.

The team developed a bioinformatics pipeline that enabled them to detect low-level brain somatic single nucleotide variations (SNVs) – mutations that involve the substitution of a single nucleotide with another nucleotide. Brain somatic SNVs have been reported on and accumulate throughout our lives and can sometimes be associated with a range of neurological diseases.

The number of somatic SNVs did not differ between individuals with AD and non-demented controls. Interestingly, somatic SNVs in AD brains arise about 4.8 times more slowly than in blood. When the team performed gene-set enrichment tests, 26.9 percent of the AD brain samples had pathogenic brain somatic SNVs known to be linked to hyperphosphorylation of tau proteins, which is one of major hallmarks of AD.