mathematical+model

-

Scientist Discover How Circadian Rhythm Can Be Both Strong and Flexible

Study reveals that master and slave oscillators function via different molecular mechanisms

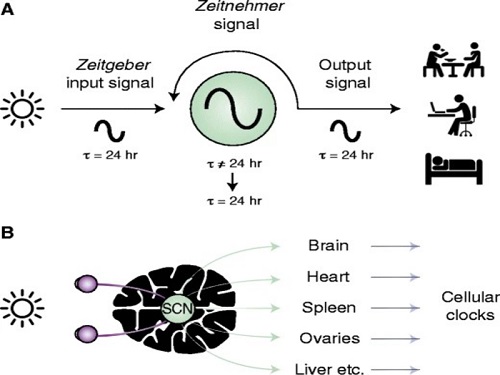

From tiny fruit flies to human beings, all animals on Earth maintain their daily rhythms based on their internal circadian clock. The circadian clock enables organisms to undergo rhythmic changes in behavior and physiology based on a 24-hour circadian cycle. For example, our own biological clock tells our brain to release melatonin, a sleep-inducing hormone, at night time.

The discovery of the molecular mechanism of the circadian clock was bestowed the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2017. From what we know, no one centralized clock is responsible for our circadian cycles. Instead, it operates in a hierarchical network where there are “master pacemaker” and “slave oscillator”.

The master pacemaker receives various input signals from the environment such as light. The master then drives the slave oscillator that regulates various outputs such as sleep, feeding, and metabolism. Despite the different roles of the pacemaker neurons, they are known to share common molecular mechanisms that are well conserved in all lifeforms. For example, interlocked systems of multiple transcriptional-translational feedback loops (TTFLs) composed of core clock proteins have been deeply studied in fruit flies.

However, there is still much that we need to learn about our own biological clock. The hierarchically-organized nature of master and slave clock neurons leads to a prevailing belief that they share an identical molecular clockwork. At the same time, the different roles they serve in regulating bodily rhythms also raise the question of whether they might function under different molecular clockworks.

Research team led by Professor Kim Jae Kyoung from the Department of Mathematical Sciences, a chief investigator at the Biomedical Mathematics Group at the Institute for Basic Science, used a combination of mathematical and experimental approaches using fruit flies to answer this question. The team found that the master clock and the slave clock operate via different molecular mechanisms.

In both master and slave neurons of fruit flies, a circadian rhythm-related protein called PER is produced and degraded at different rates depending on the time of the day. Previously, the team found that the master clock neuron (sLNvs) and the slave clock neuron (DN1ps) have different profiles of PER in wild-type and Clk-Δ mutant Drosophila. This hinted that there might be a potential difference in molecular clockworks between the master and slave clock neurons.

However, due to the complexity of the molecular clockwork, it was challenging to identify the source of such differences. Thus, the team developed a mathematical model describing the molecular clockworks of the master and slave clocks. Then, all possible molecular differences between the master and slave clock neurons were systematically investigated by using computer simulations. The model predicted that PER is more efficiently produced and then rapidly degraded in the master clock compared to the slave clock neurons. This prediction was then confirmed by the follow-up experiments using animal.

Then, why do the master clock neurons have such different molecular properties from the slave clock neurons? To answer this question, the research team again used the combination of mathematical model simulation and experiments. It was found that the faster rate of synthesis of PER in the master clock neurons allows them to generate synchronized rhythms with a high level of amplitude. Generation of such a strong rhythm with high amplitude is critical to delivering clear signals to slave clock neurons.

However, such strong rhythms would typically be unfavorable when it comes to adapting to environmental changes. These include natural causes such as different daylight hours across summer and winter seasons, up to more extreme artificial cases such as jet lag that occurs after international travel. Thanks to the distinct property of the master clock neurons, it is able to undergo phase dispersion when the standard light-dark cycle is disrupted, drastically reducing the level of PER. The master clock neurons can then easily adapt to the new diurnal cycle. Our master pacemaker’s plasticity explains how we can quickly adjust to the new time zones after international flights after just a brief period of jet lag.

It is hoped that the findings of this study can have future clinical implications when it comes to treating various disorders that affect our circadian rhythm. Professor Kim notes, “When the circadian clock loses its robustness and flexibility, the circadian rhythms sleep disorders can occur. As this study identifies the molecular mechanism that generates robustness and flexibility of the circadian clock, it can facilitate the identification of the cause of and treatment strategy for the circadian rhythm sleep disorders.” This work was supported by the Human Frontier Science Program.

-PublicationEui Min Jeong, Miri Kwon, Eunjoo Cho, Sang Hyuk Lee, Hyun Kim, Eun Young Kim, and Jae Kyoung Kim, “Systematic modeling-driven experiments identify distinct molecularclockworks underlying hierarchically organized pacemaker neurons,” February 22, 2022, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America

-ProfileProfessor Jae Kyoung KimDepartment of Mathematical SciencesKAIST

2022.02.23 View 10128

Scientist Discover How Circadian Rhythm Can Be Both Strong and Flexible

Study reveals that master and slave oscillators function via different molecular mechanisms

From tiny fruit flies to human beings, all animals on Earth maintain their daily rhythms based on their internal circadian clock. The circadian clock enables organisms to undergo rhythmic changes in behavior and physiology based on a 24-hour circadian cycle. For example, our own biological clock tells our brain to release melatonin, a sleep-inducing hormone, at night time.

The discovery of the molecular mechanism of the circadian clock was bestowed the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2017. From what we know, no one centralized clock is responsible for our circadian cycles. Instead, it operates in a hierarchical network where there are “master pacemaker” and “slave oscillator”.

The master pacemaker receives various input signals from the environment such as light. The master then drives the slave oscillator that regulates various outputs such as sleep, feeding, and metabolism. Despite the different roles of the pacemaker neurons, they are known to share common molecular mechanisms that are well conserved in all lifeforms. For example, interlocked systems of multiple transcriptional-translational feedback loops (TTFLs) composed of core clock proteins have been deeply studied in fruit flies.

However, there is still much that we need to learn about our own biological clock. The hierarchically-organized nature of master and slave clock neurons leads to a prevailing belief that they share an identical molecular clockwork. At the same time, the different roles they serve in regulating bodily rhythms also raise the question of whether they might function under different molecular clockworks.

Research team led by Professor Kim Jae Kyoung from the Department of Mathematical Sciences, a chief investigator at the Biomedical Mathematics Group at the Institute for Basic Science, used a combination of mathematical and experimental approaches using fruit flies to answer this question. The team found that the master clock and the slave clock operate via different molecular mechanisms.

In both master and slave neurons of fruit flies, a circadian rhythm-related protein called PER is produced and degraded at different rates depending on the time of the day. Previously, the team found that the master clock neuron (sLNvs) and the slave clock neuron (DN1ps) have different profiles of PER in wild-type and Clk-Δ mutant Drosophila. This hinted that there might be a potential difference in molecular clockworks between the master and slave clock neurons.

However, due to the complexity of the molecular clockwork, it was challenging to identify the source of such differences. Thus, the team developed a mathematical model describing the molecular clockworks of the master and slave clocks. Then, all possible molecular differences between the master and slave clock neurons were systematically investigated by using computer simulations. The model predicted that PER is more efficiently produced and then rapidly degraded in the master clock compared to the slave clock neurons. This prediction was then confirmed by the follow-up experiments using animal.

Then, why do the master clock neurons have such different molecular properties from the slave clock neurons? To answer this question, the research team again used the combination of mathematical model simulation and experiments. It was found that the faster rate of synthesis of PER in the master clock neurons allows them to generate synchronized rhythms with a high level of amplitude. Generation of such a strong rhythm with high amplitude is critical to delivering clear signals to slave clock neurons.

However, such strong rhythms would typically be unfavorable when it comes to adapting to environmental changes. These include natural causes such as different daylight hours across summer and winter seasons, up to more extreme artificial cases such as jet lag that occurs after international travel. Thanks to the distinct property of the master clock neurons, it is able to undergo phase dispersion when the standard light-dark cycle is disrupted, drastically reducing the level of PER. The master clock neurons can then easily adapt to the new diurnal cycle. Our master pacemaker’s plasticity explains how we can quickly adjust to the new time zones after international flights after just a brief period of jet lag.

It is hoped that the findings of this study can have future clinical implications when it comes to treating various disorders that affect our circadian rhythm. Professor Kim notes, “When the circadian clock loses its robustness and flexibility, the circadian rhythms sleep disorders can occur. As this study identifies the molecular mechanism that generates robustness and flexibility of the circadian clock, it can facilitate the identification of the cause of and treatment strategy for the circadian rhythm sleep disorders.” This work was supported by the Human Frontier Science Program.

-PublicationEui Min Jeong, Miri Kwon, Eunjoo Cho, Sang Hyuk Lee, Hyun Kim, Eun Young Kim, and Jae Kyoung Kim, “Systematic modeling-driven experiments identify distinct molecularclockworks underlying hierarchically organized pacemaker neurons,” February 22, 2022, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America

-ProfileProfessor Jae Kyoung KimDepartment of Mathematical SciencesKAIST

2022.02.23 View 10128 -

Connecting the Dots to Find New Treatments for Breast Cancer

Systems biologists uncovered new ways of cancer cell reprogramming to treat drug-resistant cancers

Scientists at KAIST believe they may have found a way to reverse an aggressive, treatment-resistant type of breast cancer into a less dangerous kind that responds well to treatment. The study involved the use of mathematical models to untangle the complex genetic and molecular interactions that occur in the two types of breast cancer, but could be extended to find ways for treating many others. The study’s findings were published in the journal Cancer Research.

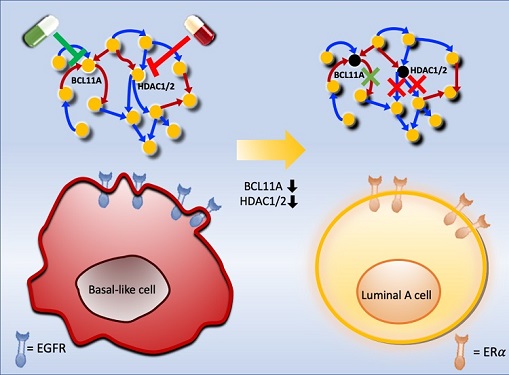

Basal-like tumours are the most aggressive type of breast cancer, with the worst prognosis. Chemotherapy is the only available treatment option, but patients experience high recurrence rates. On the other hand, luminal-A breast cancer responds well to drugs that specifically target a receptor on their cell surfaces, called estrogen receptor alpha (ERα).

KAIST systems biologist Kwang-Hyun Cho and colleagues analyzed the complex molecular and genetic interactions of basal-like and luminal-A breast cancers to find out if there might be a way to switch the former to the latter and give patients a better chance to respond to treatment.

To do this, they accessed large amounts of cancer and patient data to understand which genes and molecules are involved in the two types. They then input this data into a mathematical model that represents genes, proteins and molecules as dots and the interactions between them as lines. The model can be used to conduct simulations and see how interactions change when certain genes are turned on or off.

“There have been a tremendous number of studies trying to find therapeutic targets for treating basal-like breast cancer patients,” says Cho. “But clinical trials have failed due to the complex and dynamic nature of cancer. To overcome this issue, we looked at breast cancer cells as a complex network system and implemented a systems biological approach to unravel the underlying mechanisms that would allow us to reprogram basal-like into luminal-A breast cancer cells.”

Using this approach, followed by experimental validation on real breast cancer cells, the team found that turning off two key gene regulators, called BCL11A and HDAC1/2, switched a basal-like cancer signalling pathway into a different one used by luminal-A cancer cells. The switch reprograms the cancer cells and makes them more responsive to drugs that target ERα receptors. However, further tests will be needed to confirm that this also works in animal models and eventually humans.

“Our study demonstrates that the systems biological approach can be useful for identifying novel therapeutic targets,” says Cho.

The researchers are now expanding its breast cancer network model to include all breast cancer subtypes. Their ultimate aim is to identify more drug targets and to understand the mechanisms that could drive drug-resistant cells to turn into drug-sensitive ones.

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea, the Ministry of Science and ICT, Electronics and Telecommunications Research Institute, and the KAIST Grand Challenge 30 Project.

-Publication Sea R. Choi, Chae Young Hwang, Jonghoon Lee, and Kwang-Hyun Cho, “Network Analysis Identifies Regulators of Basal-like Breast Cancer Reprogramming and Endocrine TherapyVulnerability,” Cancer Research, November 30. (doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-21-0621)

-ProfileProfessor Kwang-Hyun ChoLaboratory for Systems Biology and Bio-Inspired EngineeringDepartment of Bio and Brain EngineeringKAIST

2021.12.07 View 11099

Connecting the Dots to Find New Treatments for Breast Cancer

Systems biologists uncovered new ways of cancer cell reprogramming to treat drug-resistant cancers

Scientists at KAIST believe they may have found a way to reverse an aggressive, treatment-resistant type of breast cancer into a less dangerous kind that responds well to treatment. The study involved the use of mathematical models to untangle the complex genetic and molecular interactions that occur in the two types of breast cancer, but could be extended to find ways for treating many others. The study’s findings were published in the journal Cancer Research.

Basal-like tumours are the most aggressive type of breast cancer, with the worst prognosis. Chemotherapy is the only available treatment option, but patients experience high recurrence rates. On the other hand, luminal-A breast cancer responds well to drugs that specifically target a receptor on their cell surfaces, called estrogen receptor alpha (ERα).

KAIST systems biologist Kwang-Hyun Cho and colleagues analyzed the complex molecular and genetic interactions of basal-like and luminal-A breast cancers to find out if there might be a way to switch the former to the latter and give patients a better chance to respond to treatment.

To do this, they accessed large amounts of cancer and patient data to understand which genes and molecules are involved in the two types. They then input this data into a mathematical model that represents genes, proteins and molecules as dots and the interactions between them as lines. The model can be used to conduct simulations and see how interactions change when certain genes are turned on or off.

“There have been a tremendous number of studies trying to find therapeutic targets for treating basal-like breast cancer patients,” says Cho. “But clinical trials have failed due to the complex and dynamic nature of cancer. To overcome this issue, we looked at breast cancer cells as a complex network system and implemented a systems biological approach to unravel the underlying mechanisms that would allow us to reprogram basal-like into luminal-A breast cancer cells.”

Using this approach, followed by experimental validation on real breast cancer cells, the team found that turning off two key gene regulators, called BCL11A and HDAC1/2, switched a basal-like cancer signalling pathway into a different one used by luminal-A cancer cells. The switch reprograms the cancer cells and makes them more responsive to drugs that target ERα receptors. However, further tests will be needed to confirm that this also works in animal models and eventually humans.

“Our study demonstrates that the systems biological approach can be useful for identifying novel therapeutic targets,” says Cho.

The researchers are now expanding its breast cancer network model to include all breast cancer subtypes. Their ultimate aim is to identify more drug targets and to understand the mechanisms that could drive drug-resistant cells to turn into drug-sensitive ones.

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea, the Ministry of Science and ICT, Electronics and Telecommunications Research Institute, and the KAIST Grand Challenge 30 Project.

-Publication Sea R. Choi, Chae Young Hwang, Jonghoon Lee, and Kwang-Hyun Cho, “Network Analysis Identifies Regulators of Basal-like Breast Cancer Reprogramming and Endocrine TherapyVulnerability,” Cancer Research, November 30. (doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-21-0621)

-ProfileProfessor Kwang-Hyun ChoLaboratory for Systems Biology and Bio-Inspired EngineeringDepartment of Bio and Brain EngineeringKAIST

2021.12.07 View 11099 -

A Mathematical Model Reveals Long-Distance Cell Communication Mechanism

How can tens of thousands of people in a large football stadium all clap together with the same beat even though they can only hear the people near them clapping?

A combination of a partial differential equation and a synthetic circuit in microbes answers this question. An interdisciplinary collaborative team of Professor Jae Kyoung Kim at KAIST, Professor Krešimir Josić at the University of Houston, and Professor Matt Bennett at Rice University has identified how a large community can communicate with each other almost simultaneously even with very short distance signaling. The research was reported at Nature Chemical Biology.

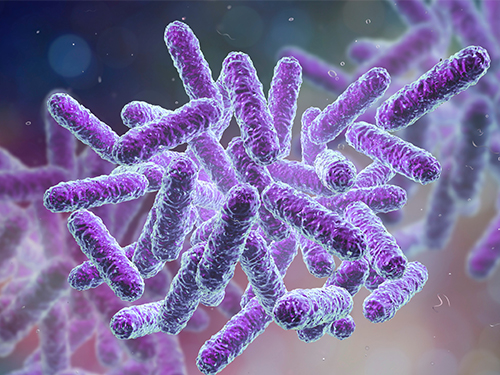

Cells often communicate using signaling molecules, which can travel only a short distance. Nevertheless, the cells can also communicate over large distances to spur collective action. The team revealed a cell communication mechanism that quickly forms a network of local interactions to spur collective action, even in large communities.

The research team used an engineered transcriptional circuit of combined positive and negative feedback loops in E. coli, which can periodically release two types of signaling molecules: activator and repressor. As the signaling molecules travel over a short distance, cells can only talk to their nearest neighbors. However, cell communities synchronize oscillatory gene expression in spatially extended systems as long as the transcriptional circuit contains a positive feedback loop for the activator.

Professor Kim said that analyzing and understanding such high-dimensional dynamics was extremely difficult. He explained, “That’s why we used high-dimensional partial differential equation to describe the system based on the interactions among various types of molecules.” Surprisingly, the mathematical model accurately simulates the synthesis of the signaling molecules in the cell and their spatial diffusion throughout the chamber and their effect on neighboring cells.

The team simplified the high-dimensional system into a one-dimensional orbit, noting that the system repeats periodically. This allowed them to discover that cells can make one voice when they lowered their own voice and listened to the others. “It turns out the positive feedback loop reduces the distance between moving points and finally makes them move all together. That’s why you clap louder when you hear applause from nearby neighbors and everyone eventually claps together at almost the same time,” said Professor Kim.

Professor Kim added, “Math is a powerful as it simplifies complex thing so that we can find an essential underlying property. This finding would not have been possible without the simplification of complex systems using mathematics."

The National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation, the Robert A. Welch Foundation, the Hamill Foundation, the National Research Foundation of Korea, and the T.J. Park Science Fellowship of POSCO supported the research.

(Figure: Complex molecular interactions among microbial consortia is simplified as interactions among points on a limit cycle (right).)

2019.10.15 View 27849

A Mathematical Model Reveals Long-Distance Cell Communication Mechanism

How can tens of thousands of people in a large football stadium all clap together with the same beat even though they can only hear the people near them clapping?

A combination of a partial differential equation and a synthetic circuit in microbes answers this question. An interdisciplinary collaborative team of Professor Jae Kyoung Kim at KAIST, Professor Krešimir Josić at the University of Houston, and Professor Matt Bennett at Rice University has identified how a large community can communicate with each other almost simultaneously even with very short distance signaling. The research was reported at Nature Chemical Biology.

Cells often communicate using signaling molecules, which can travel only a short distance. Nevertheless, the cells can also communicate over large distances to spur collective action. The team revealed a cell communication mechanism that quickly forms a network of local interactions to spur collective action, even in large communities.

The research team used an engineered transcriptional circuit of combined positive and negative feedback loops in E. coli, which can periodically release two types of signaling molecules: activator and repressor. As the signaling molecules travel over a short distance, cells can only talk to their nearest neighbors. However, cell communities synchronize oscillatory gene expression in spatially extended systems as long as the transcriptional circuit contains a positive feedback loop for the activator.

Professor Kim said that analyzing and understanding such high-dimensional dynamics was extremely difficult. He explained, “That’s why we used high-dimensional partial differential equation to describe the system based on the interactions among various types of molecules.” Surprisingly, the mathematical model accurately simulates the synthesis of the signaling molecules in the cell and their spatial diffusion throughout the chamber and their effect on neighboring cells.

The team simplified the high-dimensional system into a one-dimensional orbit, noting that the system repeats periodically. This allowed them to discover that cells can make one voice when they lowered their own voice and listened to the others. “It turns out the positive feedback loop reduces the distance between moving points and finally makes them move all together. That’s why you clap louder when you hear applause from nearby neighbors and everyone eventually claps together at almost the same time,” said Professor Kim.

Professor Kim added, “Math is a powerful as it simplifies complex thing so that we can find an essential underlying property. This finding would not have been possible without the simplification of complex systems using mathematics."

The National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation, the Robert A. Welch Foundation, the Hamill Foundation, the National Research Foundation of Korea, and the T.J. Park Science Fellowship of POSCO supported the research.

(Figure: Complex molecular interactions among microbial consortia is simplified as interactions among points on a limit cycle (right).)

2019.10.15 View 27849 -

Soul-Searching & Odds-Defying Determination: A Commencement Story of Dr. Tae-Hyun Oh

(Dr. Tae-Hyun Oh, one of the 2736 graduates of the 2018)

Each and every one of the 2,736 graduates has come a long way to the 2018 Commencement. Tae-Hyun Oh, who just started his new research career at MIT after completing his Ph.D. at KAIST, is no exception.

Unlike the most KAIST freshmen straight out of the ingenious science academies of Korea, he is among the many who endured very challenging and turbulent adolescent years. Buffeted by family instability and struggling during his time at school, he saw himself trapped by seemingly impenetrable barriers. His mother, who hated to see his struggling, advised him to take a break to reflect on who he is and what he wanted to do.

After dropping out of high school in his first year, ways to make money and support his family occupied his thoughts. He took on odd jobs from a car body shop to a gas station, but the real world was very tough and sometimes even cruel to the high school dropout.

Bias and prejudice stigmatizing dropouts hurt him so much. He often overheard a parent who dropped by the body shop that he worked in saying, “If you do not study hard, you will end up like this guy.” Hearing such things terrified him and awoke his sense of purpose. So he decided to do something meaningful and be a better man than he was.

“I didn’t like the person I was growing up to become. I needed to find myself and get away from the place I was growing up. It was my adventure and it was the best decision I ever made,” says Oh.

After completing his high school diploma national certificate, he planned to apply to an engineering college. On his second try, he gained admission into the Department of Electrical Engineering at Kwang Woon University with a full scholarship. He was so thrilled for this opportunity and hoped he could do well at college. Signal processing and image processing became the interest of his research and he finished his undergraduate degree summa cum laude.

Gaining confidence in his studies, he searched around graduate school department websites in Korea to select the path he was interested in. Among others, the Robotics and Computer Vision Lab of Professor In-So Kweon at the Department of Electrical Engineering at KAIST was attractive to him.

Professor Kweon’s lab is globally renowned for robot vision technology. Their technologies were applied into HUBO, the KAIST-developed bimodal humanoid robot that won the 2015 DARPA Challenges.

“I am so appreciate of Professor Kweon, who accepted and guided me,” he said. Under Professor Kweon’s advising, he could finish his Master’s and Ph.D. courses in seven years. The mathematical modeling on fundamental computer algorithms became his main research topic.

While at KAIST, his academic research has blossomed. He won a total of 13 research prizes sponsored by corporations at home and abroad such as Kolon, Samsung, Hyundai Motors, and Qualcomm.

In 2015, he won the Microsoft Research Asia Fellowship as the sole Korean among 13 Ph.D. candidates in the Asian region. With the MSRA fellowship, he could intern at the MS Research Beijing Office for half a year and then in Redmond, Washington in the US.

“Professor Kweon’s lab filled me up with knowledge. Whenever I presented our team’s paper at an international conference, I was amazed by the strong interest shown by foreign experts, researchers, and professors. Their strong support and interest encouraged me a lot. I was fully charged with the belief that I could go abroad and explore more opportunities,” he said.

Dr. Oh, who completed his dissertation last fall, now works at the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science at MIT under Professor Wojciech Matusik.

“I think the research environment at KAIST is on par with MIT. I have very rich resources for my studies and research at both schools, but at MIT the working culture is a little different and it remains a big challenge for me. I am still not familiar with collaborative work with colleagues from very diverse backgrounds and countries, and to persuade them and communicate with them is very tough. But I think I am getting better and better,” he said.

Oh, who is an avid computer game player as well, said life seems to be a game. The level of the game will be upgraded to the next level after something is accomplished. He feels great joy when he is moving up and he believes such diverse experiences have helped him become a better person day by day. Once he identified what gave him a strong sense of purpose, he wasn’t stressed out by his studies any more. He was so excited to be able to follow his passion and is ready for the next challenge.

2018.02.23 View 11420

Soul-Searching & Odds-Defying Determination: A Commencement Story of Dr. Tae-Hyun Oh

(Dr. Tae-Hyun Oh, one of the 2736 graduates of the 2018)

Each and every one of the 2,736 graduates has come a long way to the 2018 Commencement. Tae-Hyun Oh, who just started his new research career at MIT after completing his Ph.D. at KAIST, is no exception.

Unlike the most KAIST freshmen straight out of the ingenious science academies of Korea, he is among the many who endured very challenging and turbulent adolescent years. Buffeted by family instability and struggling during his time at school, he saw himself trapped by seemingly impenetrable barriers. His mother, who hated to see his struggling, advised him to take a break to reflect on who he is and what he wanted to do.

After dropping out of high school in his first year, ways to make money and support his family occupied his thoughts. He took on odd jobs from a car body shop to a gas station, but the real world was very tough and sometimes even cruel to the high school dropout.

Bias and prejudice stigmatizing dropouts hurt him so much. He often overheard a parent who dropped by the body shop that he worked in saying, “If you do not study hard, you will end up like this guy.” Hearing such things terrified him and awoke his sense of purpose. So he decided to do something meaningful and be a better man than he was.

“I didn’t like the person I was growing up to become. I needed to find myself and get away from the place I was growing up. It was my adventure and it was the best decision I ever made,” says Oh.

After completing his high school diploma national certificate, he planned to apply to an engineering college. On his second try, he gained admission into the Department of Electrical Engineering at Kwang Woon University with a full scholarship. He was so thrilled for this opportunity and hoped he could do well at college. Signal processing and image processing became the interest of his research and he finished his undergraduate degree summa cum laude.

Gaining confidence in his studies, he searched around graduate school department websites in Korea to select the path he was interested in. Among others, the Robotics and Computer Vision Lab of Professor In-So Kweon at the Department of Electrical Engineering at KAIST was attractive to him.

Professor Kweon’s lab is globally renowned for robot vision technology. Their technologies were applied into HUBO, the KAIST-developed bimodal humanoid robot that won the 2015 DARPA Challenges.

“I am so appreciate of Professor Kweon, who accepted and guided me,” he said. Under Professor Kweon’s advising, he could finish his Master’s and Ph.D. courses in seven years. The mathematical modeling on fundamental computer algorithms became his main research topic.

While at KAIST, his academic research has blossomed. He won a total of 13 research prizes sponsored by corporations at home and abroad such as Kolon, Samsung, Hyundai Motors, and Qualcomm.

In 2015, he won the Microsoft Research Asia Fellowship as the sole Korean among 13 Ph.D. candidates in the Asian region. With the MSRA fellowship, he could intern at the MS Research Beijing Office for half a year and then in Redmond, Washington in the US.

“Professor Kweon’s lab filled me up with knowledge. Whenever I presented our team’s paper at an international conference, I was amazed by the strong interest shown by foreign experts, researchers, and professors. Their strong support and interest encouraged me a lot. I was fully charged with the belief that I could go abroad and explore more opportunities,” he said.

Dr. Oh, who completed his dissertation last fall, now works at the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science at MIT under Professor Wojciech Matusik.

“I think the research environment at KAIST is on par with MIT. I have very rich resources for my studies and research at both schools, but at MIT the working culture is a little different and it remains a big challenge for me. I am still not familiar with collaborative work with colleagues from very diverse backgrounds and countries, and to persuade them and communicate with them is very tough. But I think I am getting better and better,” he said.

Oh, who is an avid computer game player as well, said life seems to be a game. The level of the game will be upgraded to the next level after something is accomplished. He feels great joy when he is moving up and he believes such diverse experiences have helped him become a better person day by day. Once he identified what gave him a strong sense of purpose, he wasn’t stressed out by his studies any more. He was so excited to be able to follow his passion and is ready for the next challenge.

2018.02.23 View 11420