Department+of+Biological+Science

-

KAIST Team Develops Optogenetic Platform for Spatiotemporal Control of Protein and mRNA Storage and Release

<Dr. Chaeyeon Lee, Professor Won Do Heo from Department of Biological Sciences>

A KAIST research team led by Professor Won Do Heo (Department of Biological Sciences) has developed an optogenetic platform, RELISR (REversible LIght-induced Store and Release), that enables precise spatiotemporal control over the storage and release of proteins and mRNAs in living cells and animals.

Traditional optogenetic condensate systems have been limited by their reliance on non-specific multivalent interactions, which can lead to unintended sequestration or release of endogenous molecules. RELISR overcomes these limitations by employing highly specific protein–protein (nanobody–antigen) and protein–RNA (MCP–MS2) interactions, enabling the selective and reversible compartmentalization of target proteins or mRNAs within engineered, membrane-less condensates.

In the dark, RELISR stably sequesters target molecules within condensates, physically isolating them from the cellular environment. Upon blue light stimulation, the condensates rapidly dissolve, releasing the stored proteins or mRNAs, which immediately regain their cellular functions or translational competency. This allows for reversible and rapid modulation of molecular activities in response to optical cues.

The research team demonstrated that RELISR enables temporal and spatial regulation of protein activity and mRNA translation in various cell types, including cultured neurons and mouse liver tissue. Comparative studies showed that RELISR provides more robust and reversible control of translation than previous systems based on spatial translocation.

While previous optogenetic systems such as LARIAT (Lee et al., Nature Methods, 2014) and mRNA-LARIAT (Kim et al., Nat. Cell Biol., 2019) enabled the selective sequestration of proteins or mRNAs into membrane-less condensates in response to light, they were primarily limited to the trapping phase. The RELISR platform introduced in this study establishes a new paradigm by enabling both the targeted storage of proteins and mRNAs and their rapid, light-triggered release. This approach allows researchers to not only confine molecular function on demand, but also to restore activity with precise temporal control.

Professor Heo stated, “RELISR is a versatile optogenetic tool that enables the precise control of protein and mRNA function at defined times and locations in living systems. We anticipate this platform will be broadly applicable for studies of cell signaling, neural circuits, and therapeutic development. Furthermore, the combination of RELISR with genome editing or tissue-targeted delivery could further expand its utility for molecular medicine.”

This research was conducted by first author Dr. Chaeyeon Lee, under the supervision of Professor Heo, with contributions from Dr. Daseuli Yu (co-corresponding author) and Professor YongKeun Park (co-corresponding author, Department of Physics), whose group performed quantitative imaging analyses of biophysical changes induced by RELISR in cells.

The findings were published in Nature Communications (July 7, 2025; DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-61322-y). This work was supported by the Samsung Future Technology Foundation and the National Research Foundation of Korea.

2025.07.23 View 97

KAIST Team Develops Optogenetic Platform for Spatiotemporal Control of Protein and mRNA Storage and Release

<Dr. Chaeyeon Lee, Professor Won Do Heo from Department of Biological Sciences>

A KAIST research team led by Professor Won Do Heo (Department of Biological Sciences) has developed an optogenetic platform, RELISR (REversible LIght-induced Store and Release), that enables precise spatiotemporal control over the storage and release of proteins and mRNAs in living cells and animals.

Traditional optogenetic condensate systems have been limited by their reliance on non-specific multivalent interactions, which can lead to unintended sequestration or release of endogenous molecules. RELISR overcomes these limitations by employing highly specific protein–protein (nanobody–antigen) and protein–RNA (MCP–MS2) interactions, enabling the selective and reversible compartmentalization of target proteins or mRNAs within engineered, membrane-less condensates.

In the dark, RELISR stably sequesters target molecules within condensates, physically isolating them from the cellular environment. Upon blue light stimulation, the condensates rapidly dissolve, releasing the stored proteins or mRNAs, which immediately regain their cellular functions or translational competency. This allows for reversible and rapid modulation of molecular activities in response to optical cues.

The research team demonstrated that RELISR enables temporal and spatial regulation of protein activity and mRNA translation in various cell types, including cultured neurons and mouse liver tissue. Comparative studies showed that RELISR provides more robust and reversible control of translation than previous systems based on spatial translocation.

While previous optogenetic systems such as LARIAT (Lee et al., Nature Methods, 2014) and mRNA-LARIAT (Kim et al., Nat. Cell Biol., 2019) enabled the selective sequestration of proteins or mRNAs into membrane-less condensates in response to light, they were primarily limited to the trapping phase. The RELISR platform introduced in this study establishes a new paradigm by enabling both the targeted storage of proteins and mRNAs and their rapid, light-triggered release. This approach allows researchers to not only confine molecular function on demand, but also to restore activity with precise temporal control.

Professor Heo stated, “RELISR is a versatile optogenetic tool that enables the precise control of protein and mRNA function at defined times and locations in living systems. We anticipate this platform will be broadly applicable for studies of cell signaling, neural circuits, and therapeutic development. Furthermore, the combination of RELISR with genome editing or tissue-targeted delivery could further expand its utility for molecular medicine.”

This research was conducted by first author Dr. Chaeyeon Lee, under the supervision of Professor Heo, with contributions from Dr. Daseuli Yu (co-corresponding author) and Professor YongKeun Park (co-corresponding author, Department of Physics), whose group performed quantitative imaging analyses of biophysical changes induced by RELISR in cells.

The findings were published in Nature Communications (July 7, 2025; DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-61322-y). This work was supported by the Samsung Future Technology Foundation and the National Research Foundation of Korea.

2025.07.23 View 97 -

KAIST Enhances Immunotherapy for Difficult-to-Treat Brain Tumors with Gut Microbiota

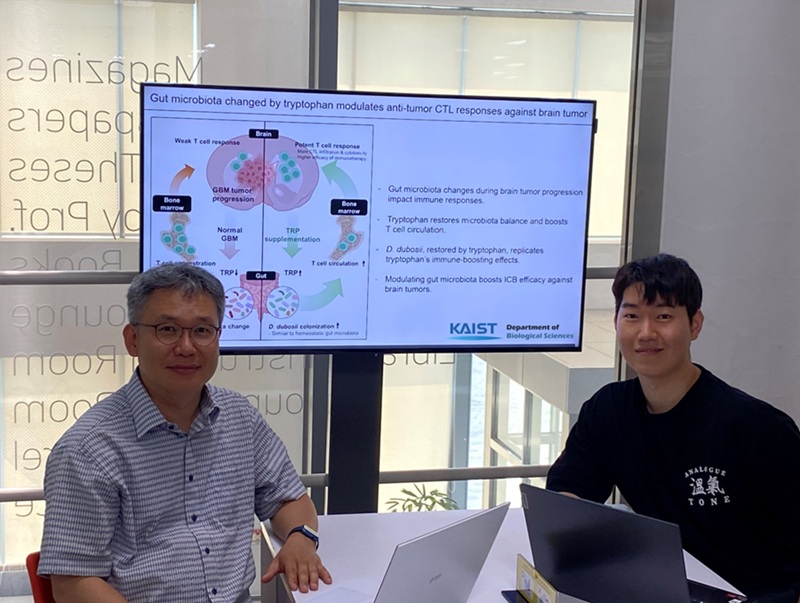

< Photo 1.(From left) Prof. Heung Kyu Lee, Department of Biological Sciences,

and Dr. Hyeon Cheol Kim>

Advanced treatments, known as immunotherapies that activate T cells—our body's immune cells—to eliminate cancer cells, have shown limited efficacy as standalone therapies for glioblastoma, the most lethal form of brain tumor. This is due to their minimal response to glioblastoma and high resistance to treatment.

Now, a KAIST research team has now demonstrated a new therapeutic strategy that can enhance the efficacy of immunotherapy for brain tumors by utilizing gut microbes and their metabolites. This also opens up possibilities for developing microbiome-based immunotherapy supplements in the future.

KAIST (President Kwang Hyung Lee) announced on July 1 that a research team led by Professor Heung Kyu Lee of the Department of Biological Sciences discovered and demonstrated a method to significantly improve the efficiency of glioblastoma immunotherapy by focusing on changes in the gut microbial ecosystem.

The research team noted that as glioblastoma progresses, the concentration of ‘tryptophan’, an important amino acid in the gut, sharply decreases, leading to changes in the gut microbial ecosystem. They discovered that by supplementing tryptophan to restore microbial diversity, specific beneficial strains activate CD8 T cells (a type of immune cell) and induce their infiltration into tumor tissues. Through a mouse model of glioblastoma, the research team confirmed that tryptophan supplementation enhanced the response of cancer-attacking T cells (especially CD8 T cells), leading to their increased migration to tumor sites such as lymph nodes and the brain.

In this process, they also revealed that ‘Duncaniella dubosii’, a beneficial commensal bacterium present in the gut, plays a crucial role. This bacterium helped T cells effectively redistribute within the body, and survival rates significantly improved when used in combination with immunotherapy (anti-PD-1).

Furthermore, it was demonstrated that even when this commensal bacterium was administered alone to germ-free mice (mice without any commensal microbes), the survival rate for glioblastoma increased. This is because the bacterium utilizes tryptophan to regulate the gut environment, and the metabolites produced in this process strengthen the ability of CD8 T cells to attack cancer cells.

Professor Heung Kyu Lee explained, "This research is a meaningful achievement, showing that even in intractable brain tumors where immune checkpoint inhibitors had no effect, a combined strategy utilizing gut microbes can significantly enhance treatment response."

Dr. Hyeon Cheol Kim of KAIST (currently a postdoctoral researcher at the Institute for Biological Sciences) participated as the first author. The research findings were published online in Cell Reports, an international journal in the life sciences, on June 26.

This research was conducted as part of the Basic Research Program and Bio & Medical Technology Development Program supported by the Ministry of Science and ICT and the National Research Foundation of Korea.

※Paper Title: Gut microbiota dysbiosis induced by brain tumor modulates the efficacy of immunotherapy

※DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2025.115825

2025.07.02 View 1013

KAIST Enhances Immunotherapy for Difficult-to-Treat Brain Tumors with Gut Microbiota

< Photo 1.(From left) Prof. Heung Kyu Lee, Department of Biological Sciences,

and Dr. Hyeon Cheol Kim>

Advanced treatments, known as immunotherapies that activate T cells—our body's immune cells—to eliminate cancer cells, have shown limited efficacy as standalone therapies for glioblastoma, the most lethal form of brain tumor. This is due to their minimal response to glioblastoma and high resistance to treatment.

Now, a KAIST research team has now demonstrated a new therapeutic strategy that can enhance the efficacy of immunotherapy for brain tumors by utilizing gut microbes and their metabolites. This also opens up possibilities for developing microbiome-based immunotherapy supplements in the future.

KAIST (President Kwang Hyung Lee) announced on July 1 that a research team led by Professor Heung Kyu Lee of the Department of Biological Sciences discovered and demonstrated a method to significantly improve the efficiency of glioblastoma immunotherapy by focusing on changes in the gut microbial ecosystem.

The research team noted that as glioblastoma progresses, the concentration of ‘tryptophan’, an important amino acid in the gut, sharply decreases, leading to changes in the gut microbial ecosystem. They discovered that by supplementing tryptophan to restore microbial diversity, specific beneficial strains activate CD8 T cells (a type of immune cell) and induce their infiltration into tumor tissues. Through a mouse model of glioblastoma, the research team confirmed that tryptophan supplementation enhanced the response of cancer-attacking T cells (especially CD8 T cells), leading to their increased migration to tumor sites such as lymph nodes and the brain.

In this process, they also revealed that ‘Duncaniella dubosii’, a beneficial commensal bacterium present in the gut, plays a crucial role. This bacterium helped T cells effectively redistribute within the body, and survival rates significantly improved when used in combination with immunotherapy (anti-PD-1).

Furthermore, it was demonstrated that even when this commensal bacterium was administered alone to germ-free mice (mice without any commensal microbes), the survival rate for glioblastoma increased. This is because the bacterium utilizes tryptophan to regulate the gut environment, and the metabolites produced in this process strengthen the ability of CD8 T cells to attack cancer cells.

Professor Heung Kyu Lee explained, "This research is a meaningful achievement, showing that even in intractable brain tumors where immune checkpoint inhibitors had no effect, a combined strategy utilizing gut microbes can significantly enhance treatment response."

Dr. Hyeon Cheol Kim of KAIST (currently a postdoctoral researcher at the Institute for Biological Sciences) participated as the first author. The research findings were published online in Cell Reports, an international journal in the life sciences, on June 26.

This research was conducted as part of the Basic Research Program and Bio & Medical Technology Development Program supported by the Ministry of Science and ICT and the National Research Foundation of Korea.

※Paper Title: Gut microbiota dysbiosis induced by brain tumor modulates the efficacy of immunotherapy

※DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2025.115825

2025.07.02 View 1013 -

KAIST develops technology for selective RNA modification in living cells and animals

· A team led by Professor Won Do Heo from the Department of Biological Sciences, KAIST, has developed a pioneering technology that selectively acetylates specific RNA molecules in living cells and tissues.

· The platform uses RNA-targeting CRISPR tools in combination with RNA-modifying enzymes to chemically modify only the intended RNA.

· The method opens new possibilities for gene therapy by enabling precise control of disease-related RNA without affecting the rest of the transcriptome.

< Photo 1. (From left) Professor Won Do Heo and Jihwan Yu, a Ph.D. Candidate of the Department of Biological Sciences >

CRISPR-Cas13, a powerful RNA-targeting technology is gaining increasing attention as a next-generation gene therapy platform due to its precision and reduced side effects. Utilizing this system, researchers at KAIST have now developed the world’s first technology capable of selectively acetylating (chemically modifying) specific RNA molecules among countless transcripts within living cells. This breakthrough enables precise, programmable control of RNA function and is expected to open new avenues in RNA-based therapeutic development.

KAIST (President Kwang Hyung Lee) announced that a research team led by Professor Won Do Heo in the Department of Biological Sciences has recently developed a groundbreaking technology capable of selectively acetylating specific RNA molecules within the human body using the CRISPR-Cas13 system—an RNA-targeting platform gaining increasing attention in the fields of gene regulation and RNA-based therapeutics.

RNA molecules can undergo chemical modifications—the addition of specific chemical groups—which alter their function and behavior without changing the underlying nucleotide sequence. However, some of these modifications, a critical layer of post-transcriptional gene regulation, remain poorly understood. Among them, N4-acetylcytidine (ac4C) has been particularly enigmatic, with ongoing debate about its existence and function in human messenger RNA (mRNA), the RNA that encodes proteins.

To address this gap, the KAIST research team developed a targeted RNA acetylation system, named dCas13-eNAT10. This platform combines a catalytically inactive Cas13 enzyme (dCas13) that guides the system to specific RNA targets, with a hyperactive variant of the NAT10 enzyme (eNAT10), which performs RNA acetylation. This approach enables precise acetylation of only the desired RNA molecules among the vast pool of transcripts within the cell.

< Figure 1. Development of hyperactive variant eNAT10 through NAT10 protein engineering. By engineering the NAT10 protein, which performs RNA acetylation in human cells, based on its domain and structure, eNAT10 was developed, showing approximately a 3-fold increase in RNA acetylation activity compared to the wild-type enzyme. >

Using this system, the researchers demonstrated that guide RNAs could direct the dCas13-eNAT10 complex to acetylate specific RNA targets, and acetylation significantly increased protein expression from the modified mRNA. Moreover, the study revealed, for the first time, that RNA acetylation plays a role in intracellular RNA localization, facilitating the export of RNA from the nucleus to the cytoplasm—a critical step in gene expression regulation.

To validate its therapeutic potential, the team successfully delivered the targeted RNA acetylation system into the livers of live mice using adeno-associated virus (AAV), a commonly used gene therapy vector. This marks the first demonstration of in vivo RNA modification, extending the applicability of RNA chemical modification tools from cell culture models to living organisms.

< Figure 2. Acetylation of various RNA in cells using dCas13-eNAT10 fusion protein. Utilizing the CRISPR-Cas13 system, which can precisely target specific RNA through guide RNA, a dCas13-eNAT10 fusion protein was created, demonstrating its ability to specifically acetylate various endogenous RNA at different locations within cells. >

Professor Won Do Heo, who previously developed COVID-19 treatment technology using RNA gene scissors and technology to activate RNA gene scissors with light, stated, "Existing RNA chemical modification research faced difficulties in controlling specificity, temporality, and spatiality. However, this new technology allows selective acetylation of desired RNA, opening the door for accurate and detailed research into the functions of RNA acetylation." He added, "The RNA chemical modification technology developed in this study can be widely used as an RNA-based therapeutic agent and a tool for regulating RNA functions in living organisms in the future."

< Figure 3. In vivo delivery of targeted RNA acetylation system. The targeted RNA acetylation system was encoded in an AAV vector, commonly used in gene therapy, and delivered intravenously to adult mice, showing that target RNA in liver tissue was specifically acetylated according to the guide RNA. >

This research, with Ph.D. candidate Jihwan Yu from the Department of Biological Sciences at KAIST as the first author, was published in the journal Nature Chemical Biology on June 2, 2025. (Title: Programmable RNA acetylation with CRISPR-Cas13, Impact factor: 12.9, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41589-025-01922-3)

This research was supported by the Samsung Future Technology Foundation and the Bio & Medical Technology Development Program of the National Research Foundation of Korea.

2025.06.10 View 2076

KAIST develops technology for selective RNA modification in living cells and animals

· A team led by Professor Won Do Heo from the Department of Biological Sciences, KAIST, has developed a pioneering technology that selectively acetylates specific RNA molecules in living cells and tissues.

· The platform uses RNA-targeting CRISPR tools in combination with RNA-modifying enzymes to chemically modify only the intended RNA.

· The method opens new possibilities for gene therapy by enabling precise control of disease-related RNA without affecting the rest of the transcriptome.

< Photo 1. (From left) Professor Won Do Heo and Jihwan Yu, a Ph.D. Candidate of the Department of Biological Sciences >

CRISPR-Cas13, a powerful RNA-targeting technology is gaining increasing attention as a next-generation gene therapy platform due to its precision and reduced side effects. Utilizing this system, researchers at KAIST have now developed the world’s first technology capable of selectively acetylating (chemically modifying) specific RNA molecules among countless transcripts within living cells. This breakthrough enables precise, programmable control of RNA function and is expected to open new avenues in RNA-based therapeutic development.

KAIST (President Kwang Hyung Lee) announced that a research team led by Professor Won Do Heo in the Department of Biological Sciences has recently developed a groundbreaking technology capable of selectively acetylating specific RNA molecules within the human body using the CRISPR-Cas13 system—an RNA-targeting platform gaining increasing attention in the fields of gene regulation and RNA-based therapeutics.

RNA molecules can undergo chemical modifications—the addition of specific chemical groups—which alter their function and behavior without changing the underlying nucleotide sequence. However, some of these modifications, a critical layer of post-transcriptional gene regulation, remain poorly understood. Among them, N4-acetylcytidine (ac4C) has been particularly enigmatic, with ongoing debate about its existence and function in human messenger RNA (mRNA), the RNA that encodes proteins.

To address this gap, the KAIST research team developed a targeted RNA acetylation system, named dCas13-eNAT10. This platform combines a catalytically inactive Cas13 enzyme (dCas13) that guides the system to specific RNA targets, with a hyperactive variant of the NAT10 enzyme (eNAT10), which performs RNA acetylation. This approach enables precise acetylation of only the desired RNA molecules among the vast pool of transcripts within the cell.

< Figure 1. Development of hyperactive variant eNAT10 through NAT10 protein engineering. By engineering the NAT10 protein, which performs RNA acetylation in human cells, based on its domain and structure, eNAT10 was developed, showing approximately a 3-fold increase in RNA acetylation activity compared to the wild-type enzyme. >

Using this system, the researchers demonstrated that guide RNAs could direct the dCas13-eNAT10 complex to acetylate specific RNA targets, and acetylation significantly increased protein expression from the modified mRNA. Moreover, the study revealed, for the first time, that RNA acetylation plays a role in intracellular RNA localization, facilitating the export of RNA from the nucleus to the cytoplasm—a critical step in gene expression regulation.

To validate its therapeutic potential, the team successfully delivered the targeted RNA acetylation system into the livers of live mice using adeno-associated virus (AAV), a commonly used gene therapy vector. This marks the first demonstration of in vivo RNA modification, extending the applicability of RNA chemical modification tools from cell culture models to living organisms.

< Figure 2. Acetylation of various RNA in cells using dCas13-eNAT10 fusion protein. Utilizing the CRISPR-Cas13 system, which can precisely target specific RNA through guide RNA, a dCas13-eNAT10 fusion protein was created, demonstrating its ability to specifically acetylate various endogenous RNA at different locations within cells. >

Professor Won Do Heo, who previously developed COVID-19 treatment technology using RNA gene scissors and technology to activate RNA gene scissors with light, stated, "Existing RNA chemical modification research faced difficulties in controlling specificity, temporality, and spatiality. However, this new technology allows selective acetylation of desired RNA, opening the door for accurate and detailed research into the functions of RNA acetylation." He added, "The RNA chemical modification technology developed in this study can be widely used as an RNA-based therapeutic agent and a tool for regulating RNA functions in living organisms in the future."

< Figure 3. In vivo delivery of targeted RNA acetylation system. The targeted RNA acetylation system was encoded in an AAV vector, commonly used in gene therapy, and delivered intravenously to adult mice, showing that target RNA in liver tissue was specifically acetylated according to the guide RNA. >

This research, with Ph.D. candidate Jihwan Yu from the Department of Biological Sciences at KAIST as the first author, was published in the journal Nature Chemical Biology on June 2, 2025. (Title: Programmable RNA acetylation with CRISPR-Cas13, Impact factor: 12.9, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41589-025-01922-3)

This research was supported by the Samsung Future Technology Foundation and the Bio & Medical Technology Development Program of the National Research Foundation of Korea.

2025.06.10 View 2076 -

A 10-Month Journey of Tiny Flaps Completed: A Special Family Returns to KAIST Duck Pond

On the morning of June 9, 2025, gentle activity stirred early around the KAIST campus duck pond. It was the day a special family of ducks—and two goslings—were to be released back into the pond after spending a month in a temporary shelter. One by one, the ducklings cautiously emerged from their box, waddling toward the water's edge and scanning their surroundings, followed closely by their mother.

< The landscape manager from the KAIST Facilities Team releases the ducks and goslings. >

The mother duck, once a rescued loner who couldn’t integrate with the flock, returned triumphantly as the head of a new family—caring for both ducklings and goslings. Students and faculty looked on quietly, welcoming them back and reflecting on their remarkable 10-month journey.

The story began in July 2024, as a student filed a report of spotting two ducklings wandering near the pond without a mother. Based on their soft down, flat beaks, and lack of fear around humans, it was presumed they had been abandoned. Professor Won Do Heo of the Department of Biological Sciences—affectionately known as the “Goose Dad”—and the KAIST Facilities Team quickly stepped in to rescue them. After about a month of care, the ducklings were released back into the pond.

< On June 9, the day of the release, KAIST President Kwang-Hyung Lee (left), the former “Goose Dad,” and Professor Won Do Heo (right), the current “Goose Dad,” watched the flock as they freely wobbled about. >

At first, the ducklings seemed to adapt, but they started distancing themselves from the established goose flock. One eventually disappeared, and the remaining duckling was found injured by the pond during winter. Although KAIST typically avoids making human interference in the natural ecosystem, an exception was made to save the young duck’s life. It was put under the care of Professor Heo and the Facilities Team to regain its health within a month.

In the spring, the healed duck began laying eggs. Professor Heo supported the process by adjusting its diet, avoiding further intervention. On Children’s Day, May 5, the duck’s eggs hatched. The once-isolated duck had become a mother. Ten days later, on May 15, four goslings also hatched from the resident goose flock. With new life flourishing, the pond was more vibrant than ever.

< Rescued baby goslings near the pond, alongside the duck family that took them in. The mother duck—once a vulnerable duckling herself—had grown strong enough to care for others in need. >

But just days later, the mother goose disappeared, and two goslings—still unable to swim—were found shivering by the pond. Dahyeon Byeon, a student from Seoul National University who came for a visit on that day, reported this upon sighting, prompting another rescue. The vulnerable goslings were brought to the shelter to stay with the duck family.

Initially, the interspecies cohabitation was uneasy. But the mother duck did not reject the goslings. Slowly, they began to eat and sleep together, forming a new kind of family. After a month, they were released together into the pond—and to everyone’s surprise, the existing goose flock accepted both the goslings and the duck family.

< A peaceful moment for the duck family. The baby goslings naturally followed the mother duck. >

It took ten months for this family to return. From abandonment and injury to healing, birth, and unexpected bonds, this was more than a story of survival. It was a journey of transformation. The duck family’s ten-month saga is a quiet miracle—written in small moments of crisis, care, and connection—and a lasting memory on the KAIST campus.

< The resident goose flock at KAIST’s pond naturally accepted the returning duck and goslings as part of their group. >

2025.06.10 View 2159

A 10-Month Journey of Tiny Flaps Completed: A Special Family Returns to KAIST Duck Pond

On the morning of June 9, 2025, gentle activity stirred early around the KAIST campus duck pond. It was the day a special family of ducks—and two goslings—were to be released back into the pond after spending a month in a temporary shelter. One by one, the ducklings cautiously emerged from their box, waddling toward the water's edge and scanning their surroundings, followed closely by their mother.

< The landscape manager from the KAIST Facilities Team releases the ducks and goslings. >

The mother duck, once a rescued loner who couldn’t integrate with the flock, returned triumphantly as the head of a new family—caring for both ducklings and goslings. Students and faculty looked on quietly, welcoming them back and reflecting on their remarkable 10-month journey.

The story began in July 2024, as a student filed a report of spotting two ducklings wandering near the pond without a mother. Based on their soft down, flat beaks, and lack of fear around humans, it was presumed they had been abandoned. Professor Won Do Heo of the Department of Biological Sciences—affectionately known as the “Goose Dad”—and the KAIST Facilities Team quickly stepped in to rescue them. After about a month of care, the ducklings were released back into the pond.

< On June 9, the day of the release, KAIST President Kwang-Hyung Lee (left), the former “Goose Dad,” and Professor Won Do Heo (right), the current “Goose Dad,” watched the flock as they freely wobbled about. >

At first, the ducklings seemed to adapt, but they started distancing themselves from the established goose flock. One eventually disappeared, and the remaining duckling was found injured by the pond during winter. Although KAIST typically avoids making human interference in the natural ecosystem, an exception was made to save the young duck’s life. It was put under the care of Professor Heo and the Facilities Team to regain its health within a month.

In the spring, the healed duck began laying eggs. Professor Heo supported the process by adjusting its diet, avoiding further intervention. On Children’s Day, May 5, the duck’s eggs hatched. The once-isolated duck had become a mother. Ten days later, on May 15, four goslings also hatched from the resident goose flock. With new life flourishing, the pond was more vibrant than ever.

< Rescued baby goslings near the pond, alongside the duck family that took them in. The mother duck—once a vulnerable duckling herself—had grown strong enough to care for others in need. >

But just days later, the mother goose disappeared, and two goslings—still unable to swim—were found shivering by the pond. Dahyeon Byeon, a student from Seoul National University who came for a visit on that day, reported this upon sighting, prompting another rescue. The vulnerable goslings were brought to the shelter to stay with the duck family.

Initially, the interspecies cohabitation was uneasy. But the mother duck did not reject the goslings. Slowly, they began to eat and sleep together, forming a new kind of family. After a month, they were released together into the pond—and to everyone’s surprise, the existing goose flock accepted both the goslings and the duck family.

< A peaceful moment for the duck family. The baby goslings naturally followed the mother duck. >

It took ten months for this family to return. From abandonment and injury to healing, birth, and unexpected bonds, this was more than a story of survival. It was a journey of transformation. The duck family’s ten-month saga is a quiet miracle—written in small moments of crisis, care, and connection—and a lasting memory on the KAIST campus.

< The resident goose flock at KAIST’s pond naturally accepted the returning duck and goslings as part of their group. >

2025.06.10 View 2159 -

KAIST-UIUC researchers develop a treatment platform to disable the ‘biofilm’ shield of superbugs

< (From left) Ph.D. Candidate Joo Hun Lee (co-author), Professor Hyunjoon Kong (co-corresponding author) and Postdoctoral Researcher Yujin Ahn (co-first author) from the Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and Ju Yeon Chung (co-first author) from the Integrated Master's and Doctoral Program, and Professor Hyun Jung Chung (co-corresponding author) from the Department of Biological Sciences of KAIST >

A major cause of hospital-acquired infections, the super bacteria Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), not only exhibits strong resistance to existing antibiotics but also forms a dense biofilm that blocks the effects of external treatments. To meet this challenge, KAIST researchers, in collaboration with an international team, successfully developed a platform that utilizes microbubbles to deliver gene-targeted nanoparticles capable of break ing down the biofilms, offering an innovative solution for treating infections resistant to conventional antibiotics.

KAIST (represented by President Kwang Hyung Lee) announced on May 29 that a research team led by Professor Hyun Jung Chung from the Department of Biological Sciences, in collaboration with Professor Hyunjoon Kong's team at the University of Illinois, has developed a microbubble-based nano-gene delivery platform (BTN MB) that precisely delivers gene suppressors into bacteria to effectively remove biofilms formed by MRSA.

The research team first designed short DNA oligonucleotides that simultaneously suppress three major MRSA genes, related to—biofilm formation (icaA), cell division (ftsZ), and antibiotic resistance (mecA)—and engineered nanoparticles (BTN) to effectively deliver them into the bacteria.

< Figure 1. Effective biofilm treatment using biofilm-targeting nanoparticles controlled by microbubbler system. Schematic illustration of BTN delivery with microbubbles (MB), enabling effective permeation of ASOs targeting bacterial genes within biofilms infecting skin wounds. Gene silencing of targets involved in biofilm formation, bacterial proliferation, and antibiotic resistance leads to effective biofilm removal and antibacterial efficacy in vivo. >

In addition, microbubbles (MB) were used to increase the permeability of the microbial membrane, specifically the biofilm formed by MRSA. By combining these two technologies, the team implemented a dual-strike strategy that fundamentally blocks bacterial growth and prevents resistance acquisition.

This treatment system operates in two stages. First, the MBs induce pressure changes within the bacterial biofilm, allowing the BTNs to penetrate. Then, the BTNs slip through the gaps in the biofilm and enter the bacteria, delivering the gene suppressors precisely. This leads to gene regulation within MRSA, simultaneously blocking biofilm regeneration, cell proliferation, and antibiotic resistance expression.

In experiments conducted in a porcine skin model and a mouse wound model infected with MRSA biofilm, the BTN MB treatment group showed a significant reduction in biofilm thickness, as well as remarkable decreases in bacterial count and inflammatory responses.

< Figure 2. (a) Schematic illustration on the evaluation of treatment efficacy of BTN-MB gene therapy. (b) Reduction in MRSA biofilm mass via simultaneous inhibition of multiple genes. (c, d) Antibacterial efficacy of BTN-MB over time in a porcine skin infection biofilm model. (e) Schematic of the experimental setup to verify antibacterial efficacy in a mouse skin wound infection model. (f) Wound healing effects in mice. (g) Antibacterial effects at the wound site. (h) Histological analysis results. >

These results are difficult to achieve with conventional antibiotic monotherapy and demonstrate the potential for treating a wide range of resistant bacterial infections.

Professor Hyun Jung Chung of KAIST, who led the research, stated, “This study presents a new therapeutic solution that combines nanotechnology, gene suppression, and physical delivery strategies to address superbug infections that existing antibiotics cannot resolve. We will continue our research with the aim of expanding its application to systemic infections and various other infectious diseases.”

< (From left) Ju Yeon Chung from the Integrated Master's and Doctoral Program, and Professor Hyun Jung Chung from the Department of Biological Sciences >

The study was co-first authored by Ju Yeon Chung, a graduate student in the Department of Biological Sciences at KAIST, and Dr. Yujin Ahn from the University of Illinois. The study was published online on May 19 in the journal, Advanced Functional Materials.

※ Paper Title: Microbubble-Controlled Delivery of Biofilm-Targeting Nanoparticles to Treat MRSA Infection ※ DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202508291

This study was supported by the National Research Foundation and the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea; and the National Science Foundation and National Institutes of Health, USA.

2025.05.29 View 3199

KAIST-UIUC researchers develop a treatment platform to disable the ‘biofilm’ shield of superbugs

< (From left) Ph.D. Candidate Joo Hun Lee (co-author), Professor Hyunjoon Kong (co-corresponding author) and Postdoctoral Researcher Yujin Ahn (co-first author) from the Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and Ju Yeon Chung (co-first author) from the Integrated Master's and Doctoral Program, and Professor Hyun Jung Chung (co-corresponding author) from the Department of Biological Sciences of KAIST >

A major cause of hospital-acquired infections, the super bacteria Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), not only exhibits strong resistance to existing antibiotics but also forms a dense biofilm that blocks the effects of external treatments. To meet this challenge, KAIST researchers, in collaboration with an international team, successfully developed a platform that utilizes microbubbles to deliver gene-targeted nanoparticles capable of break ing down the biofilms, offering an innovative solution for treating infections resistant to conventional antibiotics.

KAIST (represented by President Kwang Hyung Lee) announced on May 29 that a research team led by Professor Hyun Jung Chung from the Department of Biological Sciences, in collaboration with Professor Hyunjoon Kong's team at the University of Illinois, has developed a microbubble-based nano-gene delivery platform (BTN MB) that precisely delivers gene suppressors into bacteria to effectively remove biofilms formed by MRSA.

The research team first designed short DNA oligonucleotides that simultaneously suppress three major MRSA genes, related to—biofilm formation (icaA), cell division (ftsZ), and antibiotic resistance (mecA)—and engineered nanoparticles (BTN) to effectively deliver them into the bacteria.

< Figure 1. Effective biofilm treatment using biofilm-targeting nanoparticles controlled by microbubbler system. Schematic illustration of BTN delivery with microbubbles (MB), enabling effective permeation of ASOs targeting bacterial genes within biofilms infecting skin wounds. Gene silencing of targets involved in biofilm formation, bacterial proliferation, and antibiotic resistance leads to effective biofilm removal and antibacterial efficacy in vivo. >

In addition, microbubbles (MB) were used to increase the permeability of the microbial membrane, specifically the biofilm formed by MRSA. By combining these two technologies, the team implemented a dual-strike strategy that fundamentally blocks bacterial growth and prevents resistance acquisition.

This treatment system operates in two stages. First, the MBs induce pressure changes within the bacterial biofilm, allowing the BTNs to penetrate. Then, the BTNs slip through the gaps in the biofilm and enter the bacteria, delivering the gene suppressors precisely. This leads to gene regulation within MRSA, simultaneously blocking biofilm regeneration, cell proliferation, and antibiotic resistance expression.

In experiments conducted in a porcine skin model and a mouse wound model infected with MRSA biofilm, the BTN MB treatment group showed a significant reduction in biofilm thickness, as well as remarkable decreases in bacterial count and inflammatory responses.

< Figure 2. (a) Schematic illustration on the evaluation of treatment efficacy of BTN-MB gene therapy. (b) Reduction in MRSA biofilm mass via simultaneous inhibition of multiple genes. (c, d) Antibacterial efficacy of BTN-MB over time in a porcine skin infection biofilm model. (e) Schematic of the experimental setup to verify antibacterial efficacy in a mouse skin wound infection model. (f) Wound healing effects in mice. (g) Antibacterial effects at the wound site. (h) Histological analysis results. >

These results are difficult to achieve with conventional antibiotic monotherapy and demonstrate the potential for treating a wide range of resistant bacterial infections.

Professor Hyun Jung Chung of KAIST, who led the research, stated, “This study presents a new therapeutic solution that combines nanotechnology, gene suppression, and physical delivery strategies to address superbug infections that existing antibiotics cannot resolve. We will continue our research with the aim of expanding its application to systemic infections and various other infectious diseases.”

< (From left) Ju Yeon Chung from the Integrated Master's and Doctoral Program, and Professor Hyun Jung Chung from the Department of Biological Sciences >

The study was co-first authored by Ju Yeon Chung, a graduate student in the Department of Biological Sciences at KAIST, and Dr. Yujin Ahn from the University of Illinois. The study was published online on May 19 in the journal, Advanced Functional Materials.

※ Paper Title: Microbubble-Controlled Delivery of Biofilm-Targeting Nanoparticles to Treat MRSA Infection ※ DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202508291

This study was supported by the National Research Foundation and the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea; and the National Science Foundation and National Institutes of Health, USA.

2025.05.29 View 3199 -

Life Springs at KAIST: A Tale of Two Special Campus Families

A Gift of Life on Teachers' Day: Baby Geese Born at KAIST Pond

On Teachers' Day, a meaningful miracle of life arrived at the KAIST campus. A pair of geese gave birth to two goslings by the duck pond.

< On Teachers' Day, a pair of geese and their goslings leisurely swim in the pond. >

The baby goslings, covered in yellow down, began exploring the pond's edge, scurrying about, while their aunt geese steadfastly stood by. Their curious glances, watchful gazes, playful hops on waterside rocks, and the procession of babies swimming behind their parents in the water melted the hearts of onlookers.

< As night falls on the duck pond, the goose family gathers among the reeds. >

This special new life, born on Teachers' Day, seems to symbolize the day's meaning of "care" and "growth." This wondrous scene of life brought warm comfort and joy to KAIST members, adding the inspiration of nature to a campus that is a space for research and learning.

< Under the protection of the adult geese, the goslings take their first steps, exploring the pond's grassy areas and rocks. >

This adorable family is already roaming the area leisurely, like the pond's owners. With the joy of life added to the spring-filled pond, warm smiles are spreading across the KAIST campus.

< The geese look around, surveying their surroundings, while caring for their goslings. >

The pond has now become a small but special haven for students and staff. This goose family, arriving on Teachers' Day, quietly reminds us of the meaning of care and learning conveyed by nature.

< The goose family shows care and growth, and warm moments together are anticipated. >

---

On Children's Day 2025, a Duck Becomes a Mother

In July 2024, a special guest arrived at the KAIST campus. With soft yellow down, waddling gait, and a flat beak, it was undeniably a baby duck. However, for some reason, its mother was nowhere to be seen. Given that it wasn't afraid of people and followed them well, it was clear that someone had abandoned the duck.

Fortunately, the baby duck was safely rescued thanks to prompt reporting by students.

< Two ducks found on a corner of campus, immediately after their rescue in summer 2024. >

The ducks, newly integrated into KAIST, seemed to adapt relatively peacefully to campus life. As new additions, they couldn't blend in with the existing goose flock that had settled on campus, but the geese didn't ostracize them either. Perhaps because they were awkward neighbors, there was hope that the ducks would soon join the existing goose flock.

< Following their rescue based on a student's report in summer 2024, the ducks adapted to campus life under the protection of the campus facility team and Professor Won Do Heo. >

Professor Won Do Heo of the Department of Biological Sciences, widely known as "Goose Dad," stepped forward to protect them along with the KAIST facility team. Professor Heo is well-known for consistently observing and protecting the campus geese and ducks, which are practically symbols of KAIST. Thanks to the care of the staff and Professor Heo, the two ducks were safely released back onto campus approximately one month after their rescue.

< A moment on campus: Before winter, the ducks lived separately from the goose flock, maintaining a certain distance. While there were no conflicts, they rarely socialized. >

However, as winter passed, sad news arrived. One duck went missing, and the remaining one was found injured by the pond. While the policy of the facility team and Professor Heo was to minimize intervention to allow campus animals to maintain their natural state, saving the injured duck was the top priority. After being isolated again for a month of recovery, the duck fully recovered and was able to greet spring under the sun.

< The mother duck left alone in winter: One went missing, and the remaining one was found injured. After indoor isolation and recovery, she was released back onto campus in the spring. >

As spring, the ducks' breeding season, began, Professor Heo decided to offer a little more help. When signs of egg-laying appeared, he consistently provided "special meals for pregnant mothers" throughout March. On the morning of May 5th, Children's Day, 28 days after the mother duck began incubating her eggs with the care and attention of KAIST members, new life finally hatched. It was a precious outcome achieved solely by the duck that had survived abandonment and injury, with no special protection other than food.

The duck, having overcome hardship and injury to stand alone, has now formed a new family. Although there is still some distance from the existing goose flock, it is expected that they will naturally find their place in the campus ecosystem, as KAIST's geese are not aggressive or exclusive. The KAIST goose flock already has experience protecting and raising five ducklings.

< A new beginning by the pond on Children's Day: On the morning of May 5th, the 28th day of incubation, four ducklings hatched by the pond. This was a natural hatching, achieved without protective equipment. >

A single duck brought a special spring to the KAIST campus on Children's Day. The outcome achieved by that small life, leading to the birth of a new family, also symbolizes the harmonious coexistence of people and animals on the KAIST campus. The careful intervention of KAIST members, providing only the necessary assistance from rescue to hatching, makes us reconsider what "desirable coexistence between animals and people" truly means.

2025.05.21 View 3448

Life Springs at KAIST: A Tale of Two Special Campus Families

A Gift of Life on Teachers' Day: Baby Geese Born at KAIST Pond

On Teachers' Day, a meaningful miracle of life arrived at the KAIST campus. A pair of geese gave birth to two goslings by the duck pond.

< On Teachers' Day, a pair of geese and their goslings leisurely swim in the pond. >

The baby goslings, covered in yellow down, began exploring the pond's edge, scurrying about, while their aunt geese steadfastly stood by. Their curious glances, watchful gazes, playful hops on waterside rocks, and the procession of babies swimming behind their parents in the water melted the hearts of onlookers.

< As night falls on the duck pond, the goose family gathers among the reeds. >

This special new life, born on Teachers' Day, seems to symbolize the day's meaning of "care" and "growth." This wondrous scene of life brought warm comfort and joy to KAIST members, adding the inspiration of nature to a campus that is a space for research and learning.

< Under the protection of the adult geese, the goslings take their first steps, exploring the pond's grassy areas and rocks. >

This adorable family is already roaming the area leisurely, like the pond's owners. With the joy of life added to the spring-filled pond, warm smiles are spreading across the KAIST campus.

< The geese look around, surveying their surroundings, while caring for their goslings. >

The pond has now become a small but special haven for students and staff. This goose family, arriving on Teachers' Day, quietly reminds us of the meaning of care and learning conveyed by nature.

< The goose family shows care and growth, and warm moments together are anticipated. >

---

On Children's Day 2025, a Duck Becomes a Mother

In July 2024, a special guest arrived at the KAIST campus. With soft yellow down, waddling gait, and a flat beak, it was undeniably a baby duck. However, for some reason, its mother was nowhere to be seen. Given that it wasn't afraid of people and followed them well, it was clear that someone had abandoned the duck.

Fortunately, the baby duck was safely rescued thanks to prompt reporting by students.

< Two ducks found on a corner of campus, immediately after their rescue in summer 2024. >

The ducks, newly integrated into KAIST, seemed to adapt relatively peacefully to campus life. As new additions, they couldn't blend in with the existing goose flock that had settled on campus, but the geese didn't ostracize them either. Perhaps because they were awkward neighbors, there was hope that the ducks would soon join the existing goose flock.

< Following their rescue based on a student's report in summer 2024, the ducks adapted to campus life under the protection of the campus facility team and Professor Won Do Heo. >

Professor Won Do Heo of the Department of Biological Sciences, widely known as "Goose Dad," stepped forward to protect them along with the KAIST facility team. Professor Heo is well-known for consistently observing and protecting the campus geese and ducks, which are practically symbols of KAIST. Thanks to the care of the staff and Professor Heo, the two ducks were safely released back onto campus approximately one month after their rescue.

< A moment on campus: Before winter, the ducks lived separately from the goose flock, maintaining a certain distance. While there were no conflicts, they rarely socialized. >

However, as winter passed, sad news arrived. One duck went missing, and the remaining one was found injured by the pond. While the policy of the facility team and Professor Heo was to minimize intervention to allow campus animals to maintain their natural state, saving the injured duck was the top priority. After being isolated again for a month of recovery, the duck fully recovered and was able to greet spring under the sun.

< The mother duck left alone in winter: One went missing, and the remaining one was found injured. After indoor isolation and recovery, she was released back onto campus in the spring. >

As spring, the ducks' breeding season, began, Professor Heo decided to offer a little more help. When signs of egg-laying appeared, he consistently provided "special meals for pregnant mothers" throughout March. On the morning of May 5th, Children's Day, 28 days after the mother duck began incubating her eggs with the care and attention of KAIST members, new life finally hatched. It was a precious outcome achieved solely by the duck that had survived abandonment and injury, with no special protection other than food.

The duck, having overcome hardship and injury to stand alone, has now formed a new family. Although there is still some distance from the existing goose flock, it is expected that they will naturally find their place in the campus ecosystem, as KAIST's geese are not aggressive or exclusive. The KAIST goose flock already has experience protecting and raising five ducklings.

< A new beginning by the pond on Children's Day: On the morning of May 5th, the 28th day of incubation, four ducklings hatched by the pond. This was a natural hatching, achieved without protective equipment. >

A single duck brought a special spring to the KAIST campus on Children's Day. The outcome achieved by that small life, leading to the birth of a new family, also symbolizes the harmonious coexistence of people and animals on the KAIST campus. The careful intervention of KAIST members, providing only the necessary assistance from rescue to hatching, makes us reconsider what "desirable coexistence between animals and people" truly means.

2025.05.21 View 3448 -

Decoding Fear: KAIST Identifies An Affective Brain Circuit Crucial for Fear Memory Formation by Non-nociceptive Threat Stimulus

Fear memories can form in the brain following exposure to threatening situations such as natural disasters, accidents, or violence. When these memories become excessive or distorted, they can lead to severe mental health disorders, including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety disorders, and depression. However, the mechanisms underlying fear memory formation triggered by affective pain rather than direct physical pain have remained largely unexplored – until now.

A KAIST research team has identified, for the first time, a brain circuit specifically responsible for forming fear memories in the absence of physical pain, marking a significant advance in understanding how psychological distress is processed and drives fear memory formation in the brain. This discovery opens the door to the development of targeted treatments for trauma-related conditions by addressing the underlying neural pathways.

< Photo 1. (from left) Professor Jin-Hee Han, Dr. Junho Han and Ph.D. Candidate Boin Suh of the Department of Biological Sciences >

KAIST (President Kwang-Hyung Lee) announced on May 15th that the research team led by Professor Jin-Hee Han in the Department of Biological Sciences has identified the pIC-PBN circuit*, a key neural pathway involved in forming fear memories triggered by psychological threats in the absence of sensory pain. This groundbreaking work was conducted through experiments with mice.*pIC–PBN circuit: A newly identified descending neural pathway from the posterior insular cortex (pIC) to the parabrachial nucleus (PBN), specialized for transmitting psychological threat information.

Traditionally, the lateral parabrachial nucleus (PBN) has been recognized as a critical part of the ascending pain pathway, receiving pain signals from the spinal cord. However, this study reveals a previously unknown role for the PBN in processing fear induced by non-painful psychological stimuli, fundamentally changing our understanding of its function in the brain.

This work is considered the first experimental evidence that 'emotional distress' and 'physical pain' are processed through different neural circuits to form fear memories, making it a significant contribution to the field of neuroscience. It clearly demonstrates the existence of a dedicated pathway (pIC-PBN) for transmitting emotional distress.

The study's first author, Dr. Junho Han, shared the personal motivation behind this research: “Our dog, Lego, is afraid of motorcycles. He never actually crashed into one, but ever since having a traumatizing event of having a motorbike almost run into him, just hearing the sound now triggers a fearful response. Humans react similarly – even if you didn’t have a personal experience of being involved in an accident, a near-miss or exposure to alarming media can create lasting fear memories, which may eventually lead to PTSD.”

He continued, “Until now, fear memory research has mainly relied on experimental models involving physical pain. However, much of real-world human fears arise from psychological threats, rather than from direct physical harm. Despite this, little was known about the brain circuits responsible for processing these psychological threats that can drive fear memory formation.”

To investigate this, the research team developed a novel fear conditioning model that utilizes visual threat stimuli instead of electrical shocks. In this model, mice were exposed to a rapidly expanding visual disk on a ceiling screen, simulating the threat of an approaching predator. This approach allowed the team to demonstrate that fear memories can form in response to a non-nociceptive, psychological threat alone, without the need for physical pain.

< Figure 1. Artificial activation of the posterior insular cortex (pIC) to lateral parabrachial nucleus (PBN) neural circuit induces anxiety-like behaviors and fear memory formation in mice. >

Using advanced chemogenetic and optogenetic techniques, the team precisely controlled neuronal activity, revealing that the lateral parabrachial nucleus (PBN) is essential to form fear memories in response to visual threats. They further traced the origin of these signals to the posterior insular cortex (pIC), a region known to process negative emotions and pain, confirming a direct connection between the two areas.

The study also showed that inhibiting the pIC–PBN circuit significantly reduced fear memory formation in response to visual threats, without affecting innate fear responses or physical pain-based learning. Conversely, artificially activating this circuit alone was sufficient to drive fear memory formation, confirming its role as a key pathway for processing psychological threat information.

< Figure 2. Schematic diagram of brain neural circuits transmitting emotional & physical pain threat signals. Visual threat stimuli do not involve physical pain but can create an anxious state and form fear memory through the affective pain signaling pathway. >

Professor Jin-Hee Han commented, “This study lays an important foundation for understanding how emotional distress-based mental disorders, such as PTSD, panic disorder, and anxiety disorder, develop, and opens new possibilities for targeted treatment approaches.”

The findings, authored by Dr. Junho Han (first author), Ph.D. candidate Boin Suh (second author), and Dr. Jin-Hee Han (corresponding author) of the Department of Biological Sciences, were published online in the international journal Science Advances on May 9, 2025.※ Paper Title: A top-down insular cortex circuit crucial for non-nociceptive fear learning. Science Advances (https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.10.14.618356)※ Author Information: Junho Han (first author), Boin Suh (second author), and Jin-Hee Han (corresponding author)

This research was supported by grants from the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2022M3E5E8081183 and NRF-2017M3C7A1031322).

2025.05.15 View 4038

Decoding Fear: KAIST Identifies An Affective Brain Circuit Crucial for Fear Memory Formation by Non-nociceptive Threat Stimulus

Fear memories can form in the brain following exposure to threatening situations such as natural disasters, accidents, or violence. When these memories become excessive or distorted, they can lead to severe mental health disorders, including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety disorders, and depression. However, the mechanisms underlying fear memory formation triggered by affective pain rather than direct physical pain have remained largely unexplored – until now.

A KAIST research team has identified, for the first time, a brain circuit specifically responsible for forming fear memories in the absence of physical pain, marking a significant advance in understanding how psychological distress is processed and drives fear memory formation in the brain. This discovery opens the door to the development of targeted treatments for trauma-related conditions by addressing the underlying neural pathways.

< Photo 1. (from left) Professor Jin-Hee Han, Dr. Junho Han and Ph.D. Candidate Boin Suh of the Department of Biological Sciences >

KAIST (President Kwang-Hyung Lee) announced on May 15th that the research team led by Professor Jin-Hee Han in the Department of Biological Sciences has identified the pIC-PBN circuit*, a key neural pathway involved in forming fear memories triggered by psychological threats in the absence of sensory pain. This groundbreaking work was conducted through experiments with mice.*pIC–PBN circuit: A newly identified descending neural pathway from the posterior insular cortex (pIC) to the parabrachial nucleus (PBN), specialized for transmitting psychological threat information.

Traditionally, the lateral parabrachial nucleus (PBN) has been recognized as a critical part of the ascending pain pathway, receiving pain signals from the spinal cord. However, this study reveals a previously unknown role for the PBN in processing fear induced by non-painful psychological stimuli, fundamentally changing our understanding of its function in the brain.

This work is considered the first experimental evidence that 'emotional distress' and 'physical pain' are processed through different neural circuits to form fear memories, making it a significant contribution to the field of neuroscience. It clearly demonstrates the existence of a dedicated pathway (pIC-PBN) for transmitting emotional distress.

The study's first author, Dr. Junho Han, shared the personal motivation behind this research: “Our dog, Lego, is afraid of motorcycles. He never actually crashed into one, but ever since having a traumatizing event of having a motorbike almost run into him, just hearing the sound now triggers a fearful response. Humans react similarly – even if you didn’t have a personal experience of being involved in an accident, a near-miss or exposure to alarming media can create lasting fear memories, which may eventually lead to PTSD.”

He continued, “Until now, fear memory research has mainly relied on experimental models involving physical pain. However, much of real-world human fears arise from psychological threats, rather than from direct physical harm. Despite this, little was known about the brain circuits responsible for processing these psychological threats that can drive fear memory formation.”

To investigate this, the research team developed a novel fear conditioning model that utilizes visual threat stimuli instead of electrical shocks. In this model, mice were exposed to a rapidly expanding visual disk on a ceiling screen, simulating the threat of an approaching predator. This approach allowed the team to demonstrate that fear memories can form in response to a non-nociceptive, psychological threat alone, without the need for physical pain.

< Figure 1. Artificial activation of the posterior insular cortex (pIC) to lateral parabrachial nucleus (PBN) neural circuit induces anxiety-like behaviors and fear memory formation in mice. >

Using advanced chemogenetic and optogenetic techniques, the team precisely controlled neuronal activity, revealing that the lateral parabrachial nucleus (PBN) is essential to form fear memories in response to visual threats. They further traced the origin of these signals to the posterior insular cortex (pIC), a region known to process negative emotions and pain, confirming a direct connection between the two areas.

The study also showed that inhibiting the pIC–PBN circuit significantly reduced fear memory formation in response to visual threats, without affecting innate fear responses or physical pain-based learning. Conversely, artificially activating this circuit alone was sufficient to drive fear memory formation, confirming its role as a key pathway for processing psychological threat information.

< Figure 2. Schematic diagram of brain neural circuits transmitting emotional & physical pain threat signals. Visual threat stimuli do not involve physical pain but can create an anxious state and form fear memory through the affective pain signaling pathway. >

Professor Jin-Hee Han commented, “This study lays an important foundation for understanding how emotional distress-based mental disorders, such as PTSD, panic disorder, and anxiety disorder, develop, and opens new possibilities for targeted treatment approaches.”

The findings, authored by Dr. Junho Han (first author), Ph.D. candidate Boin Suh (second author), and Dr. Jin-Hee Han (corresponding author) of the Department of Biological Sciences, were published online in the international journal Science Advances on May 9, 2025.※ Paper Title: A top-down insular cortex circuit crucial for non-nociceptive fear learning. Science Advances (https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.10.14.618356)※ Author Information: Junho Han (first author), Boin Suh (second author), and Jin-Hee Han (corresponding author)

This research was supported by grants from the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2022M3E5E8081183 and NRF-2017M3C7A1031322).

2025.05.15 View 4038 -

KAIST Develops Retinal Therapy to Restore Lost Vision

Vision is one of the most crucial human senses, yet over 300 million people worldwide are at risk of vision loss due to various retinal diseases. While recent advancements in retinal disease treatments have successfully slowed disease progression, no effective therapy has been developed to restore already lost vision—until now. KAIST researchers have successfully developed a novel drug to restore vision.

< Photo 1. (From left) Ph.D. candidate Museong Kim, Professor Jin Woo Kim, and Dr. Eun Jung Lee of KAIST Department of Biological Sciences >

KAIST (represented by President Kwang Hyung Lee) announced on the 30th of March that a research team led by Professor Jin Woo Kim from the Department of Biological Sciences has developed a treatment method that restores vision through retinal nerve regeneration.

The research team successfully induced retinal regeneration and vision recovery in a disease-model mouse by administering a compound that blocks the PROX1 (prospero homeobox 1) protein, which suppresses retinal regeneration. Furthermore, the effect lasted for more than six months.

This study marks the first successful induction of long-term neural regeneration in mammalian retinas, offering new hope to patients with degenerative retinal diseases who previously had no treatment options.

As the global population continues to age, the number of retinal disease patients is steadily increasing. However, no treatments exist to restore damaged retinas and vision. The primary reason for this is the mammalian retina's inability to regenerate once damaged.

Studies on cold-blooded animals, such as fish—known for their robust retinal regeneration—have shown that retinal injuries trigger Müller glia cells to dedifferentiate into retinal progenitor cells, which then generate new neurons. However, in mammals, this process is impaired, leading to permanent retinal damage.

< Figure 1. Schematic diagram of the mechanism of retinal regeneration through inhibition of PROX1 migration. PROX1 protein secreted from retinal damaged retinal neurons transfers to Müllerglia and inhibits dedifferentiation into neural progenitor cells and neural regeneration. When PROX1 is captured outside the cells by an antibody against PROX1 and its transfer to Müllerglia is interfered, dedifferentiation of Müllerglia cells and retinal regeneration processes are resumed, restoring visual function. >

Through this study, the research team identified the PROX1 protein as a key inhibitor of Müller glia dedifferentiation in mammals. PROX1 is a protein found in neurons of the retina, hippocampus, and spinal cord, where it suppresses neural stem cell proliferation and promotes differentiation into neurons.

The researchers discovered that PROX1 accumulates in damaged mouse retinal Müller glia, but is absent in the highly regenerative Müller glia of fish. Furthermore, they demonstrated that the PROX1 found in Müller glia is not synthesized internally but rather taken up from surrounding neurons, which fail to degrade and instead secrete the protein.

Based on this finding, the team developed a method to restore Müller glia’s regenerative ability by eliminating extracellular PROX1 before it reaches these cells.

< Figure 2. Retinal regeneration and visual recovery in a retinitis pigmentosa model mouse through Anti-PROX1 gene therapy. After administration of adeno-associated virus expressing PROX1 neutralizing antibodies (AAV2-Anti-PROX1) to the eyes of RP1 retinitis pigmentosa model mice with vision loss, the photoreceptor cell layer of the retina is restored (A) and vision is restored (B). >

This approach involves using an antibody that binds to PROX1, developed by Celliaz Inc., a biotech startup founded by Professor Jin Woo Kim’s research lab. When administered to disease-model mouse retinas, this antibody significantly promoted neural regeneration. Additionally, when delivered, the antibody gene to the retinas of retinitis pigmentosa disease model mice, it enabled sustained retinal regeneration and vision restoration for over six months.

The retinal regeneration-inducing therapy is currently being developed by Celliaz Inc. for application in various degenerative retinal diseases that currently lack effective treatments. The company aims to begin clinical trials by 2028.

This study was co-authored by Dr. Eun Jung Lee of Celliaz Inc. and Museong Kim, a Ph.D. candidate at KAIST, as joint first authors. The findings were published online on March 26 in the international journal Nature Communications. (Paper Title: Restoration of retinal regenerative potential of Müller glia by disrupting intercellular Prox1 transfer | DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-58290-8)

Dr. Eun Jung Lee stated, "We are about completing the optimization of the PROX1-neutralizing antibody (CLZ001) and move to preclinical studies before administering it to retinal disease patients. Our goal is to provide a solution for patients at risk of blindness who currently lack proper treatment options."

This research was supported by research funds from Korean National Research Foundation (NRF) and the Korea Drug Development Foundation (KDDF).

2025.03.31 View 14727

KAIST Develops Retinal Therapy to Restore Lost Vision

Vision is one of the most crucial human senses, yet over 300 million people worldwide are at risk of vision loss due to various retinal diseases. While recent advancements in retinal disease treatments have successfully slowed disease progression, no effective therapy has been developed to restore already lost vision—until now. KAIST researchers have successfully developed a novel drug to restore vision.

< Photo 1. (From left) Ph.D. candidate Museong Kim, Professor Jin Woo Kim, and Dr. Eun Jung Lee of KAIST Department of Biological Sciences >

KAIST (represented by President Kwang Hyung Lee) announced on the 30th of March that a research team led by Professor Jin Woo Kim from the Department of Biological Sciences has developed a treatment method that restores vision through retinal nerve regeneration.

The research team successfully induced retinal regeneration and vision recovery in a disease-model mouse by administering a compound that blocks the PROX1 (prospero homeobox 1) protein, which suppresses retinal regeneration. Furthermore, the effect lasted for more than six months.

This study marks the first successful induction of long-term neural regeneration in mammalian retinas, offering new hope to patients with degenerative retinal diseases who previously had no treatment options.

As the global population continues to age, the number of retinal disease patients is steadily increasing. However, no treatments exist to restore damaged retinas and vision. The primary reason for this is the mammalian retina's inability to regenerate once damaged.

Studies on cold-blooded animals, such as fish—known for their robust retinal regeneration—have shown that retinal injuries trigger Müller glia cells to dedifferentiate into retinal progenitor cells, which then generate new neurons. However, in mammals, this process is impaired, leading to permanent retinal damage.

< Figure 1. Schematic diagram of the mechanism of retinal regeneration through inhibition of PROX1 migration. PROX1 protein secreted from retinal damaged retinal neurons transfers to Müllerglia and inhibits dedifferentiation into neural progenitor cells and neural regeneration. When PROX1 is captured outside the cells by an antibody against PROX1 and its transfer to Müllerglia is interfered, dedifferentiation of Müllerglia cells and retinal regeneration processes are resumed, restoring visual function. >

Through this study, the research team identified the PROX1 protein as a key inhibitor of Müller glia dedifferentiation in mammals. PROX1 is a protein found in neurons of the retina, hippocampus, and spinal cord, where it suppresses neural stem cell proliferation and promotes differentiation into neurons.

The researchers discovered that PROX1 accumulates in damaged mouse retinal Müller glia, but is absent in the highly regenerative Müller glia of fish. Furthermore, they demonstrated that the PROX1 found in Müller glia is not synthesized internally but rather taken up from surrounding neurons, which fail to degrade and instead secrete the protein.

Based on this finding, the team developed a method to restore Müller glia’s regenerative ability by eliminating extracellular PROX1 before it reaches these cells.

< Figure 2. Retinal regeneration and visual recovery in a retinitis pigmentosa model mouse through Anti-PROX1 gene therapy. After administration of adeno-associated virus expressing PROX1 neutralizing antibodies (AAV2-Anti-PROX1) to the eyes of RP1 retinitis pigmentosa model mice with vision loss, the photoreceptor cell layer of the retina is restored (A) and vision is restored (B). >

This approach involves using an antibody that binds to PROX1, developed by Celliaz Inc., a biotech startup founded by Professor Jin Woo Kim’s research lab. When administered to disease-model mouse retinas, this antibody significantly promoted neural regeneration. Additionally, when delivered, the antibody gene to the retinas of retinitis pigmentosa disease model mice, it enabled sustained retinal regeneration and vision restoration for over six months.

The retinal regeneration-inducing therapy is currently being developed by Celliaz Inc. for application in various degenerative retinal diseases that currently lack effective treatments. The company aims to begin clinical trials by 2028.

This study was co-authored by Dr. Eun Jung Lee of Celliaz Inc. and Museong Kim, a Ph.D. candidate at KAIST, as joint first authors. The findings were published online on March 26 in the international journal Nature Communications. (Paper Title: Restoration of retinal regenerative potential of Müller glia by disrupting intercellular Prox1 transfer | DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-58290-8)

Dr. Eun Jung Lee stated, "We are about completing the optimization of the PROX1-neutralizing antibody (CLZ001) and move to preclinical studies before administering it to retinal disease patients. Our goal is to provide a solution for patients at risk of blindness who currently lack proper treatment options."

This research was supported by research funds from Korean National Research Foundation (NRF) and the Korea Drug Development Foundation (KDDF).

2025.03.31 View 14727 -

KAIST Uncovers the Principles of Gene Expression Regulation in Cancer and Cellular Functions

< (From left) Professor Seyun Kim, Professor Gwangrog Lee, Dr. Hyoungjoon Ahn, Dr. Jeongmin Yu, Professor Won-Ki Cho, and (below) PhD candidate Kwangmin Ryu of the Department of Biological Sciences>

A research team at KAIST has identified the core gene expression networks regulated by key proteins that fundamentally drive phenomena such as cancer development, metastasis, tissue differentiation from stem cells, and neural activation processes. This discovery lays the foundation for developing innovative therapeutic technologies.

On the 22nd of January, KAIST (represented by President Kwang Hyung Lee) announced that the joint research team led by Professors Seyun Kim, Gwangrog Lee, and Won-Ki Cho from the Department of Biological Sciences had uncovered essential mechanisms controlling gene expression in animal cells.

Inositol phosphate metabolites produced by inositol metabolism enzymes serve as vital secondary messengers in eukaryotic cell signaling systems and are broadly implicated in cancer, obesity, diabetes, and neurological disorders.

The research team demonstrated that the inositol polyphosphate multikinase (IPMK) enzyme, a key player in the inositol metabolism system, acts as a critical transcriptional activator within the core gene expression networks of animal cells. Notably, although IPMK was previously reported to play an important role in the transcription process governed by serum response factor (SRF), a representative transcription factor in animal cells, the precise mechanism of its action was unclear.

SRF is a transcription factor directly controlling the expression of at least 200–300 genes, regulating cell growth, proliferation, apoptosis, and motility, and is indispensable for organ development, such as in the heart.