people

International Herald Tribune carried a feature story on KAIST"s ongoing reform efforts on the front page of its Jan. 19-20 edition. The following is the full text of the report.

http://www.iht.com/articles/2008/01/18/asia/school.php

By Choe Sang-Hun

Friday, January 18, 2008

DAEJEON, South Korea: In Professor Cho Dong Ho"s laboratory at Kaist, South Korea"s top science and technology university, researchers are trying to develop technology that could let you fold a notebook-size electronic display and carry it in your pocket like a handkerchief.

It"s too early to say when something like this might be commercially available. But the experiment has already achieved one important breakthrough: it has mobilized professors from eight departments to collaborate on an idea proposed by a student.

This arrangement is almost unheard of in South Korea, where the norm is for a senior professor to dictate research projects to his own cloistered team. But it"s only one change afoot at this government-financed university, which has ambitions to transform the culture of South Korean science, and more.

"When we first got the student"s idea on what a future display should look like, we thought it was crazy, stuff from science fiction," said Cho, director of Kaist"s Institute for Information Technology Convergence. "But under our new president, we are being urged to try things no one else is likely to."

That university president is Suh Nam Pyo, 71, a mechanical engineer who used to be an administrator at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and who is spearheading closely watched changes that are expected to have ramifications far beyond this campus 90 minutes by car south of Seoul.

His moves so far, from requiring professors to teach in English to basing student admissions on factors other than test scores, are aimed at making the university, and by extension South Korean society, much more competitive on a world scale.

When the South Korean government hired Suh in 2006 to shake up the state-financed Korean Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (which formally changed its name to its acronym, Kaist, on Jan. 1) the country"s leading schools faced a crisis. The old system, which guaranteed free tuition to lure promising students into science and technology, the drivers of South Korea"s industrial growth, was no longer working as well as it used to.

Prosperity was allowing those young people to choose fields of study once viewed as luxuries, like literature and history. Worse, increasing numbers were choosing to study abroad, mostly in the United States, and then not returning home. The fear was that South Korean institutions and enterprises would be gutted of expertise.

That concern was voiced at a news conference Monday by the president-elect, Lee Myung Bak, who said the educational system "isn"t producing talent that can compete globally."

Kaist, which was established in 1971 with foreign aid, has a special place in South Korean education. The military strongman Park Chung Hee recruited the brightest young people to train there as scientists and engineers. Villagers put up a large banner to celebrate whenever a local child was admitted.

"When I was a student here in the mid-1980s, some students stopped before the national flag at the library in the morning and observed a moment of silence, vowing to dedicate ourselves to the nation"s industrial development," said Cho Byung Jin, a professor of electrical engineering.

Since his arrival, Suh has become the most talked-about campus reformer in South Korea by taking on some of Kaist"s most hallowed traditions.

In a first for a Korean university, Suh has insisted that all classes eventually be taught in English, starting with those aimed at freshmen.

"I want Kaist students to work all over the world," Suh said last week. "I don"t want them to be like other Koreans who attend international conferences and have a lunch among themselves because they are afraid of speaking in English."

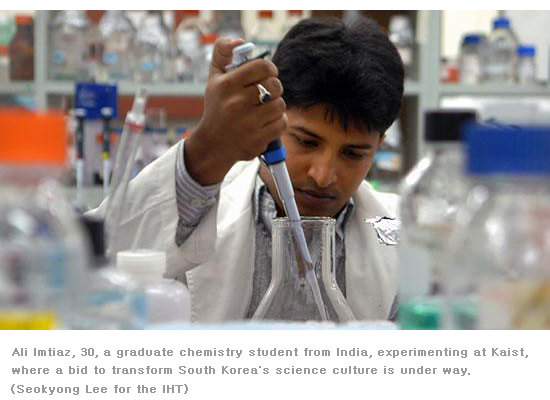

The move to English supports another of his changes: opening undergraduate degree programs to talented non-Koreans. Last year Kaist filled 51 of its 700 admission slots with foreign students on full scholarships. Meanwhile, he has ended free tuition for all; any student whose grade average falls below a B must pay up to $16,000 a year.

"My dream is to make Kaist a globalized university, one of the best universities in the world," he said.

In what may have been his most daring move, the university denied tenure to 15 of the 35 professors who applied last September. Until then, few if any applicants had failed tenure review in the university"s 36-year history.

In this education-obsessed country, Suh"s actions have been watched intensely for their broader impact. More than 82 percent of all high school graduates go on to higher education. What university a South Korean attends in his 20s can determine his position and salary in his 50s, a factor behind recent expos?of prominent South Koreans who faked prestigious diplomas.

The system is widely deplored but seldom challenged. From kindergarten, a child"s life is shaped largely by a single goal: doing well in examinations, particularly the all-important national college entrance exam. High school students plod through rote learning from dawn to dusk. Tutoring by "exam doctors" is a multibillion-dollar industry. During vacations, students attend private cram schools, which numbered 33,000 in 2006.

One result is a disciplined and conformist work force, an advantage when South Korea rapidly industrialized by copying technology from others. But now, with the country trying to climb the innovation ladder, the rigid school system is proving a stumbling block.

The nation"s highly hierarchical ways are often cited to explain how Hwang Woo Suk, the disgraced South Korean scientist who claimed he had produced stems cells from a cloned human embryo, could fabricate research findings with the complicity of junior associates.

The ambitious head overseas. Last year, 62,392 South Korean students were enrolled in U.S. colleges and universities, making them the third-largest foreign student group, after Indians (83,833) and Chinese (67,723), according to the U.S. Institute of International Education.

Some start earlier. About 35,000 South Korean children below college age go abroad each year, most to the United States to learn English.

Against this backdrop, Kaist has been experimenting with test-free admissions. For this year"s class, it brought applicants in for interviews and debates and make presentations while professors looked for creativity and leadership.

"About 20 percent of the students who formerly would have won admission didn"t make it under our new guidelines," Suh said. "We are looking for rough diamonds."

Challenging the status quo can be risky.

The Science and Technology Ministry, which oversees Kaist, had first looked outside South Korea for someone to lead the changes, choosing the Nobel physics laureate Robert Laughlin, who became the first foreigner to head a South Korean university in 2004. But he returned to Stanford University within two years, after the faculty rebelled against him for attempting some of the same changes Suh has instituted, accusing him, among other things, of insensitivity to Korean ways.

Suh"s Korean roots and experience shield him from such charges. He did not emigrate to the United States until he was 18 and has worked at Korean universities as well as serving as assistant director at the U.S. National Science Foundation in the 1980s and head of MIT"s department of mechanical engineering from 1991 to 2001.

"Reform entails sacrifices, but even if we don"t reform, there will be sacrifices," Suh said. "The difference is that if we don"t reform and don"t encourage competition, it"s the best people who are sacrificed."

So far, Suh"s innovations have mostly received favorable reviews.

Education Minister Kim Shi Il called them a "very desirable way of making Korea"s universities more competitive globally." The newspaper JoongAng Daily (which publishes an English-language version in partnership with the IHT) praised him for "smashing the iron rice bowls" (ending guaranteed job security) for professors and said, "We must learn from Kaist."

Ewan Stewart, a British physicist who has taught at Kaist since 1999, said, "Many of the things President Suh is saying were things I felt should have been said a long time ago."

Chung Joo Yeon, a first-year student, said she accepted the need for classes in English, but complained that some professors had no experience teaching in the language.

But Cho, the electrical engineering professor, said: "It"s no longer a matter of choice. If we want to maintain our school"s standards, we must draw talents from countries around the world, and that means we must conduct our classes in English."

Meanwhile, Lee has promised that as president he will give universities more autonomy by taking the "government"s hands off" how they select their students.

-

research KAIST Professor Jee-Hwan Ryu Receives Global IEEE Robotics Journal Best Paper Award

- Professor Jee-Hwan Ryu of Civil and Environmental Engineering receives the Best Paper Award from the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) Robotics Journal, officially presented at ICRA, a world-renowned robotics conference. - This is the highest level of international recognition, awarded to only the top 5 papers out of approximately 1,500 published in 2024. - Securing a new working channel technology for soft growing robots expands the practicality and application possib

2025-06-09 -

event KAIST School of Computing Unveils 'KRAFTON Building,' A Symbol of Collective Generosity

< (From the fifth from the left) Provost and Executive Vice President Gyun Min Lee, Auditor Eun Woo Lee, President Kwang-Hyung Lee, Dean of the School of Computing Seok-Young Ryu, former Krafton member and donor Woong-Hee Cho, Krafton Chairman Byung-Gyu Chang > KAIST announced on May 20th the completion of the expansion building for its School of Computing, the "KRAFTON Building." The project began in June 2021 with an ₩11 billion donation from KRAFTON and its employees, eventually gr

2025-05-21 -

event Life Springs at KAIST: A Tale of Two Special Campus Families

A Gift of Life on Teachers' Day: Baby Geese Born at KAIST Pond On Teachers' Day, a meaningful miracle of life arrived at the KAIST campus. A pair of geese gave birth to two goslings by the duck pond. < On Teachers' Day, a pair of geese and their goslings leisurely swim in the pond. > The baby goslings, covered in yellow down, began exploring the pond's edge, scurrying about, while their aunt geese steadfastly stood by. Their curious glances, watchful gazes, playful hops on water

2025-05-21 -

event KAIST Art Museum Showcases the Works of Van Gogh, Cy Twombly, and More at "The Vault of Masterpieces"

KAIST (President Kwang Hyung Lee) opened a special exhibition, "The Vault of Masterpieces", featuring the architects of the Gallerist Hong Gyu Shin, who is active in New York, on April 29th. Since its opening in December 2024, the KAIST Museum of Art, which has mainly exhibited works from its own collection, has boldly invited internationally renowned Gallerist Shin Hong-gyu to hold its first full-scale special exhibition, displaying a large number of his collections in the center of the camp

2025-04-30 -

event Formosa Group of Taiwan to Establish Bio R&D Center at KAIST Investing 12.5 M USD

KAIST (President Kwang-Hyung Lee) announced on February 17th that it signed an agreement for cooperation in the bio-medical field with Formosa Group, one of the three largest companies in Taiwan. < Formosa Group Chairman Sandy Wang and KAIST President Kwang-Hyung Lee at the signing ceremony > Formosa Group Executive Committee member and Chairman Sandy Wang, who leads the group's bio and eco-friendly energy sectors, decided to establish a bio-medical research center within KAIST and i

2025-02-17