Department+of+physics

-

A Hole in One for Holographic Display

(Professor YongKeun Park)

Researchers have designed an ultrathin display that can project dynamic, multi-coloured, 3D holographic images, according to a study published in Nature Communications.

The system’s critical component is a thin film of titanium filled with tiny holes that precisely correspond with each pixel in a liquid crystal display (LCD) panel. This film acts as a ‘photon sieve’ – each pinhole diffracts light emerging from them widely, resulting in a high-definition 3D image observable from a wide angle.

The entire system is very small: they used a 1.8-inch off-the-shelf LCD panel with a resolution of 1024 x 768. The titanium film, attached to the back of the panel, is a mere 300 nanometres thick.

“Our approach suggests that holographic displays could be projected from thin devices, like a cell phone,” says Professor YongKeun Park, a physicist at KAIST who led the research. The team demonstrated their approach by producing a hologram of a moving, tri-coloured cube.

Specifically, the images are made by pointing differently coloured laser beams made of parallel light rays at the small LCD panel. The photon sieve has a hole for each pixel in the LCD panel. The holes are precisely positioned to correspond to the pixel’s active area. The pinholes diffract the light emerging from them, producing 3D images.

Previous studies from Professor Park’s group have used optical diffusors for the same purpose, but the size of the device was bulky and difficult to be operated, and it took a long period of time to calibrate. In the present work, on the other hand, the group tailored their photon sieve to demonstrate a simple, compact and scalable method for 3D holographic display. This technique can be readily applied to existing LCD displays.

Applications for holograms have been limited by cumbersome techniques, high computation requirements, and poor image quality. Improving current techniques could lead to a wide variety of applications, including 3D cinema viewing without the need for glasses, watching holographic videos on television and smart phone screens.

Figure 1. The actual 3D holographic display, and an electron microscope image of the non-periodic pinholes.

Figure 2. Three-dimensional dynamic color hologram operating at 60 Hz

2019.04.18 View 33783

A Hole in One for Holographic Display

(Professor YongKeun Park)

Researchers have designed an ultrathin display that can project dynamic, multi-coloured, 3D holographic images, according to a study published in Nature Communications.

The system’s critical component is a thin film of titanium filled with tiny holes that precisely correspond with each pixel in a liquid crystal display (LCD) panel. This film acts as a ‘photon sieve’ – each pinhole diffracts light emerging from them widely, resulting in a high-definition 3D image observable from a wide angle.

The entire system is very small: they used a 1.8-inch off-the-shelf LCD panel with a resolution of 1024 x 768. The titanium film, attached to the back of the panel, is a mere 300 nanometres thick.

“Our approach suggests that holographic displays could be projected from thin devices, like a cell phone,” says Professor YongKeun Park, a physicist at KAIST who led the research. The team demonstrated their approach by producing a hologram of a moving, tri-coloured cube.

Specifically, the images are made by pointing differently coloured laser beams made of parallel light rays at the small LCD panel. The photon sieve has a hole for each pixel in the LCD panel. The holes are precisely positioned to correspond to the pixel’s active area. The pinholes diffract the light emerging from them, producing 3D images.

Previous studies from Professor Park’s group have used optical diffusors for the same purpose, but the size of the device was bulky and difficult to be operated, and it took a long period of time to calibrate. In the present work, on the other hand, the group tailored their photon sieve to demonstrate a simple, compact and scalable method for 3D holographic display. This technique can be readily applied to existing LCD displays.

Applications for holograms have been limited by cumbersome techniques, high computation requirements, and poor image quality. Improving current techniques could lead to a wide variety of applications, including 3D cinema viewing without the need for glasses, watching holographic videos on television and smart phone screens.

Figure 1. The actual 3D holographic display, and an electron microscope image of the non-periodic pinholes.

Figure 2. Three-dimensional dynamic color hologram operating at 60 Hz

2019.04.18 View 33783 -

Emeritus Professor JaeKwan Kim Makes Generous Gift

(From left: Dean of the Dept. Physics Eunseong Kim, Emeritus Professor JaeKwan Kim, KAIST President Sung-Chul Shin and Professor Soon Chil Lee)

Emeritus Professor JaeKwan Kim from the Department of Physics made a one hundred million won contribution to KAIST.

He joined KAIST in 1972 and for the next 25 years he dedicated himself to carrying out research and fostering students.

Professor Kim said, “It was a great pleasure and honor to dedicate myself to the development of KAIST as well as Korea. Although I only contributed a small amount of money, I hope that it will help to sustain the development of KAIST. I will continue to support the school behind the scenes.”

He also mentioned that it is meaningful to deliver this fund to KAIST President Sung-Chul Shin, who is the first alumnus president and also his former student.

President Shin said, “His warm heart towards his students will be a priceless gift for the development of KAIST. Not only the Department of Physics, but the entire school will need to work together to help us become a global value-creative leading university and contribute to the country and its people.”

2018.06.12 View 3801

Emeritus Professor JaeKwan Kim Makes Generous Gift

(From left: Dean of the Dept. Physics Eunseong Kim, Emeritus Professor JaeKwan Kim, KAIST President Sung-Chul Shin and Professor Soon Chil Lee)

Emeritus Professor JaeKwan Kim from the Department of Physics made a one hundred million won contribution to KAIST.

He joined KAIST in 1972 and for the next 25 years he dedicated himself to carrying out research and fostering students.

Professor Kim said, “It was a great pleasure and honor to dedicate myself to the development of KAIST as well as Korea. Although I only contributed a small amount of money, I hope that it will help to sustain the development of KAIST. I will continue to support the school behind the scenes.”

He also mentioned that it is meaningful to deliver this fund to KAIST President Sung-Chul Shin, who is the first alumnus president and also his former student.

President Shin said, “His warm heart towards his students will be a priceless gift for the development of KAIST. Not only the Department of Physics, but the entire school will need to work together to help us become a global value-creative leading university and contribute to the country and its people.”

2018.06.12 View 3801 -

KAIST Finds the Principle of Electric Wind in Plasma

(From left: Professor Wonho Choe and PhD Sanghoo Park)

A KAIST team identified the basic principle of electric wind in plasma. This finding will contribute to developing technology in various applications of plasma, including fluid control technology.

Professor Wonho Choe from the Department of Physics and his team identified the main principle of neutral gas flow in plasma, known as ‘electric wind’, in collaboration with Professor Se Youn Moon’s team at Chonbuk National University.

Electric wind in plasma is a well-known consequence of interactions arising from collisions between charged particles (electrons or ions) and neutral particles. It refers to the flow of neutral gas that occurs when charged particles accelerate and collide with a neutral gas.

This is a way to create air movement without mechanical movement, such as fan wings, and it is gaining interest as a next-generation technology to replace existing fans. However, there was no experimental evidence of the cause.

To identify the cause, the team used atmospheric pressure plasma. As a result, the team succeeded in identifying streamer propagation and space charge drift from electrohydrodynamic (EHD) force in a qualitative manner.

According to the team, streamer propagation has very little effect on electric wind, but space charge drift that follows streamer propagation and collapse was the main cause of electric wind.

The team also identified that electrons, instead of negatively charged ions, were key components of electric wind generation in certain plasmas.

Furthermore, electric wind with the highest speed of 4 m/s was created in a helium jet plasma, which is one fourth the speed of a typhoon. These results indicate that the study could provide basic principles to effectively control the speed of electric wind.

Professor Choe said, “These findings set a significant foundation to understand the interactions between electrons or ions and neutral particles that occur in weakly ionized plasmas, such as atmospheric pressure plasmas. This can play an important role in expanding the field of fluid-control applications using plasmas which becomes economically and commercially interest.”

This research, led by PhD Sanghoo Park, was published online in Nature Communications on January 25.

Figure 1. Plasma jet image

Figure 2. The differences in electric wind speeds and voltage pulse

2018.03.02 View 8597

KAIST Finds the Principle of Electric Wind in Plasma

(From left: Professor Wonho Choe and PhD Sanghoo Park)

A KAIST team identified the basic principle of electric wind in plasma. This finding will contribute to developing technology in various applications of plasma, including fluid control technology.

Professor Wonho Choe from the Department of Physics and his team identified the main principle of neutral gas flow in plasma, known as ‘electric wind’, in collaboration with Professor Se Youn Moon’s team at Chonbuk National University.

Electric wind in plasma is a well-known consequence of interactions arising from collisions between charged particles (electrons or ions) and neutral particles. It refers to the flow of neutral gas that occurs when charged particles accelerate and collide with a neutral gas.

This is a way to create air movement without mechanical movement, such as fan wings, and it is gaining interest as a next-generation technology to replace existing fans. However, there was no experimental evidence of the cause.

To identify the cause, the team used atmospheric pressure plasma. As a result, the team succeeded in identifying streamer propagation and space charge drift from electrohydrodynamic (EHD) force in a qualitative manner.

According to the team, streamer propagation has very little effect on electric wind, but space charge drift that follows streamer propagation and collapse was the main cause of electric wind.

The team also identified that electrons, instead of negatively charged ions, were key components of electric wind generation in certain plasmas.

Furthermore, electric wind with the highest speed of 4 m/s was created in a helium jet plasma, which is one fourth the speed of a typhoon. These results indicate that the study could provide basic principles to effectively control the speed of electric wind.

Professor Choe said, “These findings set a significant foundation to understand the interactions between electrons or ions and neutral particles that occur in weakly ionized plasmas, such as atmospheric pressure plasmas. This can play an important role in expanding the field of fluid-control applications using plasmas which becomes economically and commercially interest.”

This research, led by PhD Sanghoo Park, was published online in Nature Communications on January 25.

Figure 1. Plasma jet image

Figure 2. The differences in electric wind speeds and voltage pulse

2018.03.02 View 8597 -

KAIST to Develop Technology to Control Topological Defects

(Professor Chan-Ho Yang and PhD candidate Kwang-Eun Kim)

Professor Chan-Ho Yang and his team from the Department of Physics developed technology to create and remove topological defects in ferroelectric nanostructures.

This technology will contribute to developing topological defect-based storage that will allow the saving of massive amounts of information in a stable manner.

Topology refers to the property of matter upon deformation, in which a circle and a triangle are considered to be the same topologically.

During the announcement of the 2016 Nobel Prize in Physics, the concept of topology was explained with a bagel with a hole, cinnamon bread without a hole, and a glass cup. Although the cinnamon bread and the glass cup have different appearances, they are topologically the same since neither has a hole. In the same sense, the bagel and the cinnamon bread are topologically different.

In other words, topology of matter is conserved and its properties cannot be altered by continuous deformation.

Using this topological texture can produce information storage devices that can protect the stored information from external stimuli, but the data can still be written and erased, resulting in ideal non-volatile memory.

Unlike ferroelectrics, magnetic topological defect structures such as the ferromagnetic vortex and skyrmion have already been implemented.

Ferroelectrics, which have aligned electric dipoles without external electric fields, can stabilize topological defect structures to a smaller size using less energy; however, further research on ferroelectrics has not been carried out sufficiently. This is due to a lack of research on stabilizing topological defect structures and how to control them in an experimental setting.

To overcome this problem, the team applied inhomogeneous deformations to ferroelectric nanostructures to successfully stabilize the topological defect structures. The team manufactured a ferroelectric nanoplate structure on a special board, which can exert strong compression from the bottom surface while the sides and the upper surfaces of the structure is free from deformation.

This structure led to radial compressive strain relaxation, in which deformations of the lattice stabilize the vortex structure of ferroelectrics.

This could lead to the establishment of the core principle of topological ferroelectric memory of high density, high efficiency, and high stability.

Professor Yang said, “Ferroelectrics are nonconductor but topological ferroelectric quasiparticles could carry electrical conductivity locally. This finding could be expanded to new quantum device research.”

This research, led by the PhD candidate Kwang-Eun Kim, was published in Nature Communications on January 26.

The study was co-conducted by Professor Si-Young Choi and Dr. Tae Yeong Koo from POSTECH, Professor Long-Qing Chen from The Pennsylvania State University, and Professor Ramamoorthy Ramesh from the University of California at Berkeley.

Figure 1. Five different topological structures produced by controlling the number of topological defects

2018.02.19 View 8294

KAIST to Develop Technology to Control Topological Defects

(Professor Chan-Ho Yang and PhD candidate Kwang-Eun Kim)

Professor Chan-Ho Yang and his team from the Department of Physics developed technology to create and remove topological defects in ferroelectric nanostructures.

This technology will contribute to developing topological defect-based storage that will allow the saving of massive amounts of information in a stable manner.

Topology refers to the property of matter upon deformation, in which a circle and a triangle are considered to be the same topologically.

During the announcement of the 2016 Nobel Prize in Physics, the concept of topology was explained with a bagel with a hole, cinnamon bread without a hole, and a glass cup. Although the cinnamon bread and the glass cup have different appearances, they are topologically the same since neither has a hole. In the same sense, the bagel and the cinnamon bread are topologically different.

In other words, topology of matter is conserved and its properties cannot be altered by continuous deformation.

Using this topological texture can produce information storage devices that can protect the stored information from external stimuli, but the data can still be written and erased, resulting in ideal non-volatile memory.

Unlike ferroelectrics, magnetic topological defect structures such as the ferromagnetic vortex and skyrmion have already been implemented.

Ferroelectrics, which have aligned electric dipoles without external electric fields, can stabilize topological defect structures to a smaller size using less energy; however, further research on ferroelectrics has not been carried out sufficiently. This is due to a lack of research on stabilizing topological defect structures and how to control them in an experimental setting.

To overcome this problem, the team applied inhomogeneous deformations to ferroelectric nanostructures to successfully stabilize the topological defect structures. The team manufactured a ferroelectric nanoplate structure on a special board, which can exert strong compression from the bottom surface while the sides and the upper surfaces of the structure is free from deformation.

This structure led to radial compressive strain relaxation, in which deformations of the lattice stabilize the vortex structure of ferroelectrics.

This could lead to the establishment of the core principle of topological ferroelectric memory of high density, high efficiency, and high stability.

Professor Yang said, “Ferroelectrics are nonconductor but topological ferroelectric quasiparticles could carry electrical conductivity locally. This finding could be expanded to new quantum device research.”

This research, led by the PhD candidate Kwang-Eun Kim, was published in Nature Communications on January 26.

The study was co-conducted by Professor Si-Young Choi and Dr. Tae Yeong Koo from POSTECH, Professor Long-Qing Chen from The Pennsylvania State University, and Professor Ramamoorthy Ramesh from the University of California at Berkeley.

Figure 1. Five different topological structures produced by controlling the number of topological defects

2018.02.19 View 8294 -

Plasma, an Excellent Sterilizer to Remove Harmful Bacteria

(PhD candidate Joo Young Park, Professor Wonho Choe and PhD researcher Sanghoo Park)

KAIST researchers are using plasma to remove bacteria that are stuck to surfaces of plastic bottles and food. This novel technology will contribute to disinfection in medical settings as well as food and agricultural industries.

Professor Wonho Choe and his team from the Department of Physics developed a technology that removes biofilm, which is comprised of microorganisms, by using plasma as a non-thermal sterilization method.

Plasma contains multiple bactericidal agents, including reactive species. In particular, the chemicals formed in aqueous solution during plasma exposure have the potential for high antibacterial activity against various bacterial infections.

The team treated water with plasma to see how effectively bactericidal agents in the plasma water can remove biofilm comprised of harmful microorganism such as Escherichia coli, Salmonella, and Listeria.

The team identified that reactive species, including hydroxyl radical, hydrogen peroxide, ozone, nitrite, and superoxide produced during plasma treatment, showed considerable ability to remove the biofilm. Hydrogen peroxide showed the strongest effect removing the biofilm; however, the hydroxyl radical also played a significant role in removing biofilm. Despite having a concentration 100 to 10,000 times lower than other reactive species, the hydroxyl radical showed a high biofilm removal efficacy owing to its strong oxidative power.

These findings reveal that plasma can be used as a no-residual and safe sterilization process alternative to conventional methods. With these outcomes, the team is planning to develop and commercialize a technology that can produce hydroxyl radicals with plasma.

Professor Choe has registered a patent for flexible packaging materials that facilitate plasma and completed the technology transfer to the startup company, named ‘Plasmapp’, which focuses on commercializing bactericidal technology.

“This research outcome will be the foundation for understanding plasma control technology and physicochemical interactions between plasma and microorganisms. It will also become an accelerator for utilizing plasma technology in the medical, food, and agricultural fields,” said Professor Choe.

This research, led by PhD candidate Joo Young Park and PhD researcher Sanghoo Park in collaboration with Professor Cheorun Jo’s team from Seoul National University, was published in ACS Applied Materials and Interfaces on December 20, 2017.

Figure 1. Flexible packaging materials that facilitate plasma

Figure 2. Schematic diagram of biofilm treatment with plasma

Figure 3. Concept of plasma application and evaluation result of reactive species' efficacy

Figure 4. STERPACK, the product launched by Plasmapp

2018.01.25 View 10915

Plasma, an Excellent Sterilizer to Remove Harmful Bacteria

(PhD candidate Joo Young Park, Professor Wonho Choe and PhD researcher Sanghoo Park)

KAIST researchers are using plasma to remove bacteria that are stuck to surfaces of plastic bottles and food. This novel technology will contribute to disinfection in medical settings as well as food and agricultural industries.

Professor Wonho Choe and his team from the Department of Physics developed a technology that removes biofilm, which is comprised of microorganisms, by using plasma as a non-thermal sterilization method.

Plasma contains multiple bactericidal agents, including reactive species. In particular, the chemicals formed in aqueous solution during plasma exposure have the potential for high antibacterial activity against various bacterial infections.

The team treated water with plasma to see how effectively bactericidal agents in the plasma water can remove biofilm comprised of harmful microorganism such as Escherichia coli, Salmonella, and Listeria.

The team identified that reactive species, including hydroxyl radical, hydrogen peroxide, ozone, nitrite, and superoxide produced during plasma treatment, showed considerable ability to remove the biofilm. Hydrogen peroxide showed the strongest effect removing the biofilm; however, the hydroxyl radical also played a significant role in removing biofilm. Despite having a concentration 100 to 10,000 times lower than other reactive species, the hydroxyl radical showed a high biofilm removal efficacy owing to its strong oxidative power.

These findings reveal that plasma can be used as a no-residual and safe sterilization process alternative to conventional methods. With these outcomes, the team is planning to develop and commercialize a technology that can produce hydroxyl radicals with plasma.

Professor Choe has registered a patent for flexible packaging materials that facilitate plasma and completed the technology transfer to the startup company, named ‘Plasmapp’, which focuses on commercializing bactericidal technology.

“This research outcome will be the foundation for understanding plasma control technology and physicochemical interactions between plasma and microorganisms. It will also become an accelerator for utilizing plasma technology in the medical, food, and agricultural fields,” said Professor Choe.

This research, led by PhD candidate Joo Young Park and PhD researcher Sanghoo Park in collaboration with Professor Cheorun Jo’s team from Seoul National University, was published in ACS Applied Materials and Interfaces on December 20, 2017.

Figure 1. Flexible packaging materials that facilitate plasma

Figure 2. Schematic diagram of biofilm treatment with plasma

Figure 3. Concept of plasma application and evaluation result of reactive species' efficacy

Figure 4. STERPACK, the product launched by Plasmapp

2018.01.25 View 10915 -

Realizing Highly Efficient Quantum Dot LEDs with Metallic Nanostructures

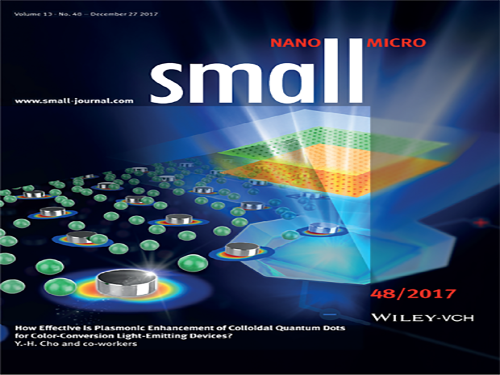

(Professor Yong-Hoon Cho and PhD candidate Hyun Chul Park)

KAIST researchers have discovered a technology that enhances the efficiency of Quantum Dot LEDs.

Professor Yong-Hoon Cho from the Department of Physics and his team succeeded in improving the efficiency of Quantum Dot (QD) Light-Emitting Diodes (LEDs) by designing metallic nanostructure substrates.

QD LEDs possess very small semiconductor light sources and are considered to be the new rising technology for high performance full-color display. However, it is expensive to manufacture displays with QD LED only.

Existing QD-based displays use blue LEDs as a source of light, and they employ a method of color conversion through excitation of green and red QDs.

There are two inconveniences with the existing QD-based displays. As mentioned previously, QD LED is costly, hence the unit price of QD-based displays is higher. Also, the efficiency of a liquid type of QDs is drastically lowered after contact with air.

Professor Cho found the solution in a metallic nanostructure for lowering the production cost while improving the efficiency of QD LEDs.

The team exploited the phenomenon of so-called surface plasmonic resonances when nanoscale metallic structures are exposed to light. Depending on the metal, the size, and the shape, the properties of metallic structures vary.

The team used different metallic nanostructures for each QD LED – silver nanodisks for Red QDs and aluminum nanodisks for Green GDs – to make them more fluorescent.

With brighter QDs, it requires fewer QDs to manufacture QD LEDs, contributing to a lower unit price.

The team used silver and aluminum in this research, but metallic nanostructures can be redesigned according to the desired purposes.

Professor Cho said, “Implementing metallic nanostructures into QD LEDs in a proper manner can reduce the quantity of the QDs required for the system, leading to lower unit prices.”

This research, led by PhD candidate Hyun Chul Park, was chosen as the cover of the international journal, Small, on December 27, 2017.

Figure 1. Cover of the journal

Figure 2. Spectrum showing different fluorescence with and without metallic nanostructure

2018.01.23 View 7703

Realizing Highly Efficient Quantum Dot LEDs with Metallic Nanostructures

(Professor Yong-Hoon Cho and PhD candidate Hyun Chul Park)

KAIST researchers have discovered a technology that enhances the efficiency of Quantum Dot LEDs.

Professor Yong-Hoon Cho from the Department of Physics and his team succeeded in improving the efficiency of Quantum Dot (QD) Light-Emitting Diodes (LEDs) by designing metallic nanostructure substrates.

QD LEDs possess very small semiconductor light sources and are considered to be the new rising technology for high performance full-color display. However, it is expensive to manufacture displays with QD LED only.

Existing QD-based displays use blue LEDs as a source of light, and they employ a method of color conversion through excitation of green and red QDs.

There are two inconveniences with the existing QD-based displays. As mentioned previously, QD LED is costly, hence the unit price of QD-based displays is higher. Also, the efficiency of a liquid type of QDs is drastically lowered after contact with air.

Professor Cho found the solution in a metallic nanostructure for lowering the production cost while improving the efficiency of QD LEDs.

The team exploited the phenomenon of so-called surface plasmonic resonances when nanoscale metallic structures are exposed to light. Depending on the metal, the size, and the shape, the properties of metallic structures vary.

The team used different metallic nanostructures for each QD LED – silver nanodisks for Red QDs and aluminum nanodisks for Green GDs – to make them more fluorescent.

With brighter QDs, it requires fewer QDs to manufacture QD LEDs, contributing to a lower unit price.

The team used silver and aluminum in this research, but metallic nanostructures can be redesigned according to the desired purposes.

Professor Cho said, “Implementing metallic nanostructures into QD LEDs in a proper manner can reduce the quantity of the QDs required for the system, leading to lower unit prices.”

This research, led by PhD candidate Hyun Chul Park, was chosen as the cover of the international journal, Small, on December 27, 2017.

Figure 1. Cover of the journal

Figure 2. Spectrum showing different fluorescence with and without metallic nanostructure

2018.01.23 View 7703 -

Controlling Superconductivity Using Spin Currents

(Professor Jhinhwan Lee and Dr. Seokhwan Choi)

A KAIST research team led by Professor Jhinhwan Lee of the Department of Physics has discovered a method to flip between superconducting and non-superconducting states within an iron-based superconductor using a type of electron microscopy. The team applied spin-polarized and non-polarized currents to locally change the magnetic order in the sample.

The team identified a basic physical principle required to develop transistors that control superconductivity and to implement novel magnetic memory at the atomic level. This study is the first report of a direct real-space observation of this type of control. In addition, this is the first direct atomic-scale demonstration of the correlation between magnetism and superconductivity.

The team controlled and observed the magnetic and electronic properties with a spin-polarized scanning tunneling microscope (SPSTM), a device that passes an atomically-sharp metal tip over the surface of a sample. The team introduced new ways to perform SPSTM using an antiferromagnetic chromium tip. An antiferromagnet is a material in which the magnetic fields of its atoms are ordered in an alternating up-down pattern such that it has a minimal stray magnetic field that can inadvertently kill the local superconductivity of the sample when used as an SPSTM tip.

To study the connection between the C4 magnetic order and the suppression of superconductivity, the team performed high-resolution SPSTM scans of the C4 state with chromium tips and compared them with simulations. The results led them to suggest that the low-energy spin fluctuations in the C4 state cannot mediate pairing between electrons in the typical FeAs band structure. This is critical because this paring of electrons, defying their natural urge to repel each other, leads to superconductivity.

Professor Lee said, “Our findings may be extended to future studies where magnetism and superconductivity are manipulated using spin-polarized and unpolarized currents, leading to novel antiferromagnetic memory devices and transistors controlling superconductivity.”

This study was published in Physical Review Letters (PRL) on November 27 as the Editor’s Suggestion. It was also featured in Viewpoint in Physics, in which the top 3% of PRL papers are presented with a commentary. It was also featured on Phys.org, which is a science news website led by the US national research institutes. Furthermore, the equipment designed and manufactured by Professor Lee’s team and used for the research was selected for the cover of Review of Scientific Instruments (RSI) in the October 2017 issue.

Professor Lee said, “When designing the experiment, we attempted to implement some decisive features. For instance, we included a spin control function using an antiferromagnetic probe, wide range variable temperature functions that were thought to be impossible in high-magnetic field structures, and multiple sample storage functions at low temperatures for systematic spin control experiments, rather than using simpler scanning probe microscopes with well-known principles or commercial microscopes. As a result, we were able to conduct systematic experiments on controlling magnetism and superconductivity, which competing groups would take years to replicate.”

He continued, “There were some minor difficulties in the basic science research environment such as the lack of a shared helium liquefier on campus and insufficient university-scale appreciation for large scale physics that inevitably takes time. We will do our best to lead the advancement of cutting-edge science through research projects expanding on this achievement in physical knowledge to practical devices and various technological innovations in measurements.” This research was funded by National Research Foundation of Korea.

Figure 1. Research concept illustration

The spin-polarized chromium (Cr) tip being scanned over the pristine superconducting area of the C2 magnetic order, represented in the background with electron pairs shown as coupled red spheres. The spin current through the tip induces the C4 magnetic order (yellow and blue plaquettes) with suppressed superconductivity in the sample because its spin fluctuations cannot mediate electron pairing, represented as decoupled red spheres in the plaquette area.

2018.01.05 View 6593

Controlling Superconductivity Using Spin Currents

(Professor Jhinhwan Lee and Dr. Seokhwan Choi)

A KAIST research team led by Professor Jhinhwan Lee of the Department of Physics has discovered a method to flip between superconducting and non-superconducting states within an iron-based superconductor using a type of electron microscopy. The team applied spin-polarized and non-polarized currents to locally change the magnetic order in the sample.

The team identified a basic physical principle required to develop transistors that control superconductivity and to implement novel magnetic memory at the atomic level. This study is the first report of a direct real-space observation of this type of control. In addition, this is the first direct atomic-scale demonstration of the correlation between magnetism and superconductivity.

The team controlled and observed the magnetic and electronic properties with a spin-polarized scanning tunneling microscope (SPSTM), a device that passes an atomically-sharp metal tip over the surface of a sample. The team introduced new ways to perform SPSTM using an antiferromagnetic chromium tip. An antiferromagnet is a material in which the magnetic fields of its atoms are ordered in an alternating up-down pattern such that it has a minimal stray magnetic field that can inadvertently kill the local superconductivity of the sample when used as an SPSTM tip.

To study the connection between the C4 magnetic order and the suppression of superconductivity, the team performed high-resolution SPSTM scans of the C4 state with chromium tips and compared them with simulations. The results led them to suggest that the low-energy spin fluctuations in the C4 state cannot mediate pairing between electrons in the typical FeAs band structure. This is critical because this paring of electrons, defying their natural urge to repel each other, leads to superconductivity.

Professor Lee said, “Our findings may be extended to future studies where magnetism and superconductivity are manipulated using spin-polarized and unpolarized currents, leading to novel antiferromagnetic memory devices and transistors controlling superconductivity.”

This study was published in Physical Review Letters (PRL) on November 27 as the Editor’s Suggestion. It was also featured in Viewpoint in Physics, in which the top 3% of PRL papers are presented with a commentary. It was also featured on Phys.org, which is a science news website led by the US national research institutes. Furthermore, the equipment designed and manufactured by Professor Lee’s team and used for the research was selected for the cover of Review of Scientific Instruments (RSI) in the October 2017 issue.

Professor Lee said, “When designing the experiment, we attempted to implement some decisive features. For instance, we included a spin control function using an antiferromagnetic probe, wide range variable temperature functions that were thought to be impossible in high-magnetic field structures, and multiple sample storage functions at low temperatures for systematic spin control experiments, rather than using simpler scanning probe microscopes with well-known principles or commercial microscopes. As a result, we were able to conduct systematic experiments on controlling magnetism and superconductivity, which competing groups would take years to replicate.”

He continued, “There were some minor difficulties in the basic science research environment such as the lack of a shared helium liquefier on campus and insufficient university-scale appreciation for large scale physics that inevitably takes time. We will do our best to lead the advancement of cutting-edge science through research projects expanding on this achievement in physical knowledge to practical devices and various technological innovations in measurements.” This research was funded by National Research Foundation of Korea.

Figure 1. Research concept illustration

The spin-polarized chromium (Cr) tip being scanned over the pristine superconducting area of the C2 magnetic order, represented in the background with electron pairs shown as coupled red spheres. The spin current through the tip induces the C4 magnetic order (yellow and blue plaquettes) with suppressed superconductivity in the sample because its spin fluctuations cannot mediate electron pairing, represented as decoupled red spheres in the plaquette area.

2018.01.05 View 6593 -

New Quantum Mechanical States Observed

(Professor Han (far right) and his research team)

A KAIST research team observed a new quantum mechanical magnetic state ‘Jeff = 3/2.’ This first observation of ‘Jeff=3/2’ could be the foundation for future research on superconductivity and quantum magnetism.

In quantum mechanics, total angular momentum is defined as the sum of spin and orbital angular momenta and is denoted with the ‘J.’ The newly identified magnetic moment can be described as a kind of angular momentum that occurs when specific conditions are met and has been denoted ‘Jeff’ with the meaning ‘effective angular momentum’ in the field. Jeff=3/2 has been a topic of discussion but was yet to be observed.

The research was co-led by Professor Myung Joon Han of the Department of Physics at Chung-Ang University in Korea, RIKEN in Japan, and the Argonne National Laboratory in the US. This research was published in Nature Communications on October 14, 2017.

In academia, spin-orbital coupling was known to lead to a unique quantum state and has been an active area of recent research. In contrast to magnetic moment by electron spin and orbital, the effective magnetic moment Jeff, formed from the coupling of the two, shows a unique ground state and interaction patterns, which could lead to new phenomena and properties.

Most studies in the last decade focused on ‘Jeff=1/2’, but there has not been any observation of ‘Jeff=3/2’, which led to slow progress. In 2014, the research team led by Prof. Han theoretically predicted the possibility of the ‘Jeff=3/2’ state in a certain type of materials based on molecular orbital, instead of atomic orbital. In the current study, the team applied the Selection Rule of quantum mechanics for the ‘Jeff=3/2’ state, which differs to the general spin moment, in order to experimentally detect this moment.

When electrons near the atomic nucleus are excited by X-rays, the excited electrons can be absorbed or re-emitted through interactions with other electrons. Here, the Selection Rule is applied to electrons. According to quantum mechanics, this rule is very unique in the ‘Jeff=3/2’ state and ‘Jeff=3/2’ is predicted to be distinguishable from general spin states. The prediction that was made using this idea was verified through the experiment using electrons extracted from tantalum at two different energy levels. In this material, the unique quantum mechanical interference by the ‘Jeff=3/2’ moment can be taken as direct evidence for its existence.

The new quantum state is very unique from any of the previously known magnetic states and this study could be the starting point for future research on the ‘Jeff=3/2’ moment. Further, this finding could contribute to future research on various properties of the magnetic states and its interactions.

(Figure 1: Crystal structure, MO levels, and RIXS process in GaTa4Se8.)

(Figure 2: Cluster model calculations of the L3 and L2 RIXS spectra)

2017.12.14 View 6431

New Quantum Mechanical States Observed

(Professor Han (far right) and his research team)

A KAIST research team observed a new quantum mechanical magnetic state ‘Jeff = 3/2.’ This first observation of ‘Jeff=3/2’ could be the foundation for future research on superconductivity and quantum magnetism.

In quantum mechanics, total angular momentum is defined as the sum of spin and orbital angular momenta and is denoted with the ‘J.’ The newly identified magnetic moment can be described as a kind of angular momentum that occurs when specific conditions are met and has been denoted ‘Jeff’ with the meaning ‘effective angular momentum’ in the field. Jeff=3/2 has been a topic of discussion but was yet to be observed.

The research was co-led by Professor Myung Joon Han of the Department of Physics at Chung-Ang University in Korea, RIKEN in Japan, and the Argonne National Laboratory in the US. This research was published in Nature Communications on October 14, 2017.

In academia, spin-orbital coupling was known to lead to a unique quantum state and has been an active area of recent research. In contrast to magnetic moment by electron spin and orbital, the effective magnetic moment Jeff, formed from the coupling of the two, shows a unique ground state and interaction patterns, which could lead to new phenomena and properties.

Most studies in the last decade focused on ‘Jeff=1/2’, but there has not been any observation of ‘Jeff=3/2’, which led to slow progress. In 2014, the research team led by Prof. Han theoretically predicted the possibility of the ‘Jeff=3/2’ state in a certain type of materials based on molecular orbital, instead of atomic orbital. In the current study, the team applied the Selection Rule of quantum mechanics for the ‘Jeff=3/2’ state, which differs to the general spin moment, in order to experimentally detect this moment.

When electrons near the atomic nucleus are excited by X-rays, the excited electrons can be absorbed or re-emitted through interactions with other electrons. Here, the Selection Rule is applied to electrons. According to quantum mechanics, this rule is very unique in the ‘Jeff=3/2’ state and ‘Jeff=3/2’ is predicted to be distinguishable from general spin states. The prediction that was made using this idea was verified through the experiment using electrons extracted from tantalum at two different energy levels. In this material, the unique quantum mechanical interference by the ‘Jeff=3/2’ moment can be taken as direct evidence for its existence.

The new quantum state is very unique from any of the previously known magnetic states and this study could be the starting point for future research on the ‘Jeff=3/2’ moment. Further, this finding could contribute to future research on various properties of the magnetic states and its interactions.

(Figure 1: Crystal structure, MO levels, and RIXS process in GaTa4Se8.)

(Figure 2: Cluster model calculations of the L3 and L2 RIXS spectra)

2017.12.14 View 6431 -

High-Speed Motion Core Technology for Magnetic Memory

(Professor Kab-Jin Kim of the Department of Physics)

A joint research team led by Professor Kab-Jin Kim of the Department of Physics, KAIST and Professor Kyung-Jin Lee at Korea University developed technology to dramatically enhance the speed of next generation domain wall-based magnetic memory. This research was published online in Nature Materials on September 25.

Currently-used memory materials, D-RAM and S-RAM, are fast but volatile, leading to memory loss when the power is switched off. Flash memory is non-volatile but slow, while hard disk drives (HDD) have greater storage but are high in energy usage and weak in physical shock tolerance.

To overcome the limitations of existing memory materials, ‘domain wall-based, magnetic memory’ is being researched. The core mechanism of domain wall magnetic memory is the movement of a domain wall by the current. Non-volatility is secured by using magnetic nanowires and the lack of mechanical rotation reduced power usage. This is a new form of high density, low power next-generation memory.

However, previous studies showed the speed limit of domain wall memory to be hundreds m/s at maximum due to the ‘Walker breakdown phenomenon’, which refers to velocity breakdown from the angular precession of a domain wall. Therefore, there was a need to develop core technology to remove the Walker breakdown phenomenon and increase the speed for the commercialization of domain wall memory.

Most domain wall memory studies used ferromagnetic bodies, which cannot overcome the Walker breakdown phenomenon. The team discovered that the use of ‘ferrimagnetic‘ GdFeCo at certain conditions could overcome the Walker breakdown phenomenon and using this mechanism they could increase domain wall speed to over 2Km/s at room temperature.

Domain wall memory is high-density, low-power, and non-volatile memory. The memory could be the leading next-generation memory with the addition of the high speed property discovered in this research.

Professor Kim said, “This research is significant in discovering a new physical phenomenon at the point at which the angular momentum of a ferrimagnetic body is 0 and it is expected to advance the implementation of next-generation memory in the future.”

This research was funded by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea Government (MSIP) (No. 2017R1C1B2009686, NRF-2016R1A5A1008184) and by the DGIST R&D Program of the Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning (17-BT-02).

(Figure 1. Concept Map of Domain Wall Memory Material using Ferrimagnetic Body)

(Figure 2. Scheme and Experimental Results of Domain Wall Speed Measurements)

2017.10.30 View 9795

High-Speed Motion Core Technology for Magnetic Memory

(Professor Kab-Jin Kim of the Department of Physics)

A joint research team led by Professor Kab-Jin Kim of the Department of Physics, KAIST and Professor Kyung-Jin Lee at Korea University developed technology to dramatically enhance the speed of next generation domain wall-based magnetic memory. This research was published online in Nature Materials on September 25.

Currently-used memory materials, D-RAM and S-RAM, are fast but volatile, leading to memory loss when the power is switched off. Flash memory is non-volatile but slow, while hard disk drives (HDD) have greater storage but are high in energy usage and weak in physical shock tolerance.

To overcome the limitations of existing memory materials, ‘domain wall-based, magnetic memory’ is being researched. The core mechanism of domain wall magnetic memory is the movement of a domain wall by the current. Non-volatility is secured by using magnetic nanowires and the lack of mechanical rotation reduced power usage. This is a new form of high density, low power next-generation memory.

However, previous studies showed the speed limit of domain wall memory to be hundreds m/s at maximum due to the ‘Walker breakdown phenomenon’, which refers to velocity breakdown from the angular precession of a domain wall. Therefore, there was a need to develop core technology to remove the Walker breakdown phenomenon and increase the speed for the commercialization of domain wall memory.

Most domain wall memory studies used ferromagnetic bodies, which cannot overcome the Walker breakdown phenomenon. The team discovered that the use of ‘ferrimagnetic‘ GdFeCo at certain conditions could overcome the Walker breakdown phenomenon and using this mechanism they could increase domain wall speed to over 2Km/s at room temperature.

Domain wall memory is high-density, low-power, and non-volatile memory. The memory could be the leading next-generation memory with the addition of the high speed property discovered in this research.

Professor Kim said, “This research is significant in discovering a new physical phenomenon at the point at which the angular momentum of a ferrimagnetic body is 0 and it is expected to advance the implementation of next-generation memory in the future.”

This research was funded by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea Government (MSIP) (No. 2017R1C1B2009686, NRF-2016R1A5A1008184) and by the DGIST R&D Program of the Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning (17-BT-02).

(Figure 1. Concept Map of Domain Wall Memory Material using Ferrimagnetic Body)

(Figure 2. Scheme and Experimental Results of Domain Wall Speed Measurements)

2017.10.30 View 9795 -

Controlling 3D Behavior of Biological Cells Using Laser Holographic Techniques

A research team led by Professor YongKeun Park of the Physics Department at KAIST has developed an optical manipulation technique that can freely control the position, orientation, and shape of microscopic samples having complex shapes. The study has been published online in Nature Communications on May 22.

Conventional optical manipulation techniques called “optical tweezers,” have been used as an invaluable tool for exerting micro-scale force on microscopic particles and manipulating three-dimensional (3-D) positions of particles. Optical tweezers employ a tightly-focused laser whose beam diameter is smaller than one micrometer (1/100 of hair thickness), which can generate attractive force on neighboring microscopic particles moving toward the beam focus. Controlling the positions of the beam focus enabled researchers to hold the particles and move them freely to other locations so they coined the name “optical tweezers,” and have been widely used in various fields of physical and biological studies.

So far, most experiments using optical tweezers have been conducted for trapping spherical particles because physical principles can easily predict optical forces and the responding motion of microspheres. For trapping objects having complicated shapes, however, conventional optical tweezers induce unstable motion of such particles, and controllable orientation of such objects is limited, which hinder controlling the 3-D motion of microscopic objects having complex shapes such as living cells.

The research team has developed a new optical manipulation technique that can trap complex objects of arbitrary shapes. This technique first measures 3-D structures of an object in real time using a 3-D holographic microscope, which shares the same physical principle of X-Ray CT imaging. Based on the measured 3-D shape of the object, the researchers precisely calculates the shape of light that can stably control the object. When the shape of light is the same as the shape of the object, the energy of the object is minimized, which provides the stable trapping of the object having the complicated shape.

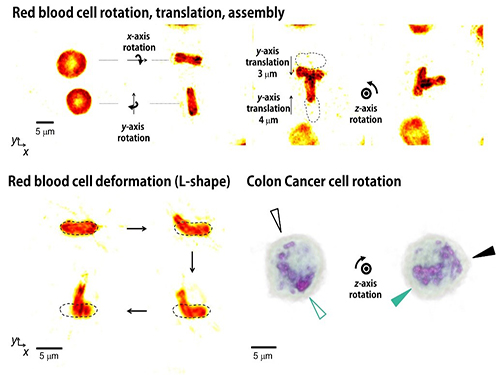

Moreover, by controlling the shape of light to have various positions, directions, and shapes of objects, it is possible to freely control the 3-D motion of the object and make the object have a desired shape. This process resembles the generation of a mold for casting a statue having desired shape so the researchers coined the name of the present technique “tomographic mold for optical trapping (TOMOTRAP).” The team succeeded in trapping individual human red blood cells stably, rotating them with desired orientations, folding them in an L-shape, and assembling two red blood cells together to form a new structure. In addition, colon cancer cells having a complex structure could be stably trapped and rotated at desired orientations. All of which have been difficult to be realized by the conventional optical techniques.

Professor Park said, “Our technique has the advantage of controlling the 3-D motion of complex shaped objects without knowing prior information about their shape and optical characteristics, and can be applied in various fields including physics, optics, nanotechnology, and medical science.”

Dr. Kyoohyun Kim, the lead author of this paper, noted that this technique can induce controlled deformation of biological cells with desired shapes. “This approach can be also applied to real-time monitoring of surgical prognosis of cellular-level surgeries for capturing and deforming cells as well as subcellular organelles,” added Kim.

Figure 1. Concept of optical manipulation techniques

Figure 2. Experimental setup

Figure 3. Research results

2017.05.25 View 9806

Controlling 3D Behavior of Biological Cells Using Laser Holographic Techniques

A research team led by Professor YongKeun Park of the Physics Department at KAIST has developed an optical manipulation technique that can freely control the position, orientation, and shape of microscopic samples having complex shapes. The study has been published online in Nature Communications on May 22.

Conventional optical manipulation techniques called “optical tweezers,” have been used as an invaluable tool for exerting micro-scale force on microscopic particles and manipulating three-dimensional (3-D) positions of particles. Optical tweezers employ a tightly-focused laser whose beam diameter is smaller than one micrometer (1/100 of hair thickness), which can generate attractive force on neighboring microscopic particles moving toward the beam focus. Controlling the positions of the beam focus enabled researchers to hold the particles and move them freely to other locations so they coined the name “optical tweezers,” and have been widely used in various fields of physical and biological studies.

So far, most experiments using optical tweezers have been conducted for trapping spherical particles because physical principles can easily predict optical forces and the responding motion of microspheres. For trapping objects having complicated shapes, however, conventional optical tweezers induce unstable motion of such particles, and controllable orientation of such objects is limited, which hinder controlling the 3-D motion of microscopic objects having complex shapes such as living cells.

The research team has developed a new optical manipulation technique that can trap complex objects of arbitrary shapes. This technique first measures 3-D structures of an object in real time using a 3-D holographic microscope, which shares the same physical principle of X-Ray CT imaging. Based on the measured 3-D shape of the object, the researchers precisely calculates the shape of light that can stably control the object. When the shape of light is the same as the shape of the object, the energy of the object is minimized, which provides the stable trapping of the object having the complicated shape.

Moreover, by controlling the shape of light to have various positions, directions, and shapes of objects, it is possible to freely control the 3-D motion of the object and make the object have a desired shape. This process resembles the generation of a mold for casting a statue having desired shape so the researchers coined the name of the present technique “tomographic mold for optical trapping (TOMOTRAP).” The team succeeded in trapping individual human red blood cells stably, rotating them with desired orientations, folding them in an L-shape, and assembling two red blood cells together to form a new structure. In addition, colon cancer cells having a complex structure could be stably trapped and rotated at desired orientations. All of which have been difficult to be realized by the conventional optical techniques.

Professor Park said, “Our technique has the advantage of controlling the 3-D motion of complex shaped objects without knowing prior information about their shape and optical characteristics, and can be applied in various fields including physics, optics, nanotechnology, and medical science.”

Dr. Kyoohyun Kim, the lead author of this paper, noted that this technique can induce controlled deformation of biological cells with desired shapes. “This approach can be also applied to real-time monitoring of surgical prognosis of cellular-level surgeries for capturing and deforming cells as well as subcellular organelles,” added Kim.

Figure 1. Concept of optical manipulation techniques

Figure 2. Experimental setup

Figure 3. Research results

2017.05.25 View 9806 -

Dr.Sung-Chul Shin Inaugurated as the 16th President of KAIST

(President Shin delivers his inaugural address at the inauguration ceremony on March 15.)

Professor Sung-Chul Shin was officially inaugurated as its 16th president of KAIST on March 15 in a ceremony at the KAIST Auditorium.

The celebration began with a procession by dignitaries including the KAIST Board of Trustees Chairman Jang-Moo Lee, the National Academy of Sciences of Korea President Sook-Il Kwun, Daejeon City Mayor Sun-Taik Kwon, National Assemblyman Sangmin Lee, KAIST Alumni Association President Jungsik Koh. Academic leaders, foreign envoys, faculty, students, and staff members of KAIST joined the ceremony.

In his inaugural speech, President Shin presented a new vision for KAIST to become a global value creator in the Fourth Industrial Revolution. He said that KAIST has played a pivotal role in the nation’s industrialization and information revolution over the past half century and, with the advent of the new industry paradigm, KAIST should be now responsible for being a new value creator, not only serving the nation but pursuing global betterment. “KAIST should be a global hub of new knowledge and technology creation,” he emphasized.

Envisioning a “Global Value-Creative World-Leading University,” President Shin aims for KAIST to be an institution which can create global value as an innovative global leading research university. To realize this vision, he pledged to continue innovation in five areas of education, research & development, technology commercialization, globalization of the campus, and future strategy for the university and the nation.

In the educational innovation, he emphasized multidisciplinary studies, team work, and leadership training for students. To this end, KAIST will expand the non-departmental courses toward entire 4-year course while concurrently operating the existing system of declaring a major in students’ second year. KAIST will offer mandatory courses in humanities, social sciences, and arts and most classes will be run by team-based learning and group research activities. “KAIST Global Leadership Center” will support students to develop the qualities required for collaboration and the global leaderships.

With respect to the research innovation, President Shin said KAIST will establish “Convergence Research Matrix” system to foster strategic research groups for interdisciplinary and convergence collaboration across a wide range of divisions and departments. “Based on the CRMS, we will identify 10 flagship future-oriented convergence research areas for KAIST to truly claim its reputation as a world-leading research university,” he said. He added he will also introduce the “Collaborative Research Lab” system to better retain the academic successes without interruption, and to improve the continuity of research. “We will strive to organize teams of professors in diverse age groups to work together in mutually complementary fields,” he added.

In terms of technological commercialization, he hopes that KAIST to be a role model. He said he will make every effort to establish a resilient R&DB environment with ideas, technologies, and entrepreneurship. KAIST will rev up a new university-industry cooperation, fully sponsoring the creation of “Technology in-Kind Investment Companies.”

KAIST will continue to take initiative for globalization. He said KAIST will create an ‘English-Only Zone’ at the campus, saying that his ultimate goal is to create Korean-English bilingual campus. He also asked the foreign community to make their effort to learn Korean and Korean culture while staying at KAIST, in an effort to embrace diversity at the campus. He plans to increase the ratio of foreign faculty from nine percent to 15 percent, while doubling the current foreign student enrollment ratio of five percent.

As for the future strategy for the university and the nation, he will soon finalize the long-term strategic plan of “Vision 2031” that will lay out a roadmap for KAIST future direction toward its 60th anniversary. KAIST will also play a fundamental role in shaping national policies and strategies for science and technology by operating think-tank groups that consist of KAIST beyond disciplines. These think-tanks will design detailed development plans for KAIST as well as for national strategies for the advancement of science and technology.

He said that such institutional innovation will not be completed without the support, dedication, and passion of all KAIST members, adding that he will strive to serve them with 3Cs (Change, Communication, and Care).

For the full text of President Shin’s inaugural address, please click.

2017.03.15 View 13188

Dr.Sung-Chul Shin Inaugurated as the 16th President of KAIST

(President Shin delivers his inaugural address at the inauguration ceremony on March 15.)

Professor Sung-Chul Shin was officially inaugurated as its 16th president of KAIST on March 15 in a ceremony at the KAIST Auditorium.

The celebration began with a procession by dignitaries including the KAIST Board of Trustees Chairman Jang-Moo Lee, the National Academy of Sciences of Korea President Sook-Il Kwun, Daejeon City Mayor Sun-Taik Kwon, National Assemblyman Sangmin Lee, KAIST Alumni Association President Jungsik Koh. Academic leaders, foreign envoys, faculty, students, and staff members of KAIST joined the ceremony.

In his inaugural speech, President Shin presented a new vision for KAIST to become a global value creator in the Fourth Industrial Revolution. He said that KAIST has played a pivotal role in the nation’s industrialization and information revolution over the past half century and, with the advent of the new industry paradigm, KAIST should be now responsible for being a new value creator, not only serving the nation but pursuing global betterment. “KAIST should be a global hub of new knowledge and technology creation,” he emphasized.

Envisioning a “Global Value-Creative World-Leading University,” President Shin aims for KAIST to be an institution which can create global value as an innovative global leading research university. To realize this vision, he pledged to continue innovation in five areas of education, research & development, technology commercialization, globalization of the campus, and future strategy for the university and the nation.

In the educational innovation, he emphasized multidisciplinary studies, team work, and leadership training for students. To this end, KAIST will expand the non-departmental courses toward entire 4-year course while concurrently operating the existing system of declaring a major in students’ second year. KAIST will offer mandatory courses in humanities, social sciences, and arts and most classes will be run by team-based learning and group research activities. “KAIST Global Leadership Center” will support students to develop the qualities required for collaboration and the global leaderships.

With respect to the research innovation, President Shin said KAIST will establish “Convergence Research Matrix” system to foster strategic research groups for interdisciplinary and convergence collaboration across a wide range of divisions and departments. “Based on the CRMS, we will identify 10 flagship future-oriented convergence research areas for KAIST to truly claim its reputation as a world-leading research university,” he said. He added he will also introduce the “Collaborative Research Lab” system to better retain the academic successes without interruption, and to improve the continuity of research. “We will strive to organize teams of professors in diverse age groups to work together in mutually complementary fields,” he added.

In terms of technological commercialization, he hopes that KAIST to be a role model. He said he will make every effort to establish a resilient R&DB environment with ideas, technologies, and entrepreneurship. KAIST will rev up a new university-industry cooperation, fully sponsoring the creation of “Technology in-Kind Investment Companies.”

KAIST will continue to take initiative for globalization. He said KAIST will create an ‘English-Only Zone’ at the campus, saying that his ultimate goal is to create Korean-English bilingual campus. He also asked the foreign community to make their effort to learn Korean and Korean culture while staying at KAIST, in an effort to embrace diversity at the campus. He plans to increase the ratio of foreign faculty from nine percent to 15 percent, while doubling the current foreign student enrollment ratio of five percent.

As for the future strategy for the university and the nation, he will soon finalize the long-term strategic plan of “Vision 2031” that will lay out a roadmap for KAIST future direction toward its 60th anniversary. KAIST will also play a fundamental role in shaping national policies and strategies for science and technology by operating think-tank groups that consist of KAIST beyond disciplines. These think-tanks will design detailed development plans for KAIST as well as for national strategies for the advancement of science and technology.

He said that such institutional innovation will not be completed without the support, dedication, and passion of all KAIST members, adding that he will strive to serve them with 3Cs (Change, Communication, and Care).

For the full text of President Shin’s inaugural address, please click.

2017.03.15 View 13188 -

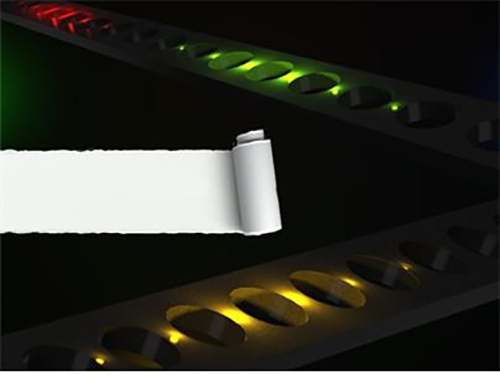

Semiconductor Photonic Nanocavities on Paper Substrates

Professor Yong-Hoon Cho of the Department of Physics and his team at KAIST have developed a semiconductor photonic nanocavity laser that can operate on a paper substrate.

The researchers hope that this novel method, which involves transferring nano-sized photonic crystal particles onto a paper substrate with high absorptiveness, will enable the diagnoses of various diseases by using high-tech semiconductor sensors at low cost.

The results of this research were published in the November 17th, 2016, issue of Advanced Materials.

Photonic crystals, which utilize light as a medium to provide high bandwidths, can transfer large amounts of information. Compared with their electronic counterparts, photonic crystals also consume less energy to operate.

Normally, semiconductor photonic particles require substrates, which play only a passive role in the assembly and endurance of individual, functional photonic components. These substrates, however, are bulky and environmentally hazardous as they are made up of non-biodegradable materials.

The research team overcame these two shortcomings by replacing a semiconductor substrate with standard paper. The substrate’s mass was reduced considerably, and because paper is made from trees, it degrades. Paper can be easily and cheaply acquired from our surroundings, which drastically reduces the unit cost of semiconductors.

In addition, paper possesses superior mechanical characteristics. It is flexible and can be repeatedly folded and unfolded without being torn. These are traits that have long been sought by researchers for existing flexible substrates.

The research team used a micro-sized stamp to detach photonic crystal nanobeam cavities selectively from their original substrate and transfer them onto a new paper substrate. Using this technique, the team removed nanophotonic crystals that had been patterned (using a process of selectively etching circuits onto a substrate) onto a semiconductor substrate with a high degree of integration, and realigned them as desired on a paper substrate.

The nanophotonic crystals that the team combined with paper in this research were 0.5 micrometers in width, 6 micrometers in length, and 0.3 micrometers in height—about one-hundredth of the width of a single hair (0.1 millimeter).

The team also transferred their photonic crystals onto paper with a fluid channel, which proved that it could be used as a refractive index sensor. As can be seen in current commercial pregnancy diagnosis kits, paper has high absorptiveness. Since photonic crystal particles have high sensitivity, they are highly suitable for applications such as sensors.

Professor Cho stated that “by using paper substrates, this technology can greatly contribute to the rising field of producing environmentally-friendly photonic particles” and “by combining inexpensive paper and high-performance photonic crystal sensors, we can obtain low prices as well as designing appropriate technologies with high performance.”

Dr. Sejeong Kim of the Department of Physics participated in this study as the first author, and Professor Kwanwoo Shin of Sogang University and Professor Yong-Hee Lee of KAIST also took part in this research. The research was supported by the National Research Foundation’s Mid-Career Researcher Program, and the Climate Change Research Hub of KAIST.

Figure 1. Illustration of photonic crystal lasers on paper substrates

Figure 2. Photonic crystal resonator laser and refractive index sensor operating on paper substrates

2017.03.01 View 8327

Semiconductor Photonic Nanocavities on Paper Substrates

Professor Yong-Hoon Cho of the Department of Physics and his team at KAIST have developed a semiconductor photonic nanocavity laser that can operate on a paper substrate.

The researchers hope that this novel method, which involves transferring nano-sized photonic crystal particles onto a paper substrate with high absorptiveness, will enable the diagnoses of various diseases by using high-tech semiconductor sensors at low cost.

The results of this research were published in the November 17th, 2016, issue of Advanced Materials.

Photonic crystals, which utilize light as a medium to provide high bandwidths, can transfer large amounts of information. Compared with their electronic counterparts, photonic crystals also consume less energy to operate.

Normally, semiconductor photonic particles require substrates, which play only a passive role in the assembly and endurance of individual, functional photonic components. These substrates, however, are bulky and environmentally hazardous as they are made up of non-biodegradable materials.

The research team overcame these two shortcomings by replacing a semiconductor substrate with standard paper. The substrate’s mass was reduced considerably, and because paper is made from trees, it degrades. Paper can be easily and cheaply acquired from our surroundings, which drastically reduces the unit cost of semiconductors.

In addition, paper possesses superior mechanical characteristics. It is flexible and can be repeatedly folded and unfolded without being torn. These are traits that have long been sought by researchers for existing flexible substrates.

The research team used a micro-sized stamp to detach photonic crystal nanobeam cavities selectively from their original substrate and transfer them onto a new paper substrate. Using this technique, the team removed nanophotonic crystals that had been patterned (using a process of selectively etching circuits onto a substrate) onto a semiconductor substrate with a high degree of integration, and realigned them as desired on a paper substrate.

The nanophotonic crystals that the team combined with paper in this research were 0.5 micrometers in width, 6 micrometers in length, and 0.3 micrometers in height—about one-hundredth of the width of a single hair (0.1 millimeter).

The team also transferred their photonic crystals onto paper with a fluid channel, which proved that it could be used as a refractive index sensor. As can be seen in current commercial pregnancy diagnosis kits, paper has high absorptiveness. Since photonic crystal particles have high sensitivity, they are highly suitable for applications such as sensors.

Professor Cho stated that “by using paper substrates, this technology can greatly contribute to the rising field of producing environmentally-friendly photonic particles” and “by combining inexpensive paper and high-performance photonic crystal sensors, we can obtain low prices as well as designing appropriate technologies with high performance.”

Dr. Sejeong Kim of the Department of Physics participated in this study as the first author, and Professor Kwanwoo Shin of Sogang University and Professor Yong-Hee Lee of KAIST also took part in this research. The research was supported by the National Research Foundation’s Mid-Career Researcher Program, and the Climate Change Research Hub of KAIST.

Figure 1. Illustration of photonic crystal lasers on paper substrates

Figure 2. Photonic crystal resonator laser and refractive index sensor operating on paper substrates

2017.03.01 View 8327