Nature

-

A Comprehensive Review of Biosynthesis of Inorganic Nanomaterials Using Microorganisms and Bacteriophages

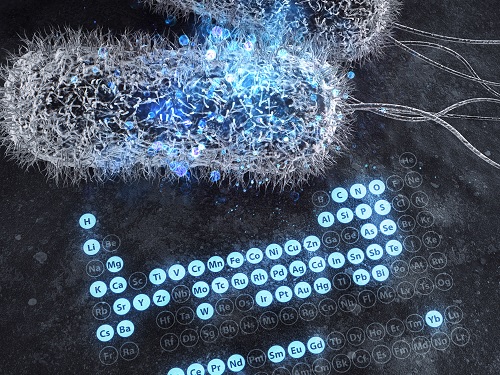

There are diverse methods for producing numerous inorganic nanomaterials involving many experimental variables. Among the numerous possible matches, finding the best pair for synthesizing in an environmentally friendly way has been a longstanding challenge for researchers and industries.

A KAIST bioprocess engineering research team led by Distinguished Professor Sang Yup Lee conducted a summary of 146 biosynthesized single and multi-element inorganic nanomaterials covering 55 elements in the periodic table synthesized using wild-type and genetically engineered microorganisms. Their research highlights the diverse applications of biogenic nanomaterials and gives strategies for improving the biosynthesis of nanomaterials in terms of their producibility, crystallinity, size, and shape.

The research team described a 10-step flow chart for developing the biosynthesis of inorganic nanomaterials using microorganisms and bacteriophages. The research was published at Nature Review Chemistry as a cover and hero paper on December 3.

“We suggest general strategies for microbial nanomaterial biosynthesis via a step-by-step flow chart and give our perspectives on the future of nanomaterial biosynthesis and applications. This flow chart will serve as a general guide for those wishing to prepare biosynthetic inorganic nanomaterials using microbial cells,” explained Dr.Yoojin Choi, a co-author of this research.

Most inorganic nanomaterials are produced using physical and chemical methods and biological synthesis has been gaining more and more attention. However, conventional synthesis processes have drawbacks in terms of high energy consumption and non-environmentally friendly processes. Meanwhile, microorganisms such as microalgae, yeasts, fungi, bacteria, and even viruses can be utilized as biofactories to produce single and multi-element inorganic nanomaterials under mild conditions.

After conducting a massive survey, the research team summed up that the development of genetically engineered microorganisms with increased inorganic-ion-binding affinity, inorganic-ion-reduction ability, and nanomaterial biosynthetic efficiency has enabled the synthesis of many inorganic nanomaterials.

Among the strategies, the team introduced their analysis of a Pourbaix diagram for controlling the size and morphology of a product. The research team said this Pourbaix diagram analysis can be widely employed for biosynthesizing new nanomaterials with industrial applications.Professor Sang Yup Lee added, “This research provides extensive information and perspectives on the biosynthesis of diverse inorganic nanomaterials using microorganisms and bacteriophages and their applications. We expect that biosynthetic inorganic nanomaterials will find more diverse and innovative applications across diverse fields of science and technology.”

Dr. Choi started this research in 2018 and her interview about completing this extensive research was featured in an article at Nature Career article on December 4.

-ProfileDistinguished Professor Sang Yup Lee leesy@kaist.ac.krMetabolic &Biomolecular Engineering National Research Laboratoryhttp://mbel.kaist.ac.krDepartment of Chemical and Biomolecular EngineeringKAIST

2020.12.07 View 11329

A Comprehensive Review of Biosynthesis of Inorganic Nanomaterials Using Microorganisms and Bacteriophages

There are diverse methods for producing numerous inorganic nanomaterials involving many experimental variables. Among the numerous possible matches, finding the best pair for synthesizing in an environmentally friendly way has been a longstanding challenge for researchers and industries.

A KAIST bioprocess engineering research team led by Distinguished Professor Sang Yup Lee conducted a summary of 146 biosynthesized single and multi-element inorganic nanomaterials covering 55 elements in the periodic table synthesized using wild-type and genetically engineered microorganisms. Their research highlights the diverse applications of biogenic nanomaterials and gives strategies for improving the biosynthesis of nanomaterials in terms of their producibility, crystallinity, size, and shape.

The research team described a 10-step flow chart for developing the biosynthesis of inorganic nanomaterials using microorganisms and bacteriophages. The research was published at Nature Review Chemistry as a cover and hero paper on December 3.

“We suggest general strategies for microbial nanomaterial biosynthesis via a step-by-step flow chart and give our perspectives on the future of nanomaterial biosynthesis and applications. This flow chart will serve as a general guide for those wishing to prepare biosynthetic inorganic nanomaterials using microbial cells,” explained Dr.Yoojin Choi, a co-author of this research.

Most inorganic nanomaterials are produced using physical and chemical methods and biological synthesis has been gaining more and more attention. However, conventional synthesis processes have drawbacks in terms of high energy consumption and non-environmentally friendly processes. Meanwhile, microorganisms such as microalgae, yeasts, fungi, bacteria, and even viruses can be utilized as biofactories to produce single and multi-element inorganic nanomaterials under mild conditions.

After conducting a massive survey, the research team summed up that the development of genetically engineered microorganisms with increased inorganic-ion-binding affinity, inorganic-ion-reduction ability, and nanomaterial biosynthetic efficiency has enabled the synthesis of many inorganic nanomaterials.

Among the strategies, the team introduced their analysis of a Pourbaix diagram for controlling the size and morphology of a product. The research team said this Pourbaix diagram analysis can be widely employed for biosynthesizing new nanomaterials with industrial applications.Professor Sang Yup Lee added, “This research provides extensive information and perspectives on the biosynthesis of diverse inorganic nanomaterials using microorganisms and bacteriophages and their applications. We expect that biosynthetic inorganic nanomaterials will find more diverse and innovative applications across diverse fields of science and technology.”

Dr. Choi started this research in 2018 and her interview about completing this extensive research was featured in an article at Nature Career article on December 4.

-ProfileDistinguished Professor Sang Yup Lee leesy@kaist.ac.krMetabolic &Biomolecular Engineering National Research Laboratoryhttp://mbel.kaist.ac.krDepartment of Chemical and Biomolecular EngineeringKAIST

2020.12.07 View 11329 -

Scientist of October: Professor Jungwon Kim

Professor Jungwon Kim from the Department of Mechanical Engineering was selected as the ‘Scientist of the Month’ for October 2020 by the Ministry of Science and ICT and the National Research Foundation of Korea. Professor Kim was recognized for his contributions to expanding the horizons of the basics of precision engineering through his research on multifunctional ultrahigh-speed, high-resolution sensors. He received 10 million KRW in prize money.

Professor Kim was selected as the recipient of this award in celebration of “Measurement Day”, which commemorates October 26 as the day in which King Sejong the Great established a volume measurement system.

Professor Kim discovered that the time difference between the pulse of light created by a laser and the pulse of the current produced by a light-emitting diode was as small as 100 attoseconds (10-16 seconds). He then developed a unique multifunctional ultrahigh-speed, high-resolution Time-of-Flight (TOF) sensor that could take measurements of multiple points at the same time by sampling electric light. The sensor, with a measurement speed of 100 megahertz (100 million vibrations per second), a resolution of 180 picometers (1/5.5 billion meters), and a dynamic range of 150 decibels, overcame the limitations of both existing TOF techniques and laser interferometric techniques at the same time. The results of this research were published in Nature Photonics on February 10, 2020.

Professor Kim said, “I’d like to thank the graduate students who worked passionately with me, and KAIST for providing an environment in which I could fully focus on research. I am looking forward to the new and diverse applications in the field of machine manufacturing, such as studying the dynamic phenomena in microdevices, or taking ultraprecision measurement of shapes for advanced manufacturing.”

(END)

2020.10.15 View 12313

Scientist of October: Professor Jungwon Kim

Professor Jungwon Kim from the Department of Mechanical Engineering was selected as the ‘Scientist of the Month’ for October 2020 by the Ministry of Science and ICT and the National Research Foundation of Korea. Professor Kim was recognized for his contributions to expanding the horizons of the basics of precision engineering through his research on multifunctional ultrahigh-speed, high-resolution sensors. He received 10 million KRW in prize money.

Professor Kim was selected as the recipient of this award in celebration of “Measurement Day”, which commemorates October 26 as the day in which King Sejong the Great established a volume measurement system.

Professor Kim discovered that the time difference between the pulse of light created by a laser and the pulse of the current produced by a light-emitting diode was as small as 100 attoseconds (10-16 seconds). He then developed a unique multifunctional ultrahigh-speed, high-resolution Time-of-Flight (TOF) sensor that could take measurements of multiple points at the same time by sampling electric light. The sensor, with a measurement speed of 100 megahertz (100 million vibrations per second), a resolution of 180 picometers (1/5.5 billion meters), and a dynamic range of 150 decibels, overcame the limitations of both existing TOF techniques and laser interferometric techniques at the same time. The results of this research were published in Nature Photonics on February 10, 2020.

Professor Kim said, “I’d like to thank the graduate students who worked passionately with me, and KAIST for providing an environment in which I could fully focus on research. I am looking forward to the new and diverse applications in the field of machine manufacturing, such as studying the dynamic phenomena in microdevices, or taking ultraprecision measurement of shapes for advanced manufacturing.”

(END)

2020.10.15 View 12313 -

Every Moment of Ultrafast Chemical Bonding Now Captured on Film

- The emerging moment of bond formation, two separate bonding steps, and subsequent vibrational motions were visualized. -

< Emergence of molecular vibrations and the evolution to covalent bonds observed in the research. Video Credit: KEK IMSS >

A team of South Korean researchers led by Professor Hyotcherl Ihee from the Department of Chemistry at KAIST reported the direct observation of the birthing moment of chemical bonds by tracking real-time atomic positions in the molecule. Professor Ihee, who also serves as Associate Director of the Center for Nanomaterials and Chemical Reactions at the Institute for Basic Science (IBS), conducted this study in collaboration with scientists at the Institute of Materials Structure Science of High Energy Accelerator Research Organization (KEK IMSS, Japan), RIKEN (Japan), and Pohang Accelerator Laboratory (PAL, South Korea). This work was published in Nature on June 24.

Targeted cancer drugs work by striking a tight bond between cancer cell and specific molecular targets that are involved in the growth and spread of cancer. Detailed images of such chemical bonding sites or pathways can provide key information necessary for maximizing the efficacy of oncogene treatments. However, atomic movements in a molecule have never been captured in the middle of the action, not even for an extremely simple molecule such as a triatomic molecule, made of only three atoms.

Professor Ihee's group and their international collaborators finally succeeded in capturing the ongoing reaction process of the chemical bond formation in the gold trimer. "The femtosecond-resolution images revealed that such molecular events took place in two separate stages, not simultaneously as previously assumed," says Professor Ihee, the corresponding author of the study. "The atoms in the gold trimer complex atoms remain in motion even after the chemical bonding is complete. The distance between the atoms increased and decreased periodically, exhibiting the molecular vibration. These visualized molecular vibrations allowed us to name the characteristic motion of each observed vibrational mode." adds Professor Ihee.

Atoms move extremely fast at a scale of femtosecond (fs) ― quadrillionths (or millionths of a billionth) of a second. Its movement is minute in the level of angstrom equal to one ten-billionth of a meter. They are especially elusive during the transition state where reaction intermediates are transitioning from reactants to products in a flash. The KAIST-IBS research team made this experimentally challenging task possible by using femtosecond x-ray liquidography (solution scattering). This experimental technique combines laser photolysis and x-ray scattering techniques. When a laser pulse strikes the sample, X-rays scatter and initiate the chemical bond formation reaction in the gold trimer complex. Femtosecond x-ray pulses obtained from a special light source called an x-ray free-electron laser (XFEL) were used to interrogate the bond-forming process. The experiments were performed at two XFEL facilities (4th generation linear accelerator) that are PAL-XFEL in South Korea and SACLA in Japan, and this study was conducted in collaboration with researchers from KEK IMSS, PAL, RIKEN, and the Japan Synchrotron Radiation Research Institute (JASRI).

Scattered waves from each atom interfere with each other and thus their x-ray scattering images are characterized by specific travel directions. The KAIST-IBS research team traced real-time positions of the three gold atoms over time by analyzing x-ray scattering images, which are determined by a three-dimensional structure of a molecule. Structural changes in the molecule complex resulted in multiple characteristic scattering images over time. When a molecule is excited by a laser pulse, multiple vibrational quantum states are simultaneously excited. The superposition of several excited vibrational quantum states is called a wave packet. The researchers tracked the wave packet in three-dimensional nuclear coordinates and found that the first half round of chemical bonding was formed within 35 fs after photoexcitation. The second half of the reaction followed within 360 fs to complete the entire reaction dynamics.

They also accurately illustrated molecular vibration motions in both temporal- and spatial-wise. This is quite a remarkable feat considering that such an ultrafast speed and a minute length of motion are quite challenging conditions for acquiring precise experimental data.

In this study, the KAIST-IBS research team improved upon their 2015 study published by Nature. In the previous study in 2015, the speed of the x-ray camera (time resolution) was limited to 500 fs, and the molecular structure had already changed to be linear with two chemical bonds within 500 fs. In this study, the progress of the bond formation and bent-to-linear structural transformation could be observed in real time, thanks to the improvement time resolution down to 100 fs. Thereby, the asynchronous bond formation mechanism in which two chemical bonds are formed in 35 fs and 360 fs, respectively, and the bent-to-linear transformation completed in 335 fs were visualized. In short, in addition to observing the beginning and end of chemical reactions, they reported every moment of the intermediate, ongoing rearrangement of nuclear configurations with dramatically improved experimental and analytical methods.

They will push this method of 'real-time tracking of atomic positions in a molecule and molecular vibration using femtosecond x-ray scattering' to reveal the mechanisms of organic and inorganic catalytic reactions and reactions involving proteins in the human body. "By directly tracking the molecular vibrations and real-time positions of all atoms in a molecule in the middle of reaction, we will be able to uncover mechanisms of various unknown organic and inorganic catalytic reactions and biochemical reactions," notes Dr. Jong Goo Kim, the lead author of the study.

Publications:

Kim, J. G., et al. (2020) ‘Mapping the emergence of molecular vibrations mediating bond formation’. Nature. Volume 582. Page 520-524. Available online at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2417-3

Profile: Hyotcherl Ihee, Ph.D.

Professor

hyotcherl.ihee@kaist.ac.kr

http://time.kaist.ac.kr/

Ihee Laboratory

Department of Chemistry

KAIST

https://www.kaist.ac.kr

Daejeon 34141, Korea

(END)

2020.06.24 View 18174

Every Moment of Ultrafast Chemical Bonding Now Captured on Film

- The emerging moment of bond formation, two separate bonding steps, and subsequent vibrational motions were visualized. -

< Emergence of molecular vibrations and the evolution to covalent bonds observed in the research. Video Credit: KEK IMSS >

A team of South Korean researchers led by Professor Hyotcherl Ihee from the Department of Chemistry at KAIST reported the direct observation of the birthing moment of chemical bonds by tracking real-time atomic positions in the molecule. Professor Ihee, who also serves as Associate Director of the Center for Nanomaterials and Chemical Reactions at the Institute for Basic Science (IBS), conducted this study in collaboration with scientists at the Institute of Materials Structure Science of High Energy Accelerator Research Organization (KEK IMSS, Japan), RIKEN (Japan), and Pohang Accelerator Laboratory (PAL, South Korea). This work was published in Nature on June 24.

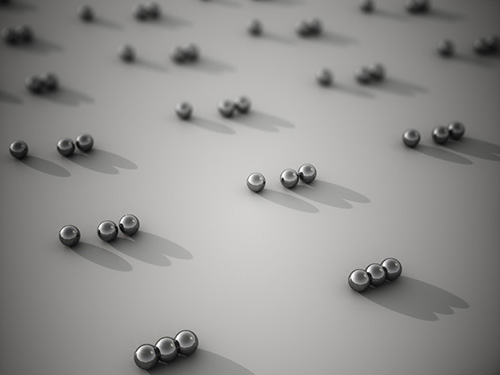

Targeted cancer drugs work by striking a tight bond between cancer cell and specific molecular targets that are involved in the growth and spread of cancer. Detailed images of such chemical bonding sites or pathways can provide key information necessary for maximizing the efficacy of oncogene treatments. However, atomic movements in a molecule have never been captured in the middle of the action, not even for an extremely simple molecule such as a triatomic molecule, made of only three atoms.

Professor Ihee's group and their international collaborators finally succeeded in capturing the ongoing reaction process of the chemical bond formation in the gold trimer. "The femtosecond-resolution images revealed that such molecular events took place in two separate stages, not simultaneously as previously assumed," says Professor Ihee, the corresponding author of the study. "The atoms in the gold trimer complex atoms remain in motion even after the chemical bonding is complete. The distance between the atoms increased and decreased periodically, exhibiting the molecular vibration. These visualized molecular vibrations allowed us to name the characteristic motion of each observed vibrational mode." adds Professor Ihee.

Atoms move extremely fast at a scale of femtosecond (fs) ― quadrillionths (or millionths of a billionth) of a second. Its movement is minute in the level of angstrom equal to one ten-billionth of a meter. They are especially elusive during the transition state where reaction intermediates are transitioning from reactants to products in a flash. The KAIST-IBS research team made this experimentally challenging task possible by using femtosecond x-ray liquidography (solution scattering). This experimental technique combines laser photolysis and x-ray scattering techniques. When a laser pulse strikes the sample, X-rays scatter and initiate the chemical bond formation reaction in the gold trimer complex. Femtosecond x-ray pulses obtained from a special light source called an x-ray free-electron laser (XFEL) were used to interrogate the bond-forming process. The experiments were performed at two XFEL facilities (4th generation linear accelerator) that are PAL-XFEL in South Korea and SACLA in Japan, and this study was conducted in collaboration with researchers from KEK IMSS, PAL, RIKEN, and the Japan Synchrotron Radiation Research Institute (JASRI).

Scattered waves from each atom interfere with each other and thus their x-ray scattering images are characterized by specific travel directions. The KAIST-IBS research team traced real-time positions of the three gold atoms over time by analyzing x-ray scattering images, which are determined by a three-dimensional structure of a molecule. Structural changes in the molecule complex resulted in multiple characteristic scattering images over time. When a molecule is excited by a laser pulse, multiple vibrational quantum states are simultaneously excited. The superposition of several excited vibrational quantum states is called a wave packet. The researchers tracked the wave packet in three-dimensional nuclear coordinates and found that the first half round of chemical bonding was formed within 35 fs after photoexcitation. The second half of the reaction followed within 360 fs to complete the entire reaction dynamics.

They also accurately illustrated molecular vibration motions in both temporal- and spatial-wise. This is quite a remarkable feat considering that such an ultrafast speed and a minute length of motion are quite challenging conditions for acquiring precise experimental data.

In this study, the KAIST-IBS research team improved upon their 2015 study published by Nature. In the previous study in 2015, the speed of the x-ray camera (time resolution) was limited to 500 fs, and the molecular structure had already changed to be linear with two chemical bonds within 500 fs. In this study, the progress of the bond formation and bent-to-linear structural transformation could be observed in real time, thanks to the improvement time resolution down to 100 fs. Thereby, the asynchronous bond formation mechanism in which two chemical bonds are formed in 35 fs and 360 fs, respectively, and the bent-to-linear transformation completed in 335 fs were visualized. In short, in addition to observing the beginning and end of chemical reactions, they reported every moment of the intermediate, ongoing rearrangement of nuclear configurations with dramatically improved experimental and analytical methods.

They will push this method of 'real-time tracking of atomic positions in a molecule and molecular vibration using femtosecond x-ray scattering' to reveal the mechanisms of organic and inorganic catalytic reactions and reactions involving proteins in the human body. "By directly tracking the molecular vibrations and real-time positions of all atoms in a molecule in the middle of reaction, we will be able to uncover mechanisms of various unknown organic and inorganic catalytic reactions and biochemical reactions," notes Dr. Jong Goo Kim, the lead author of the study.

Publications:

Kim, J. G., et al. (2020) ‘Mapping the emergence of molecular vibrations mediating bond formation’. Nature. Volume 582. Page 520-524. Available online at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2417-3

Profile: Hyotcherl Ihee, Ph.D.

Professor

hyotcherl.ihee@kaist.ac.kr

http://time.kaist.ac.kr/

Ihee Laboratory

Department of Chemistry

KAIST

https://www.kaist.ac.kr

Daejeon 34141, Korea

(END)

2020.06.24 View 18174 -

A Deep-Learned E-Skin Decodes Complex Human Motion

A deep-learning powered single-strained electronic skin sensor can capture human motion from a distance. The single strain sensor placed on the wrist decodes complex five-finger motions in real time with a virtual 3D hand that mirrors the original motions. The deep neural network boosted by rapid situation learning (RSL) ensures stable operation regardless of its position on the surface of the skin.

Conventional approaches require many sensor networks that cover the entire curvilinear surfaces of the target area. Unlike conventional wafer-based fabrication, this laser fabrication provides a new sensing paradigm for motion tracking.

The research team, led by Professor Sungho Jo from the School of Computing, collaborated with Professor Seunghwan Ko from Seoul National University to design this new measuring system that extracts signals corresponding to multiple finger motions by generating cracks in metal nanoparticle films using laser technology. The sensor patch was then attached to a user’s wrist to detect the movement of the fingers.

The concept of this research started from the idea that pinpointing a single area would be more efficient for identifying movements than affixing sensors to every joint and muscle. To make this targeting strategy work, it needs to accurately capture the signals from different areas at the point where they all converge, and then decoupling the information entangled in the converged signals. To maximize users’ usability and mobility, the research team used a single-channeled sensor to generate the signals corresponding to complex hand motions.

The rapid situation learning (RSL) system collects data from arbitrary parts on the wrist and automatically trains the model in a real-time demonstration with a virtual 3D hand that mirrors the original motions. To enhance the sensitivity of the sensor, researchers used laser-induced nanoscale cracking.

This sensory system can track the motion of the entire body with a small sensory network and facilitate the indirect remote measurement of human motions, which is applicable for wearable VR/AR systems.

The research team said they focused on two tasks while developing the sensor. First, they analyzed the sensor signal patterns into a latent space encapsulating temporal sensor behavior and then they mapped the latent vectors to finger motion metric spaces.

Professor Jo said, “Our system is expandable to other body parts. We already confirmed that the sensor is also capable of extracting gait motions from a pelvis. This technology is expected to provide a turning point in health-monitoring, motion tracking, and soft robotics.”

This study was featured in Nature Communications.

Publication:

Kim, K. K., et al. (2020) A deep-learned skin sensor decoding the epicentral human motions. Nature Communications. 11. 2149. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16040-y29

Link to download the full-text paper:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-020-16040-y.pdf

Profile: Professor Sungho Jo

shjo@kaist.ac.kr

http://nmail.kaist.ac.kr

Neuro-Machine Augmented Intelligence Lab

School of Computing

College of Engineering

KAIST

2020.06.10 View 12990

A Deep-Learned E-Skin Decodes Complex Human Motion

A deep-learning powered single-strained electronic skin sensor can capture human motion from a distance. The single strain sensor placed on the wrist decodes complex five-finger motions in real time with a virtual 3D hand that mirrors the original motions. The deep neural network boosted by rapid situation learning (RSL) ensures stable operation regardless of its position on the surface of the skin.

Conventional approaches require many sensor networks that cover the entire curvilinear surfaces of the target area. Unlike conventional wafer-based fabrication, this laser fabrication provides a new sensing paradigm for motion tracking.

The research team, led by Professor Sungho Jo from the School of Computing, collaborated with Professor Seunghwan Ko from Seoul National University to design this new measuring system that extracts signals corresponding to multiple finger motions by generating cracks in metal nanoparticle films using laser technology. The sensor patch was then attached to a user’s wrist to detect the movement of the fingers.

The concept of this research started from the idea that pinpointing a single area would be more efficient for identifying movements than affixing sensors to every joint and muscle. To make this targeting strategy work, it needs to accurately capture the signals from different areas at the point where they all converge, and then decoupling the information entangled in the converged signals. To maximize users’ usability and mobility, the research team used a single-channeled sensor to generate the signals corresponding to complex hand motions.

The rapid situation learning (RSL) system collects data from arbitrary parts on the wrist and automatically trains the model in a real-time demonstration with a virtual 3D hand that mirrors the original motions. To enhance the sensitivity of the sensor, researchers used laser-induced nanoscale cracking.

This sensory system can track the motion of the entire body with a small sensory network and facilitate the indirect remote measurement of human motions, which is applicable for wearable VR/AR systems.

The research team said they focused on two tasks while developing the sensor. First, they analyzed the sensor signal patterns into a latent space encapsulating temporal sensor behavior and then they mapped the latent vectors to finger motion metric spaces.

Professor Jo said, “Our system is expandable to other body parts. We already confirmed that the sensor is also capable of extracting gait motions from a pelvis. This technology is expected to provide a turning point in health-monitoring, motion tracking, and soft robotics.”

This study was featured in Nature Communications.

Publication:

Kim, K. K., et al. (2020) A deep-learned skin sensor decoding the epicentral human motions. Nature Communications. 11. 2149. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16040-y29

Link to download the full-text paper:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-020-16040-y.pdf

Profile: Professor Sungho Jo

shjo@kaist.ac.kr

http://nmail.kaist.ac.kr

Neuro-Machine Augmented Intelligence Lab

School of Computing

College of Engineering

KAIST

2020.06.10 View 12990 -

Researchers Present a Microbial Strain Capable of Massive Succinic Acid Production

A research team led by Distinguished Professor Sang Yup Lee reported the production of a microbial strain capable of the massive production of succinic acid with the highest production efficiency to date. This strategy of integrating systems metabolic engineering with enzyme engineering will be useful for the production of industrially competitive bio-based chemicals. Their strategy was described in Nature Communications on April 23.

The bio-based production of industrial chemicals from renewable non-food biomass has become increasingly important as a sustainable substitute for conventional petroleum-based production processes relying on fossil resources. Here, systems metabolic engineering, which is the key component for biorefinery technology, is utilized to effectively engineer the complex metabolic pathways of microorganisms to enable the efficient production of industrial chemicals.

Succinic acid, a four-carbon dicarboxylic acid, is one of the most promising platform chemicals serving as a precursor for industrially important chemicals. Among microorganisms producing succinic acid, Mannheimia succiniciproducens has been proven to be one of the best strains for succinic acid production.

The research team has developed a bio-based succinic acid production technology using the M. succiniciproducens strain isolated from the rumen of Korean cow for over 20 years and succeeded in developing a strain capable of producing succinic acid with the highest production efficiency.

They carried out systems metabolic engineering to optimize the succinic acid production pathway of the M. succiniciproducens strain by determining the crystal structure of key enzymes important for succinic acid production and performing protein engineering to develop enzymes with better catalytic performance.

As a result, 134 g per liter of succinic acid was produced from the fermentation of an engineered strain using glucose, glycerol, and carbon dioxide. They were able to achieve 21 g per liter per hour of succinic acid production, which is one of the key factors determining the economic feasibility of the overall production process. This is the world’s best succinic acid production efficiency reported to date. Previous production methods averaged 1~3 g per liter per hour.

Distinguished professor Sang Yup Lee explained that his team’s work will significantly contribute to transforming the current petrochemical-based industry into an eco-friendly bio-based one.

“Our research on the highly efficient bio-based production of succinic acid from renewable non-food resources and carbon dioxide has provided a basis for reducing our strong dependence on fossil resources, which is the main cause of the environmental crisis,” Professor Lee said.

This work was supported by the Technology Development Program to Solve Climate Changes via Systems Metabolic Engineering for Biorefineries and the C1 Gas Refinery Program from the Ministry of Science and ICT through the National Research Foundation of Korea.

2020.05.06 View 9983

Researchers Present a Microbial Strain Capable of Massive Succinic Acid Production

A research team led by Distinguished Professor Sang Yup Lee reported the production of a microbial strain capable of the massive production of succinic acid with the highest production efficiency to date. This strategy of integrating systems metabolic engineering with enzyme engineering will be useful for the production of industrially competitive bio-based chemicals. Their strategy was described in Nature Communications on April 23.

The bio-based production of industrial chemicals from renewable non-food biomass has become increasingly important as a sustainable substitute for conventional petroleum-based production processes relying on fossil resources. Here, systems metabolic engineering, which is the key component for biorefinery technology, is utilized to effectively engineer the complex metabolic pathways of microorganisms to enable the efficient production of industrial chemicals.

Succinic acid, a four-carbon dicarboxylic acid, is one of the most promising platform chemicals serving as a precursor for industrially important chemicals. Among microorganisms producing succinic acid, Mannheimia succiniciproducens has been proven to be one of the best strains for succinic acid production.

The research team has developed a bio-based succinic acid production technology using the M. succiniciproducens strain isolated from the rumen of Korean cow for over 20 years and succeeded in developing a strain capable of producing succinic acid with the highest production efficiency.

They carried out systems metabolic engineering to optimize the succinic acid production pathway of the M. succiniciproducens strain by determining the crystal structure of key enzymes important for succinic acid production and performing protein engineering to develop enzymes with better catalytic performance.

As a result, 134 g per liter of succinic acid was produced from the fermentation of an engineered strain using glucose, glycerol, and carbon dioxide. They were able to achieve 21 g per liter per hour of succinic acid production, which is one of the key factors determining the economic feasibility of the overall production process. This is the world’s best succinic acid production efficiency reported to date. Previous production methods averaged 1~3 g per liter per hour.

Distinguished professor Sang Yup Lee explained that his team’s work will significantly contribute to transforming the current petrochemical-based industry into an eco-friendly bio-based one.

“Our research on the highly efficient bio-based production of succinic acid from renewable non-food resources and carbon dioxide has provided a basis for reducing our strong dependence on fossil resources, which is the main cause of the environmental crisis,” Professor Lee said.

This work was supported by the Technology Development Program to Solve Climate Changes via Systems Metabolic Engineering for Biorefineries and the C1 Gas Refinery Program from the Ministry of Science and ICT through the National Research Foundation of Korea.

2020.05.06 View 9983 -

Scientists Observe the Elusive Kondo Screening Cloud

Scientists ended a 50-year quest by directly observing a quantum phenomenon

An international research group of Professor Heung-Sun Sim has ended a 50-year quest by directly observing a quantum phenomenon known as a Kondo screening cloud. This research, published in Nature on March 11, opens a novel way to engineer spin screening and entanglement. According to the research, the cloud can mediate interactions between distant spins confined in quantum dots, which is a necessary protocol for semiconductor spin-based quantum information processing. This spin-spin interaction mediated by the Kondo cloud is unique since both its strength and sign (two spins favor either parallel or anti-parallel configuration) are electrically tunable, while conventional schemes cannot reverse the sign.

This phenomenon, which is important for many physical phenomena such as dilute magnetic impurities and spin glasses, is essentially a cloud that masks magnetic impurities in a material. It was known to exist but its spatial extension had never been observed, creating controversy over whether such an extension actually existed.

Magnetism arises from a property of electrons known as spin, meaning that they have angular momentum aligned in one of either two directions, conventionally known as up and down. However, due to a phenomenon known as the Kondo effect, the spins of conduction electrons—the electrons that flow freely in a material—become entangled with a localized magnetic impurity, and effectively screen it. The strength of this spin coupling, calibrated as a temperature, is known as the Kondo temperature.

The size of the cloud is another important parameter for a material containing multiple magnetic impurities because the spins in the cloud couple with one another and mediate the coupling between magnetic impurities when the clouds overlap. This happens in various materials such as Kondo lattices, spin glasses, and high temperature superconductors.

Although the Kondo effect for a single magnetic impurity is now a text-book subject in many-body physics, detection of its key object, the Kondo cloud and its length, has remained elusive despite many attempts during the past five decades. Experiments using nuclear magnetic resonance or scanning tunneling microscopy, two common methods for understanding the structure of matter, have either shown no signature of the cloud, or demonstrated a signature only at a very short distance, less than 1 nanometer, so much shorter than the predicted cloud size, which was in the micron range.

In the present study, the authors observed a Kondo screening cloud formed by an impurity defined as a localized electron spin in a quantum dot—a type of “artificial atom”—coupled to quasi-one-dimensional conduction electrons, and then used an interferometer to measure changes in the Kondo temperature, allowing them to investigate the presence of a cloud at the interferometer end.

Essentially, they slightly perturbed the conduction electrons at a location away from the quantum dot using an electrostatic gate. The wave of conducting electrons scattered by this perturbation returned back to the quantum dot and interfered with itself. This is similar to how a wave on a water surface being scattered by a wall forms a stripe pattern. The Kondo cloud is a quantum mechanical object which acts to preserve the wave nature of electrons inside the cloud.

Even though there is no direct electrostatic influence of the perturbation on the quantum dot, this interference modifies the Kondo signature measured by electron conductance through the quantum dot if the perturbation is present inside the cloud. In the study, the researchers found that the length as well as the shape of the cloud is universally scaled by the inverse of the Kondo temperature, and that the cloud’s size and shape were in good agreement with theoretical calculations.

Professor Sim at the Department of Physics proposed the method for detecting the Kondo cloud in the co-research with the RIKEN Center for Emergent Matter Science, the City University of Hong Kong, the University of Tokyo, and Ruhr University Bochum in Germany.

Professor Sim said, “The observed spin cloud is a micrometer-size object that has quantum mechanical wave nature and entanglement. This is why the spin cloud has not been observed despite a long search. It is remarkable in a fundamental and technical point of view that such a large quantum object can now be created, controlled, and detected.

Dr. Michihisa Yamamoto of the RIKEN Center for Emergent Matter Science also said, “It is very satisfying to have been able to obtain real space image of the Kondo cloud, as it is a real breakthrough for understanding various systems containing multiple magnetic impurities. The size of the Kondo cloud in semiconductors was found to be much larger than the typical size of semiconductor devices.”

Publication:

Borzenets et al. (2020) Observation of the Kondo screening cloud. Nature, 579. pp.210-213. Available online at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2058-6

Profile:

Heung-Sun Sim, PhD

Professor

hssim@kaist.ac.kr

https://qet.kaist.ac.kr/

Quantum Electron Correlation & Transport Theory Group (QECT Lab)

https://qc.kaist.ac.kr/index.php/group1/

Center for Quantum Coherence In COndensed Matter

Department of Physics

https://www.kaist.ac.kr

Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST)

Daejeon, Republic of Korea

2020.03.13 View 16358

Scientists Observe the Elusive Kondo Screening Cloud

Scientists ended a 50-year quest by directly observing a quantum phenomenon

An international research group of Professor Heung-Sun Sim has ended a 50-year quest by directly observing a quantum phenomenon known as a Kondo screening cloud. This research, published in Nature on March 11, opens a novel way to engineer spin screening and entanglement. According to the research, the cloud can mediate interactions between distant spins confined in quantum dots, which is a necessary protocol for semiconductor spin-based quantum information processing. This spin-spin interaction mediated by the Kondo cloud is unique since both its strength and sign (two spins favor either parallel or anti-parallel configuration) are electrically tunable, while conventional schemes cannot reverse the sign.

This phenomenon, which is important for many physical phenomena such as dilute magnetic impurities and spin glasses, is essentially a cloud that masks magnetic impurities in a material. It was known to exist but its spatial extension had never been observed, creating controversy over whether such an extension actually existed.

Magnetism arises from a property of electrons known as spin, meaning that they have angular momentum aligned in one of either two directions, conventionally known as up and down. However, due to a phenomenon known as the Kondo effect, the spins of conduction electrons—the electrons that flow freely in a material—become entangled with a localized magnetic impurity, and effectively screen it. The strength of this spin coupling, calibrated as a temperature, is known as the Kondo temperature.

The size of the cloud is another important parameter for a material containing multiple magnetic impurities because the spins in the cloud couple with one another and mediate the coupling between magnetic impurities when the clouds overlap. This happens in various materials such as Kondo lattices, spin glasses, and high temperature superconductors.

Although the Kondo effect for a single magnetic impurity is now a text-book subject in many-body physics, detection of its key object, the Kondo cloud and its length, has remained elusive despite many attempts during the past five decades. Experiments using nuclear magnetic resonance or scanning tunneling microscopy, two common methods for understanding the structure of matter, have either shown no signature of the cloud, or demonstrated a signature only at a very short distance, less than 1 nanometer, so much shorter than the predicted cloud size, which was in the micron range.

In the present study, the authors observed a Kondo screening cloud formed by an impurity defined as a localized electron spin in a quantum dot—a type of “artificial atom”—coupled to quasi-one-dimensional conduction electrons, and then used an interferometer to measure changes in the Kondo temperature, allowing them to investigate the presence of a cloud at the interferometer end.

Essentially, they slightly perturbed the conduction electrons at a location away from the quantum dot using an electrostatic gate. The wave of conducting electrons scattered by this perturbation returned back to the quantum dot and interfered with itself. This is similar to how a wave on a water surface being scattered by a wall forms a stripe pattern. The Kondo cloud is a quantum mechanical object which acts to preserve the wave nature of electrons inside the cloud.

Even though there is no direct electrostatic influence of the perturbation on the quantum dot, this interference modifies the Kondo signature measured by electron conductance through the quantum dot if the perturbation is present inside the cloud. In the study, the researchers found that the length as well as the shape of the cloud is universally scaled by the inverse of the Kondo temperature, and that the cloud’s size and shape were in good agreement with theoretical calculations.

Professor Sim at the Department of Physics proposed the method for detecting the Kondo cloud in the co-research with the RIKEN Center for Emergent Matter Science, the City University of Hong Kong, the University of Tokyo, and Ruhr University Bochum in Germany.

Professor Sim said, “The observed spin cloud is a micrometer-size object that has quantum mechanical wave nature and entanglement. This is why the spin cloud has not been observed despite a long search. It is remarkable in a fundamental and technical point of view that such a large quantum object can now be created, controlled, and detected.

Dr. Michihisa Yamamoto of the RIKEN Center for Emergent Matter Science also said, “It is very satisfying to have been able to obtain real space image of the Kondo cloud, as it is a real breakthrough for understanding various systems containing multiple magnetic impurities. The size of the Kondo cloud in semiconductors was found to be much larger than the typical size of semiconductor devices.”

Publication:

Borzenets et al. (2020) Observation of the Kondo screening cloud. Nature, 579. pp.210-213. Available online at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2058-6

Profile:

Heung-Sun Sim, PhD

Professor

hssim@kaist.ac.kr

https://qet.kaist.ac.kr/

Quantum Electron Correlation & Transport Theory Group (QECT Lab)

https://qc.kaist.ac.kr/index.php/group1/

Center for Quantum Coherence In COndensed Matter

Department of Physics

https://www.kaist.ac.kr

Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST)

Daejeon, Republic of Korea

2020.03.13 View 16358 -

Blood-Based Multiplexed Diagnostic Sensor Helps to Accurately Detect Alzheimer’s Disease

A research team at KAIST reported clinically accurate multiplexed electrical biosensor for detecting Alzheimer’s disease by measuring its core biomarkers using densely aligned carbon nanotubes.

Alzheimer’s disease is the most prevalent neurodegenerative disorder, affecting one in ten aged over 65 years. Early diagnosis can reduce the risk of suffering the disease by one-third, according to recent reports. However, its early diagnosis remains challenging due to the low accuracy but high cost of diagnosis.

Research team led by Professors Chan Beum Park and Steve Park described an ultrasensitive detection of multiple Alzheimer's disease core biomarker in human plasma. The team have designed the sensor array by employing a densely aligned single-walled carbon nanotube thin films as a transducer.

The representative biomarkers of Alzheimer's disease are beta-amyloid42, beta-amyloid40, total tau protein, phosphorylated tau protein and the concentrations of these biomarkers in human plasma are directly correlated with the pathology of Alzheimer’s disease.

The research team developed a highly sensitive resistive biosensor based on densely aligned carbon nanotubes fabricated by Langmuir-Blodgett method with a low manufacturing cost.

Aligned carbon nanotubes with high density minimizes the tube-to-tube junction resistance compared with randomly distributed carbon nanotubes, which leads to the improvement of sensor sensitivity. To be more specific, this resistive sensor with densely aligned carbon nanotubes exhibits a sensitivity over 100 times higher than that of conventional carbon nanotube-based biosensors.

By measuring the concentrations of four Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers simultaneously Alzheimer patients can be discriminated from health controls with an average sensitivity of 90.0%, a selectivity of 90.0% and an average accuracy of 88.6%.

This work, titled “Clinically accurate diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease via multiplexed sensing of core biomarkers in human plasma”, were published in Nature Communications on January 8th 2020. The authors include PhD candidate Kayoung Kim and MS candidate Min-Ji Kim.

Professor Steve Park said, “This study was conducted on patients who are already confirmed with Alzheimer’s Disease. For further use in practical setting, it is necessary to test the patients with mild cognitive impairment.” He also emphasized that, “It is essential to establish a nationwide infrastructure, such as mild cognitive impairment cohort study and a dementia cohort study. This would enable the establishment of world-wide research network, and will help various private and public institutions.”

This research was supported by the Ministry of Science and ICT, Human Resource Bank of Chungnam National University Hospital and Chungbuk National University Hospital.

< A schematic diagram of a high-density aligned carbon nanotube-based resistive sensor that distinguishes patients with Alzheimer’s Disease by measuring the concentration of four biomarkers in the blood. >

Profile:

Professor Steve Park

stevepark@kaist.ac.kr

Department of Materials Science and Engineering

http://steveparklab.kaist.ac.kr/

KAIST

Profile:

Professor Chan Beum Park

parkcb at kaist.ac.kr

Department of Materials Science and Engineering

http://biomaterials.kaist.ac.kr/

KAIST

2020.02.07 View 11312

Blood-Based Multiplexed Diagnostic Sensor Helps to Accurately Detect Alzheimer’s Disease

A research team at KAIST reported clinically accurate multiplexed electrical biosensor for detecting Alzheimer’s disease by measuring its core biomarkers using densely aligned carbon nanotubes.

Alzheimer’s disease is the most prevalent neurodegenerative disorder, affecting one in ten aged over 65 years. Early diagnosis can reduce the risk of suffering the disease by one-third, according to recent reports. However, its early diagnosis remains challenging due to the low accuracy but high cost of diagnosis.

Research team led by Professors Chan Beum Park and Steve Park described an ultrasensitive detection of multiple Alzheimer's disease core biomarker in human plasma. The team have designed the sensor array by employing a densely aligned single-walled carbon nanotube thin films as a transducer.

The representative biomarkers of Alzheimer's disease are beta-amyloid42, beta-amyloid40, total tau protein, phosphorylated tau protein and the concentrations of these biomarkers in human plasma are directly correlated with the pathology of Alzheimer’s disease.

The research team developed a highly sensitive resistive biosensor based on densely aligned carbon nanotubes fabricated by Langmuir-Blodgett method with a low manufacturing cost.

Aligned carbon nanotubes with high density minimizes the tube-to-tube junction resistance compared with randomly distributed carbon nanotubes, which leads to the improvement of sensor sensitivity. To be more specific, this resistive sensor with densely aligned carbon nanotubes exhibits a sensitivity over 100 times higher than that of conventional carbon nanotube-based biosensors.

By measuring the concentrations of four Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers simultaneously Alzheimer patients can be discriminated from health controls with an average sensitivity of 90.0%, a selectivity of 90.0% and an average accuracy of 88.6%.

This work, titled “Clinically accurate diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease via multiplexed sensing of core biomarkers in human plasma”, were published in Nature Communications on January 8th 2020. The authors include PhD candidate Kayoung Kim and MS candidate Min-Ji Kim.

Professor Steve Park said, “This study was conducted on patients who are already confirmed with Alzheimer’s Disease. For further use in practical setting, it is necessary to test the patients with mild cognitive impairment.” He also emphasized that, “It is essential to establish a nationwide infrastructure, such as mild cognitive impairment cohort study and a dementia cohort study. This would enable the establishment of world-wide research network, and will help various private and public institutions.”

This research was supported by the Ministry of Science and ICT, Human Resource Bank of Chungnam National University Hospital and Chungbuk National University Hospital.

< A schematic diagram of a high-density aligned carbon nanotube-based resistive sensor that distinguishes patients with Alzheimer’s Disease by measuring the concentration of four biomarkers in the blood. >

Profile:

Professor Steve Park

stevepark@kaist.ac.kr

Department of Materials Science and Engineering

http://steveparklab.kaist.ac.kr/

KAIST

Profile:

Professor Chan Beum Park

parkcb at kaist.ac.kr

Department of Materials Science and Engineering

http://biomaterials.kaist.ac.kr/

KAIST

2020.02.07 View 11312 -

Scientists Discover the Mechanism of DNA High-Order Structure Formation

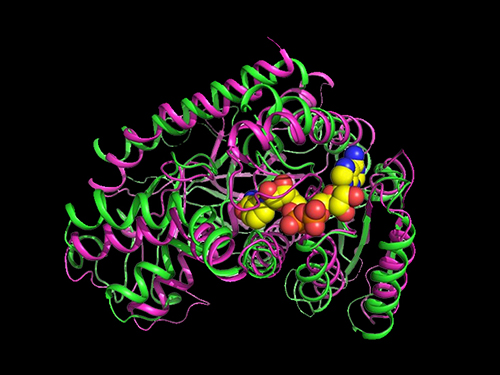

(Molecular structures of Abo1 in different energy states (left), Demonstration of an Abo1-assisted histone loading onto DNA by the DNA curtain assay. )

The genetic material of our cells—DNA—exists in a high-order structure called “chromatin”. Chromatin consists of DNA wrapped around histone proteins and efficiently packs DNA into a small volume. Moreover, using a spool and thread analogy, chromatin allows DNA to be locally wound or unwound, thus enabling genes to be enclosed or exposed. The misregulation of chromatin structures results in aberrant gene expression and can ultimately lead to developmental disorders or cancers. Despite the importance of DNA high-order structures, the complexity of the underlying machinery has circumvented molecular dissection.

For the first time, molecular biologists have uncovered how one particular mechanism uses energy to ensure proper histone placement onto DNA to form chromatin. They published their results on Dec. 17 in Nature Communications.

The study focused on proteins called histone chaperones. Histone chaperones are responsible for adding and removing specific histones at specific times during the DNA packaging process. The wrong histone at the wrong time and place could result in the misregulation of gene expression or aberrant DNA replication. Thus, histone chaperones are key players in the assembly and disassembly of chromatin.

“In order to carefully control the assembly and disassembly of chromatin units, histone chaperones act as molecular escorts that prevent histone aggregation and undesired interactions,” said Professor Ji-Joon Song in the Department of Biological Sciences at KAIST. “We set out to understand how a unique histone chaperone uses chemical energy to assemble or disassemble chromatin.”

Song and his team looked to Abo1, the only known histone chaperone that utilizes cellular energy (ATP). While Abo1 is found in yeast, it has an analogous partner in other organisms, including humans, called ATAD2. Both use ATP, which is produced through a cellular process where enzymes break down a molecule’s phosphate bond. ATP energy is typically used to power other cellular processes, but it is a rare partner for histone chaperones.

“This was an interesting problem in the field because all other histone chaperones studied to date do not use ATP,” Song said.

By imaging Abo1 with a single-molecule fluorescence imaging technique known as the DNA curtain assay, the researchers could examine the protein interactions at the single-molecule level. The technique allows scientists to arrange the DNA molecules and proteins on a single layer of a microfluidic chamber and examine the layer with fluorescence microscopy.

The researchers found through real-time observation that Abo1 is ring-shaped and changes its structure to accommodate a specific histone and deposit it on DNA. Moreover, they found that the accommodating structural changes are powered by ADP.

“We discovered a mechanism by which Abo1 accommodates histone substrates, ultimately allowing it to function as a unique energy-dependent histone chaperone,” Song said. “We also found that despite looking like a protein disassembly machine, Abo1 actually loads histone substrates onto DNA to facilitate chromatin assembly.”

The researchers plan to continue exploring how energy-dependent histone chaperones bind and release histones, with the ultimate goal of developing therapeutics that can target cancer-causing misbehavior by Abo1’s analogous human counterpart, ATAD2.

-Profile

Professor Ji-Joon Song

Department of Biological Sciences KI for the BioCentury (https://kis.kaist.ac.kr/index.php?mid=KIB_O) KAIST

2020.01.07 View 10892

Scientists Discover the Mechanism of DNA High-Order Structure Formation

(Molecular structures of Abo1 in different energy states (left), Demonstration of an Abo1-assisted histone loading onto DNA by the DNA curtain assay. )

The genetic material of our cells—DNA—exists in a high-order structure called “chromatin”. Chromatin consists of DNA wrapped around histone proteins and efficiently packs DNA into a small volume. Moreover, using a spool and thread analogy, chromatin allows DNA to be locally wound or unwound, thus enabling genes to be enclosed or exposed. The misregulation of chromatin structures results in aberrant gene expression and can ultimately lead to developmental disorders or cancers. Despite the importance of DNA high-order structures, the complexity of the underlying machinery has circumvented molecular dissection.

For the first time, molecular biologists have uncovered how one particular mechanism uses energy to ensure proper histone placement onto DNA to form chromatin. They published their results on Dec. 17 in Nature Communications.

The study focused on proteins called histone chaperones. Histone chaperones are responsible for adding and removing specific histones at specific times during the DNA packaging process. The wrong histone at the wrong time and place could result in the misregulation of gene expression or aberrant DNA replication. Thus, histone chaperones are key players in the assembly and disassembly of chromatin.

“In order to carefully control the assembly and disassembly of chromatin units, histone chaperones act as molecular escorts that prevent histone aggregation and undesired interactions,” said Professor Ji-Joon Song in the Department of Biological Sciences at KAIST. “We set out to understand how a unique histone chaperone uses chemical energy to assemble or disassemble chromatin.”

Song and his team looked to Abo1, the only known histone chaperone that utilizes cellular energy (ATP). While Abo1 is found in yeast, it has an analogous partner in other organisms, including humans, called ATAD2. Both use ATP, which is produced through a cellular process where enzymes break down a molecule’s phosphate bond. ATP energy is typically used to power other cellular processes, but it is a rare partner for histone chaperones.

“This was an interesting problem in the field because all other histone chaperones studied to date do not use ATP,” Song said.

By imaging Abo1 with a single-molecule fluorescence imaging technique known as the DNA curtain assay, the researchers could examine the protein interactions at the single-molecule level. The technique allows scientists to arrange the DNA molecules and proteins on a single layer of a microfluidic chamber and examine the layer with fluorescence microscopy.

The researchers found through real-time observation that Abo1 is ring-shaped and changes its structure to accommodate a specific histone and deposit it on DNA. Moreover, they found that the accommodating structural changes are powered by ADP.

“We discovered a mechanism by which Abo1 accommodates histone substrates, ultimately allowing it to function as a unique energy-dependent histone chaperone,” Song said. “We also found that despite looking like a protein disassembly machine, Abo1 actually loads histone substrates onto DNA to facilitate chromatin assembly.”

The researchers plan to continue exploring how energy-dependent histone chaperones bind and release histones, with the ultimate goal of developing therapeutics that can target cancer-causing misbehavior by Abo1’s analogous human counterpart, ATAD2.

-Profile

Professor Ji-Joon Song

Department of Biological Sciences KI for the BioCentury (https://kis.kaist.ac.kr/index.php?mid=KIB_O) KAIST

2020.01.07 View 10892 -

‘Carrier-Resolved Photo-Hall’ to Push Semiconductor Advances

(Professor Shin and Dr. Gunawan (left))

An IBM-KAIST research team described a breakthrough in a 140-year-old mystery in physics. The research reported in Nature last month unlocks the physical characteristics of semiconductors in much greater detail and aids in the development of new and improved semiconductor materials.

Research team under Professor Byungha Shin at the Department of Material Sciences and Engineering and Dr. Oki Gunawan at IBM discovered a new formula and technique that enables the simultaneous extraction of both majority and minority carrier information such as their density and mobility, as well as gain additional insights about carrier lifetimes, diffusion lengths, and the recombination process. This new discovery and technology will help push semiconductor advances in both existing and emerging technologies.

Semiconductors are the basic building blocks of today’s digital electronics age, providing us with a multitude of devices that benefit our modern life. To truly appreciate the physics of semiconductors, it is very important to understand the fundamental properties of the charge carriers inside the materials, whether those particles are positive or negative, their speed under an applied electric field, and how densely they are packed into the material.

Physicist Edwin Hall found a way to determine those properties in 1879, when he discovered that a magnetic field will deflect the movement of electronic charges inside a conductor and that the amount of deflection can be measured as a voltage perpendicular to the flow of the charge. Decades after Hall’s discovery, researchers also recognized that they can measure the Hall effect with light via “photo-Hall experiments”. During such experiments, the light generates multiple carriers or electron–hole pairs in the semiconductors.

Unfortunately, the basic Hall effect only provided insights into the dominant charge carrier (or majority carrier). Researchers were unable to extract the properties of both carriers (the majority and minority carriers) simultaneously. The property information of both carriers is crucial for many applications that involve light such as solar cells and other optoelectronic devices.

In the photo-Hall experiment by the KAIST-IBM team, both carriers contribute to changes in conductivity and the Hall coefficient. The key insight comes from measuring the conductivity and Hall coefficient as a function of light intensity. Hidden in the trajectory of the conductivity, the Hall coefficient curve reveals crucial new information: the difference in the mobility of both carriers. As discussed in the paper, this relationship can be expressed elegantly as: Δµ = d (σ²H)/dσ

The research team solved for both majority and minority carrier mobility and density as a function of light intensity, naming the new technique Carrier-Resolved Photo Hall (CRPH) measurement. With known light illumination intensity, the carrier lifetime can be established in a similar way.

Beyond advances in theoretical understanding, advances in experimental techniques were also critical for enabling this breakthrough. The technique requires a clean Hall signal measurement, which can be challenging for materials where the Hall signal is weak due to low mobility or when extra unwanted signals are present, such as under strong light illumination.

The newly developed photo-Hall technique allows the extraction of an astonishing amount of information from semiconductors. In contrast to only three parameters obtained in the classic Hall measurements, this new technique yields up to seven parameters at every tested level of light intensity. These include the mobility of both the electron and hole; their carrier density under light; the recombination lifetime; and the diffusion lengths for electrons, holes, and ambipolar types. All of these can be repeated N times (i.e. the number of light intensity settings used in the experiment).

Professor Shin said, “This novel technology sheds new light on understanding the physical characteristics of semiconductor materials in great detail.” Dr. Gunawan added, “This will will help accelerate the development of next-generation semiconductor technology such as better solar cells, better optoelectronics devices, and new materials and devices for artificial intelligence technology.”

Profile:

Professor Byungha Shin

Department of Materials Science and Engineering

KAIST

byungha@kaist.ac.kr

http://energymatlab.kaist.ac.kr/

2019.11.18 View 14698

‘Carrier-Resolved Photo-Hall’ to Push Semiconductor Advances

(Professor Shin and Dr. Gunawan (left))

An IBM-KAIST research team described a breakthrough in a 140-year-old mystery in physics. The research reported in Nature last month unlocks the physical characteristics of semiconductors in much greater detail and aids in the development of new and improved semiconductor materials.

Research team under Professor Byungha Shin at the Department of Material Sciences and Engineering and Dr. Oki Gunawan at IBM discovered a new formula and technique that enables the simultaneous extraction of both majority and minority carrier information such as their density and mobility, as well as gain additional insights about carrier lifetimes, diffusion lengths, and the recombination process. This new discovery and technology will help push semiconductor advances in both existing and emerging technologies.

Semiconductors are the basic building blocks of today’s digital electronics age, providing us with a multitude of devices that benefit our modern life. To truly appreciate the physics of semiconductors, it is very important to understand the fundamental properties of the charge carriers inside the materials, whether those particles are positive or negative, their speed under an applied electric field, and how densely they are packed into the material.

Physicist Edwin Hall found a way to determine those properties in 1879, when he discovered that a magnetic field will deflect the movement of electronic charges inside a conductor and that the amount of deflection can be measured as a voltage perpendicular to the flow of the charge. Decades after Hall’s discovery, researchers also recognized that they can measure the Hall effect with light via “photo-Hall experiments”. During such experiments, the light generates multiple carriers or electron–hole pairs in the semiconductors.

Unfortunately, the basic Hall effect only provided insights into the dominant charge carrier (or majority carrier). Researchers were unable to extract the properties of both carriers (the majority and minority carriers) simultaneously. The property information of both carriers is crucial for many applications that involve light such as solar cells and other optoelectronic devices.

In the photo-Hall experiment by the KAIST-IBM team, both carriers contribute to changes in conductivity and the Hall coefficient. The key insight comes from measuring the conductivity and Hall coefficient as a function of light intensity. Hidden in the trajectory of the conductivity, the Hall coefficient curve reveals crucial new information: the difference in the mobility of both carriers. As discussed in the paper, this relationship can be expressed elegantly as: Δµ = d (σ²H)/dσ

The research team solved for both majority and minority carrier mobility and density as a function of light intensity, naming the new technique Carrier-Resolved Photo Hall (CRPH) measurement. With known light illumination intensity, the carrier lifetime can be established in a similar way.

Beyond advances in theoretical understanding, advances in experimental techniques were also critical for enabling this breakthrough. The technique requires a clean Hall signal measurement, which can be challenging for materials where the Hall signal is weak due to low mobility or when extra unwanted signals are present, such as under strong light illumination.

The newly developed photo-Hall technique allows the extraction of an astonishing amount of information from semiconductors. In contrast to only three parameters obtained in the classic Hall measurements, this new technique yields up to seven parameters at every tested level of light intensity. These include the mobility of both the electron and hole; their carrier density under light; the recombination lifetime; and the diffusion lengths for electrons, holes, and ambipolar types. All of these can be repeated N times (i.e. the number of light intensity settings used in the experiment).

Professor Shin said, “This novel technology sheds new light on understanding the physical characteristics of semiconductor materials in great detail.” Dr. Gunawan added, “This will will help accelerate the development of next-generation semiconductor technology such as better solar cells, better optoelectronics devices, and new materials and devices for artificial intelligence technology.”

Profile:

Professor Byungha Shin

Department of Materials Science and Engineering

KAIST

byungha@kaist.ac.kr

http://energymatlab.kaist.ac.kr/

2019.11.18 View 14698 -

Ultrafast Quantum Motion in a Nanoscale Trap Detected

< Professor Heung-Sun Sim (left) and Co-author Dr. Sungguen Ryu (right) >

KAIST researchers have reported the detection of a picosecond electron motion in a silicon transistor. This study has presented a new protocol for measuring ultrafast electronic dynamics in an effective time-resolved fashion of picosecond resolution. The detection was made in collaboration with Nippon Telegraph and Telephone Corp. (NTT) in Japan and National Physical Laboratory (NPL) in the UK and is the first report to the best of our knowledge.

When an electron is captured in a nanoscale trap in solids, its quantum mechanical wave function can exhibit spatial oscillation at sub-terahertz frequencies. Time-resolved detection of such picosecond dynamics of quantum waves is important, as the detection provides a way of understanding the quantum behavior of electrons in nano-electronics. It also applies to quantum information technologies such as the ultrafast quantum-bit operation of quantum computing and high-sensitivity electromagnetic-field sensing. However, detecting picosecond dynamics has been a challenge since the sub-terahertz scale is far beyond the latest bandwidth measurement tools.

A KAIST team led by Professor Heung-Sun Sim developed a theory of ultrafast electron dynamics in a nanoscale trap, and proposed a scheme for detecting the dynamics, which utilizes a quantum-mechanical resonant state formed beside the trap. The coupling between the electron dynamics and the resonant state is switched on and off at a picosecond so that information on the dynamics is read out on the electric current being generated when the coupling is switched on.

NTT realized, together with NPL, the detection scheme and applied it to electron motions in a nanoscale trap formed in a silicon transistor. A single electron was captured in the trap by controlling electrostatic gates, and a resonant state was formed in the potential barrier of the trap.

The switching on and off of the coupling between the electron and the resonant state was achieved by aligning the resonance energy with the energy of the electron within a picosecond. An electric current from the trap through the resonant state to an electrode was measured at only a few Kelvin degrees, unveiling the spatial quantum-coherent oscillation of the electron with 250 GHz frequency inside the trap.

Professor Sim said, “This work suggests a scheme of detecting picosecond electron motions in submicron scales by utilizing quantum resonance. It will be useful in dynamical control of quantum mechanical electron waves for various purposes in nano-electronics, quantum sensing, and quantum information”.

This work was published online at Nature Nanotechnology on November 4. It was partly supported by the Korea National Research Foundation through the SRC Center for Quantum Coherence in Condensed Matter. For more on the NTT news release this article, please visit https://www.ntt.co.jp/news2019/1911e/191105a.html

-ProfileProfessor Heung-Sun Sim

Department of PhysicsDirector, SRC Center for Quantum Coherence in Condensed Matterhttps://qet.kaist.ac.kr KAIST

-Publication:Gento Yamahata, Sungguen Ryu, Nathan Johnson, H.-S. Sim, Akira Fujiwara, and Masaya Kataoka. 2019. Picosecond coherent electron motion in a silicon single-electron source. Nature Nanotechnology (Online Publication). 6 pages. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41565-019-0563-2

2019.11.05 View 18471

Ultrafast Quantum Motion in a Nanoscale Trap Detected

< Professor Heung-Sun Sim (left) and Co-author Dr. Sungguen Ryu (right) >

KAIST researchers have reported the detection of a picosecond electron motion in a silicon transistor. This study has presented a new protocol for measuring ultrafast electronic dynamics in an effective time-resolved fashion of picosecond resolution. The detection was made in collaboration with Nippon Telegraph and Telephone Corp. (NTT) in Japan and National Physical Laboratory (NPL) in the UK and is the first report to the best of our knowledge.

When an electron is captured in a nanoscale trap in solids, its quantum mechanical wave function can exhibit spatial oscillation at sub-terahertz frequencies. Time-resolved detection of such picosecond dynamics of quantum waves is important, as the detection provides a way of understanding the quantum behavior of electrons in nano-electronics. It also applies to quantum information technologies such as the ultrafast quantum-bit operation of quantum computing and high-sensitivity electromagnetic-field sensing. However, detecting picosecond dynamics has been a challenge since the sub-terahertz scale is far beyond the latest bandwidth measurement tools.

A KAIST team led by Professor Heung-Sun Sim developed a theory of ultrafast electron dynamics in a nanoscale trap, and proposed a scheme for detecting the dynamics, which utilizes a quantum-mechanical resonant state formed beside the trap. The coupling between the electron dynamics and the resonant state is switched on and off at a picosecond so that information on the dynamics is read out on the electric current being generated when the coupling is switched on.

NTT realized, together with NPL, the detection scheme and applied it to electron motions in a nanoscale trap formed in a silicon transistor. A single electron was captured in the trap by controlling electrostatic gates, and a resonant state was formed in the potential barrier of the trap.

The switching on and off of the coupling between the electron and the resonant state was achieved by aligning the resonance energy with the energy of the electron within a picosecond. An electric current from the trap through the resonant state to an electrode was measured at only a few Kelvin degrees, unveiling the spatial quantum-coherent oscillation of the electron with 250 GHz frequency inside the trap.

Professor Sim said, “This work suggests a scheme of detecting picosecond electron motions in submicron scales by utilizing quantum resonance. It will be useful in dynamical control of quantum mechanical electron waves for various purposes in nano-electronics, quantum sensing, and quantum information”.

This work was published online at Nature Nanotechnology on November 4. It was partly supported by the Korea National Research Foundation through the SRC Center for Quantum Coherence in Condensed Matter. For more on the NTT news release this article, please visit https://www.ntt.co.jp/news2019/1911e/191105a.html

-ProfileProfessor Heung-Sun Sim

Department of PhysicsDirector, SRC Center for Quantum Coherence in Condensed Matterhttps://qet.kaist.ac.kr KAIST

-Publication:Gento Yamahata, Sungguen Ryu, Nathan Johnson, H.-S. Sim, Akira Fujiwara, and Masaya Kataoka. 2019. Picosecond coherent electron motion in a silicon single-electron source. Nature Nanotechnology (Online Publication). 6 pages. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41565-019-0563-2

2019.11.05 View 18471 -

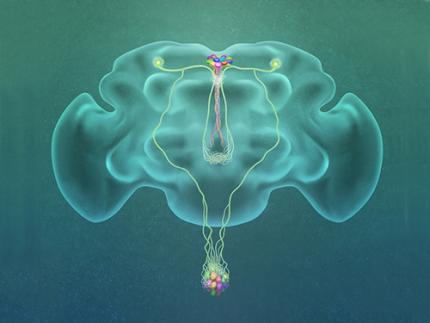

A Single, Master Switch for Sugar Levels?

When a fly eats sugar, a single brain cell sends simultaneous messages to stimulate one hormone and inhibit another to control glucose levels in the body. Further research into this control system with remarkable precision could shed light on the neural mechanisms of diabetes and obesity in humans .