research

- Multiple forms of a non-functional, unfolded protein follow different pathways and timelines to reach its folded, functional state, a study reveals. -

< Professor Hyotcherl Ihee (left), Professor Young Min Rhee (center), and Dr. Tae Wu Kim (right) >

KAIST researchers have used an X-ray method to track how proteins fold, which could improve computer simulations of this process, with implications for understanding diseases and improving drug discovery. Their findings were reported in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS) on June 30.

When proteins are translated from their DNA codes, they quickly transform from a non-functional, unfolded state into their folded, functional state. Problems in folding can lead to diseases like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s.

“Protein folding is one of the most important biological processes, as it forms the functioning 3D protein structure,” explained the physical chemist Hyotcherl Ihee of the Department of Chemistry at KAIST. Dr. Tae Wu Kim, the lead author of this research from Ihee’s group, added, “Understanding the mechanisms of protein folding is important, and could pave the way for disease study and drug development.”

Ihee’s team developed an approach using an X-ray scattering technique to uncover how the protein cytochrome c folds from its initial unfolded state. This protein is composed of a chain of 104 amino acids with an iron-containing heme molecule. It is often used for protein folding studies.

The researchers placed the protein in a solution and shined ultraviolet light on it. This process provides electrons to cytochrome c, reducing the iron within it from the ferric to the ferrous form, which initiates folding. As this was happening, the researchers beamed X-rays at very short intervals onto the sample. The X-rays scattered off all the atomic pairs in the sample and a detector continuously recorded the X-ray scattering patterns. The X-ray scattering patterns provided direct information regarding the 3D protein structure and the changes made in these patterns over time showed real-time motion of the protein during the folding process.

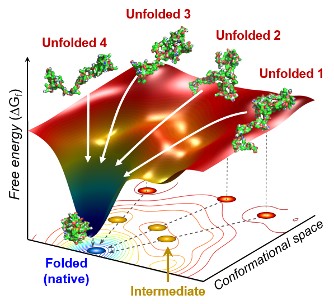

The team found cytochrome c proteins initially exist in a wide variety of unfolded states. Once the folding process is triggered, they stop by a group of intermediates within 31.6 microseconds, and then those intermediates follow different pathways with different folding times to reach an energetically stable folded state.

“We don’t know if this diversity in folding paths can be generalized to other proteins,” Ihee confessed. He continued, “However, we believe that our approach can be used to study other protein folding systems.”

Ihee hopes this approach can improve the accuracy of models that simulate protein interactions by including information on their unstructured states. These simulations are important as they can help identify barriers to proper folding and predict a protein’s folded state given its amino acid sequence. Ultimately, the models could help clarify how some diseases develop and how drugs interact with various protein structures.

Ihee’s group collaborated with Professor Young Min Rhee at the KAIST Department of Chemistry, and this work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) and the Institute for Basic Science (IBS).

Figure. The scientists found that non-functional unfolded forms of the protein cytochrome c follow different pathways and timelines to reach a stable functional folded state.

Publications:

Kim, T. W., et al. (2020) ‘Protein folding from heterogeneous unfolded state revealed by time-resolved X-ray solution scattering’. PNAS. Volume 117. Issue 26. Page 14996-15005. Available online at https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1913442117

Profile: Hyotcherl Ihee, Ph.D.

Professor

hyotcherl.ihee@kaist.ac.kr

http://time.kaist.ac.kr/

Ihee Laboratory

Department of Chemistry

KAIST

https://www.kaist.ac.kr

Daejeon 34141, Korea

Profile: Young Min Rhee, Ph.D.

Professor

ymrhee@kaist.ac.kr

http://singlet.kaist.ac.kr

Rhee Research Group

Department of Chemistry

KAIST

https://www.kaist.ac.kr

Daejeon 34141, Korea

(END)

-

research A KAIST Research Team Observes the Processes of Memory and Cognition in Real Time

The human brain contains approximately 86 billion neurons and 600 trillion synapses that exchange signals between the neurons to help us control the various functions of the brain including cognition, emotion, and memory. Interestingly, the number of synapses decrease with age or as a result of diseases like Alzheimer’s, and research on synapses thus attracts a lot of attention. However, limitations have existed in observing the dynamics of synapse structures in real time. On January 9,

2024-01-18 -

research KAIST research team develops clathrin assembly for targeted protein delivery to cancer cells

In order to effectively treat cancer without additional side effects, we need a way to deliver drugs specifically to tumor cells. Protein assemblies have been widely used for drug delivery in the field of cancer treatment, but to use them for drug delivery they must first be functionalized, meaning they must be bound to the protein that recognizes the target tumor cell and deliver a drug that kills it. However, the functionalization process of protein assemblies is very complex, inefficient, and

2023-03-22 -

research A Genetic Change for Achieving a Long and Healthy Life

Researchers identified a single amino acid change in the tumor suppressor protein in PTEN that extends healthy periods while maintaining longevity Living a long, healthy life is everyone’s wish, but it is not an easy one to achieve. Many aging studies are developing strategies to increase health spans, the period of life spent with good health, without chronic diseases and disabilities. Researchers at KAIST presented new insights for improving the health span by just regulating the acti

2021-11-19 -

research The Dynamic Tracking of Tissue-Specific Secretory Proteins

Researchers develop a versatile and powerful tool for studying the spatiotemporal dynamics of secretory proteins, a valuable class of biomarkers and therapeutic targets Researchers have presented a method for profiling tissue-specific secretory proteins in live mice. This method is expected to be applicable to various tissues or disease models for investigating biomarkers or therapeutic targets involved in disease progression. This research was reported in Nature Communications on September 1

2021-09-14 -

research Mystery Solved with Math: Cytoplasmic Traffic Jam Disrupts Sleep-Wake Cycles

KAIST mathematicians and their collaborators at Florida State University have identified the principle of how aging and diseases like dementia and obesity cause sleep disorders. A combination of mathematical modelling and experiments demonstrated that the cytoplasmic congestion caused by aging, dementia, and/or obesity disrupts the circadian rhythms in the human body and leads to irregular sleep-wake cycles. This finding suggests new treatment strategies for addressing unstable sleep-wake cycles

2020-12-11