research

-

Wirelessly Rechargeable Soft Brain Implant Controls Brain Cells

Researchers have invented a smartphone-controlled soft brain implant that can be recharged wirelessly from outside the body. It enables long-term neural circuit manipulation without the need for periodic disruptive surgeries to replace the battery of the implant. Scientists believe this technology can help uncover and treat psychiatric disorders and neurodegenerative diseases such as addiction, depression, and Parkinson’s.

A group of KAIST researchers and collaborators have engineered a tiny brain implant that can be wirelessly recharged from outside the body to control brain circuits for long periods of time without battery replacement. The device is constructed of ultra-soft and bio-compliant polymers to help provide long-term compatibility with tissue. Geared with micrometer-sized LEDs (equivalent to the size of a grain of salt) mounted on ultrathin probes (the thickness of a human hair), it can wirelessly manipulate target neurons in the deep brain using light.

This study, led by Professor Jae-Woong Jeong, is a step forward from the wireless head-mounted implant neural device he developed in 2019. That previous version could indefinitely deliver multiple drugs and light stimulation treatment wirelessly by using a smartphone. For more, Manipulating Brain Cells by Smartphone.

For the new upgraded version, the research team came up with a fully implantable, soft optoelectronic system that can be remotely and selectively controlled by a smartphone. This research was published on January 22, 2021 in Nature Communications.

The new wireless charging technology addresses the limitations of current brain implants. Wireless implantable device technologies have recently become popular as alternatives to conventional tethered implants, because they help minimize stress and inflammation in freely-moving animals during brain studies, which in turn enhance the lifetime of the devices. However, such devices require either intermittent surgeries to replace discharged batteries, or special and bulky wireless power setups, which limit experimental options as well as the scalability of animal experiments.

“This powerful device eliminates the need for additional painful surgeries to replace an exhausted battery in the implant, allowing seamless chronic neuromodulation,” said Professor Jeong. “We believe that the same basic technology can be applied to various types of implants, including deep brain stimulators, and cardiac and gastric pacemakers, to reduce the burden on patients for long-term use within the body.”

To enable wireless battery charging and controls, researchers developed a tiny circuit that integrates a wireless energy harvester with a coil antenna and a Bluetooth low-energy chip. An alternating magnetic field can harmlessly penetrate through tissue, and generate electricity inside the device to charge the battery. Then the battery-powered Bluetooth implant delivers programmable patterns of light to brain cells using an “easy-to-use” smartphone app for real-time brain control.

“This device can be operated anywhere and anytime to manipulate neural circuits, which makes it a highly versatile tool for investigating brain functions,” said lead author Choong Yeon Kim, a researcher at KAIST.

Neuroscientists successfully tested these implants in rats and demonstrated their ability to suppress cocaine-induced behaviour after the rats were injected with cocaine. This was achieved by precise light stimulation of relevant target neurons in their brains using the smartphone-controlled LEDs. Furthermore, the battery in the implants could be repeatedly recharged while the rats were behaving freely, thus minimizing any physical interruption to the experiments.

“Wireless battery re-charging makes experimental procedures much less complicated,” said the co-lead author Min Jeong Ku, a researcher at Yonsei University’s College of Medicine.

“The fact that we can control a specific behaviour of animals, by delivering light stimulation into the brain just with a simple manipulation of smartphone app, watching freely moving animals nearby, is very interesting and stimulates a lot of imagination,” said Jeong-Hoon Kim, a professor of physiology at Yonsei University’s College of Medicine. “This technology will facilitate various avenues of brain research.”

The researchers believe this brain implant technology may lead to new opportunities for brain research and therapeutic intervention to treat diseases in the brain and other organs.

This work was supported by grants from the National Research Foundation of Korea and the KAIST Global Singularity Research Program.

-Profile

Professor Jae-Woong Jeong

https://www.jeongresearch.org/

School of Electrical Engineering

KAIST

2021.01.26 View 26193

Wirelessly Rechargeable Soft Brain Implant Controls Brain Cells

Researchers have invented a smartphone-controlled soft brain implant that can be recharged wirelessly from outside the body. It enables long-term neural circuit manipulation without the need for periodic disruptive surgeries to replace the battery of the implant. Scientists believe this technology can help uncover and treat psychiatric disorders and neurodegenerative diseases such as addiction, depression, and Parkinson’s.

A group of KAIST researchers and collaborators have engineered a tiny brain implant that can be wirelessly recharged from outside the body to control brain circuits for long periods of time without battery replacement. The device is constructed of ultra-soft and bio-compliant polymers to help provide long-term compatibility with tissue. Geared with micrometer-sized LEDs (equivalent to the size of a grain of salt) mounted on ultrathin probes (the thickness of a human hair), it can wirelessly manipulate target neurons in the deep brain using light.

This study, led by Professor Jae-Woong Jeong, is a step forward from the wireless head-mounted implant neural device he developed in 2019. That previous version could indefinitely deliver multiple drugs and light stimulation treatment wirelessly by using a smartphone. For more, Manipulating Brain Cells by Smartphone.

For the new upgraded version, the research team came up with a fully implantable, soft optoelectronic system that can be remotely and selectively controlled by a smartphone. This research was published on January 22, 2021 in Nature Communications.

The new wireless charging technology addresses the limitations of current brain implants. Wireless implantable device technologies have recently become popular as alternatives to conventional tethered implants, because they help minimize stress and inflammation in freely-moving animals during brain studies, which in turn enhance the lifetime of the devices. However, such devices require either intermittent surgeries to replace discharged batteries, or special and bulky wireless power setups, which limit experimental options as well as the scalability of animal experiments.

“This powerful device eliminates the need for additional painful surgeries to replace an exhausted battery in the implant, allowing seamless chronic neuromodulation,” said Professor Jeong. “We believe that the same basic technology can be applied to various types of implants, including deep brain stimulators, and cardiac and gastric pacemakers, to reduce the burden on patients for long-term use within the body.”

To enable wireless battery charging and controls, researchers developed a tiny circuit that integrates a wireless energy harvester with a coil antenna and a Bluetooth low-energy chip. An alternating magnetic field can harmlessly penetrate through tissue, and generate electricity inside the device to charge the battery. Then the battery-powered Bluetooth implant delivers programmable patterns of light to brain cells using an “easy-to-use” smartphone app for real-time brain control.

“This device can be operated anywhere and anytime to manipulate neural circuits, which makes it a highly versatile tool for investigating brain functions,” said lead author Choong Yeon Kim, a researcher at KAIST.

Neuroscientists successfully tested these implants in rats and demonstrated their ability to suppress cocaine-induced behaviour after the rats were injected with cocaine. This was achieved by precise light stimulation of relevant target neurons in their brains using the smartphone-controlled LEDs. Furthermore, the battery in the implants could be repeatedly recharged while the rats were behaving freely, thus minimizing any physical interruption to the experiments.

“Wireless battery re-charging makes experimental procedures much less complicated,” said the co-lead author Min Jeong Ku, a researcher at Yonsei University’s College of Medicine.

“The fact that we can control a specific behaviour of animals, by delivering light stimulation into the brain just with a simple manipulation of smartphone app, watching freely moving animals nearby, is very interesting and stimulates a lot of imagination,” said Jeong-Hoon Kim, a professor of physiology at Yonsei University’s College of Medicine. “This technology will facilitate various avenues of brain research.”

The researchers believe this brain implant technology may lead to new opportunities for brain research and therapeutic intervention to treat diseases in the brain and other organs.

This work was supported by grants from the National Research Foundation of Korea and the KAIST Global Singularity Research Program.

-Profile

Professor Jae-Woong Jeong

https://www.jeongresearch.org/

School of Electrical Engineering

KAIST

2021.01.26 View 26193 -

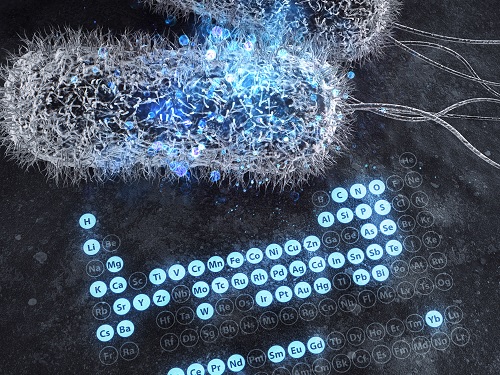

Expanding the Biosynthetic Pathway via Retrobiosynthesis

- Researchers reports a new strategy for the microbial production of multiple short-chain primary amines via retrobiosynthesis. -

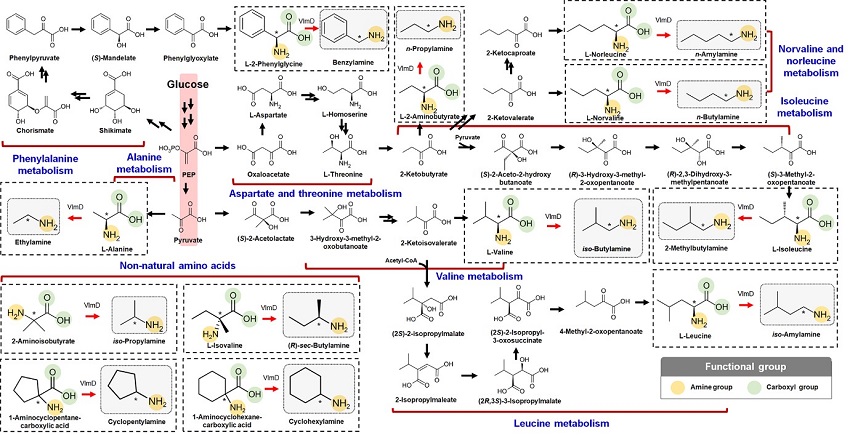

KAIST metabolic engineers presented the bio-based production of multiple short-chain primary amines that have a wide range of applications in chemical industries for the first time. The research team led by Distinguished Professor Sang Yup Lee from the Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering designed the novel biosynthetic pathways for short-chain primary amines by combining retrobiosynthesis and a precursor selection step.

The research team verified the newly designed pathways by confirming the in vivo production of 10 short-chain primary amines by supplying the precursors. Furthermore, the platform Escherichia coli strains were metabolically engineered to produce three proof-of-concept short-chain primary amines from glucose, demonstrating the possibility of the bio-based production of diverse short-chain primary amines from renewable resources. The research team said this study expands the strategy of systematically designing biosynthetic pathways for the production of a group of related chemicals as demonstrated by multiple short-chain primary amines as examples.

Currently, most of the industrial chemicals used in our daily lives are produced with petroleum-based products. However, there are several serious issues with the petroleum industry such as the depletion of fossil fuel reserves and environmental problems including global warming. To solve these problems, the sustainable production of industrial chemicals and materials is being explored with microorganisms as cell factories and renewable non-food biomass as raw materials for alternative to petroleum-based products. The engineering of these microorganisms has increasingly become more efficient and effective with the help of systems metabolic engineering – a practice of engineering the metabolism of a living organism toward the production of a desired metabolite. In this regard, the number of chemicals produced using biomass as a raw material has substantially increased.

Although the scope of chemicals that are producible using microorganisms continues to expand through advances in systems metabolic engineering, the biological production of short-chain primary amines has not yet been reported despite their industrial importance. Short-chain primary amines are the chemicals that have an alkyl or aryl group in the place of a hydrogen atom in ammonia with carbon chain lengths ranging from C1 to C7. Short-chain primary amines have a wide range of applications in chemical industries, for example, as a precursor for pharmaceuticals (e.g., antidiabetic and antihypertensive drugs), agrochemicals (e.g., herbicides, fungicides and insecticides), solvents, and vulcanization accelerators for rubber and plasticizers. The market size of short-chain primary amines was estimated to be more than 4 billion US dollars in 2014.

The main reason why the bio-based production of short-chain primary amines was not yet possible was due to their unknown biosynthetic pathways. Therefore, the team designed synthetic biosynthetic pathways for short-chain primary amines by combining retrobiosynthesis and a precursor selection step. The retrobiosynthesis allowed the systematic design of a biosynthetic pathway for short-chain primary amines by using a set of biochemical reaction rules that describe chemical transformation patterns between a substrate and product molecules at an atomic level.

These multiple precursors predicted for the possible biosynthesis of each short-chain primary amine were sequentially narrowed down by using the precursor selection step for efficient metabolic engineering experiments.

“Our research demonstrates the possibility of the renewable production of short-chain primary amines for the first time. We are planning to increase production efficiencies of short-chain primary amines. We believe that our study will play an important role in the development of sustainable and eco-friendly bio-based industries and the reorganization of the chemical industry, which is mandatory for solving the environmental problems threating the survival of mankind,” said Professor Lee.

This paper titled “Microbial production of multiple short-chain primary amines via retrobiosynthesis” was published in Nature Communications. This work was supported by the Technology Development Program to Solve Climate Changes on Systems Metabolic Engineering for Biorefineries from the Ministry of Science and ICT through the National Research Foundation (NRF) of Korea.

-Publication

Dong In Kim, Tong Un Chae, Hyun Uk Kim, Woo Dae Jang, and Sang Yup Lee. Microbial production of multiple short-chain primary amines via retrobiosynthesis. Nature Communications ( https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-020-20423-6)

-Profile

Distinguished Professor Sang Yup Lee

leesy@kaist.ac.kr

Metabolic &Biomolecular Engineering National Research Laboratory

http://mbel.kaist.ac.kr

Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering

KAIST

2021.01.14 View 12429

Expanding the Biosynthetic Pathway via Retrobiosynthesis

- Researchers reports a new strategy for the microbial production of multiple short-chain primary amines via retrobiosynthesis. -

KAIST metabolic engineers presented the bio-based production of multiple short-chain primary amines that have a wide range of applications in chemical industries for the first time. The research team led by Distinguished Professor Sang Yup Lee from the Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering designed the novel biosynthetic pathways for short-chain primary amines by combining retrobiosynthesis and a precursor selection step.

The research team verified the newly designed pathways by confirming the in vivo production of 10 short-chain primary amines by supplying the precursors. Furthermore, the platform Escherichia coli strains were metabolically engineered to produce three proof-of-concept short-chain primary amines from glucose, demonstrating the possibility of the bio-based production of diverse short-chain primary amines from renewable resources. The research team said this study expands the strategy of systematically designing biosynthetic pathways for the production of a group of related chemicals as demonstrated by multiple short-chain primary amines as examples.

Currently, most of the industrial chemicals used in our daily lives are produced with petroleum-based products. However, there are several serious issues with the petroleum industry such as the depletion of fossil fuel reserves and environmental problems including global warming. To solve these problems, the sustainable production of industrial chemicals and materials is being explored with microorganisms as cell factories and renewable non-food biomass as raw materials for alternative to petroleum-based products. The engineering of these microorganisms has increasingly become more efficient and effective with the help of systems metabolic engineering – a practice of engineering the metabolism of a living organism toward the production of a desired metabolite. In this regard, the number of chemicals produced using biomass as a raw material has substantially increased.

Although the scope of chemicals that are producible using microorganisms continues to expand through advances in systems metabolic engineering, the biological production of short-chain primary amines has not yet been reported despite their industrial importance. Short-chain primary amines are the chemicals that have an alkyl or aryl group in the place of a hydrogen atom in ammonia with carbon chain lengths ranging from C1 to C7. Short-chain primary amines have a wide range of applications in chemical industries, for example, as a precursor for pharmaceuticals (e.g., antidiabetic and antihypertensive drugs), agrochemicals (e.g., herbicides, fungicides and insecticides), solvents, and vulcanization accelerators for rubber and plasticizers. The market size of short-chain primary amines was estimated to be more than 4 billion US dollars in 2014.

The main reason why the bio-based production of short-chain primary amines was not yet possible was due to their unknown biosynthetic pathways. Therefore, the team designed synthetic biosynthetic pathways for short-chain primary amines by combining retrobiosynthesis and a precursor selection step. The retrobiosynthesis allowed the systematic design of a biosynthetic pathway for short-chain primary amines by using a set of biochemical reaction rules that describe chemical transformation patterns between a substrate and product molecules at an atomic level.

These multiple precursors predicted for the possible biosynthesis of each short-chain primary amine were sequentially narrowed down by using the precursor selection step for efficient metabolic engineering experiments.

“Our research demonstrates the possibility of the renewable production of short-chain primary amines for the first time. We are planning to increase production efficiencies of short-chain primary amines. We believe that our study will play an important role in the development of sustainable and eco-friendly bio-based industries and the reorganization of the chemical industry, which is mandatory for solving the environmental problems threating the survival of mankind,” said Professor Lee.

This paper titled “Microbial production of multiple short-chain primary amines via retrobiosynthesis” was published in Nature Communications. This work was supported by the Technology Development Program to Solve Climate Changes on Systems Metabolic Engineering for Biorefineries from the Ministry of Science and ICT through the National Research Foundation (NRF) of Korea.

-Publication

Dong In Kim, Tong Un Chae, Hyun Uk Kim, Woo Dae Jang, and Sang Yup Lee. Microbial production of multiple short-chain primary amines via retrobiosynthesis. Nature Communications ( https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-020-20423-6)

-Profile

Distinguished Professor Sang Yup Lee

leesy@kaist.ac.kr

Metabolic &Biomolecular Engineering National Research Laboratory

http://mbel.kaist.ac.kr

Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering

KAIST

2021.01.14 View 12429 -

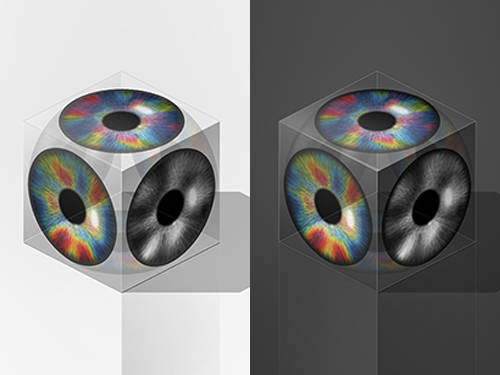

A Biological Strategy Reveals How Efficient Brain Circuitry Develops Spontaneously

- A KAIST team’s mathematical modelling shows that the topographic tiling of cortical maps originates from bottom-up projections from the periphery. -

Researchers have explained how the regularly structured topographic maps in the visual cortex of the brain could arise spontaneously to efficiently process visual information. This research provides a new framework for understanding functional architectures in the visual cortex during early developmental stages.

A KAIST research team led by Professor Se-Bum Paik from the Department of Bio and Brain Engineering has demonstrated that the orthogonal organization of retinal mosaics in the periphery is mirrored onto the primary visual cortex and initiates the clustered topography of higher visual areas in the brain.

This new finding provides advanced insights into the mechanisms underlying a biological strategy of brain circuitry for the efficient tiling of sensory modules. The study was published in Cell Reports on January 5.

In higher mammals, the primary visual cortex is organized into various functional maps for neural tuning such as ocular dominance, orientation selectivity, and spatial frequency selectivity. Correlations between the topographies of different maps have been observed, implying their systematic organizations for the efficient tiling of sensory modules across cortical areas.

These observations have suggested that a common principle for developing individual functional maps may exist. However, it has remained unclear how such topographical organizations could arise spontaneously in the primary visual cortex of various species.

The research team found that the orthogonal organization in the primary visual cortex of the brain originates from the spatial organization in bottom-up feedforward projections. The team showed that an orthogonal relationship among sensory modules already exists in the retinal mosaics, and that this is mirrored onto the primary visual cortex to initiate the clustered topography.

By analyzing the retinal ganglion cell mosaics data in cats and monkeys, the researchers found that the structure of ON-OFF feedforward afferents is organized into a topographic tiling, analogous to the orthogonal intersection of cortical tuning maps.

Furthermore, the team’s analysis of previously published data collected on cats also showed that the ocular dominance, orientation selectivity, and spatial frequency selectivity in the primary visual cortex are correlated with the spatial profiles of the retinal inputs, implying that efficient tiling of cortical domains can originate from the regularly structured retinal patterns.

Professor Paik said, “Our study suggests that the structure of the periphery with simple feedforward wiring can provide the basis for a mechanism by which the early visual circuitry is assembled.”

He continued, “This is the first report that spatially organized retinal inputs from the periphery provide a common blueprint for multi-modal sensory modules in the visual cortex during the early developmental stages. Our findings would make a significant impact on our understanding the developmental strategy of brain circuitry for efficient sensory information processing.”

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF).

Image credit: Professor Se-Bum Paik, KAIST

Image usage restrictions: News organizations may use or redistribute this image, with proper attribution, as part of news coverage of this paper only.

Publication:

Song, M, et al. (2021) Projection of orthogonal tiling from the retina to the visual cortex. Cell Reports 34, 108581. Available online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108581

Profile:

Se-Bum Paik, Ph.D

Assistant Professor

sbpaik@kaist.ac.kr

http://vs.kaist.ac.kr/

VSNN Laboratory

Department of Bio and Brain Engineering

Program of Brain and Cognitive Engineering

http://kaist.ac.kr

Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST) Daejeon, Republic of Korea

Profile:

Min Song

Ph.D. Candidate

night@kaist.ac.kr

Program of Brain and Cognitive Engineering

Profile:

Jaeson Jang, Ph.D.

Researcher

jaesonjang@kaist.ac.kr

Department of Bio and Brain Engineering, KAIST

(END)

2021.01.14 View 8168

A Biological Strategy Reveals How Efficient Brain Circuitry Develops Spontaneously

- A KAIST team’s mathematical modelling shows that the topographic tiling of cortical maps originates from bottom-up projections from the periphery. -

Researchers have explained how the regularly structured topographic maps in the visual cortex of the brain could arise spontaneously to efficiently process visual information. This research provides a new framework for understanding functional architectures in the visual cortex during early developmental stages.

A KAIST research team led by Professor Se-Bum Paik from the Department of Bio and Brain Engineering has demonstrated that the orthogonal organization of retinal mosaics in the periphery is mirrored onto the primary visual cortex and initiates the clustered topography of higher visual areas in the brain.

This new finding provides advanced insights into the mechanisms underlying a biological strategy of brain circuitry for the efficient tiling of sensory modules. The study was published in Cell Reports on January 5.

In higher mammals, the primary visual cortex is organized into various functional maps for neural tuning such as ocular dominance, orientation selectivity, and spatial frequency selectivity. Correlations between the topographies of different maps have been observed, implying their systematic organizations for the efficient tiling of sensory modules across cortical areas.

These observations have suggested that a common principle for developing individual functional maps may exist. However, it has remained unclear how such topographical organizations could arise spontaneously in the primary visual cortex of various species.

The research team found that the orthogonal organization in the primary visual cortex of the brain originates from the spatial organization in bottom-up feedforward projections. The team showed that an orthogonal relationship among sensory modules already exists in the retinal mosaics, and that this is mirrored onto the primary visual cortex to initiate the clustered topography.

By analyzing the retinal ganglion cell mosaics data in cats and monkeys, the researchers found that the structure of ON-OFF feedforward afferents is organized into a topographic tiling, analogous to the orthogonal intersection of cortical tuning maps.

Furthermore, the team’s analysis of previously published data collected on cats also showed that the ocular dominance, orientation selectivity, and spatial frequency selectivity in the primary visual cortex are correlated with the spatial profiles of the retinal inputs, implying that efficient tiling of cortical domains can originate from the regularly structured retinal patterns.

Professor Paik said, “Our study suggests that the structure of the periphery with simple feedforward wiring can provide the basis for a mechanism by which the early visual circuitry is assembled.”

He continued, “This is the first report that spatially organized retinal inputs from the periphery provide a common blueprint for multi-modal sensory modules in the visual cortex during the early developmental stages. Our findings would make a significant impact on our understanding the developmental strategy of brain circuitry for efficient sensory information processing.”

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF).

Image credit: Professor Se-Bum Paik, KAIST

Image usage restrictions: News organizations may use or redistribute this image, with proper attribution, as part of news coverage of this paper only.

Publication:

Song, M, et al. (2021) Projection of orthogonal tiling from the retina to the visual cortex. Cell Reports 34, 108581. Available online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108581

Profile:

Se-Bum Paik, Ph.D

Assistant Professor

sbpaik@kaist.ac.kr

http://vs.kaist.ac.kr/

VSNN Laboratory

Department of Bio and Brain Engineering

Program of Brain and Cognitive Engineering

http://kaist.ac.kr

Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST) Daejeon, Republic of Korea

Profile:

Min Song

Ph.D. Candidate

night@kaist.ac.kr

Program of Brain and Cognitive Engineering

Profile:

Jaeson Jang, Ph.D.

Researcher

jaesonjang@kaist.ac.kr

Department of Bio and Brain Engineering, KAIST

(END)

2021.01.14 View 8168 -

KAIST Mobile Clinic Module to Fill Negative Pressure Ward Shortage

Efficient versatile ready-for-rapid building system of MCM will serve as both a triage unit and bridge center in emergency medical situations

A team from KAIST has developed a low-cost and ready-for-rapid-production negative pressure room called a Mobile Clinic Module (MCM). The MCM is expandable, moveable, and easy to store through a combination of negative pressure frames, air tents, and multi-function panels.

The MCM expects to quickly meet the high demand for negative pressure beds in the nation and eventually many other countries where the third wave of COVID-19 is raging. The module is now ready to be rolled out after a three-week test period at the Korea Cancer Center Hospital.

Professor Tek-Jin Nam’s team swung into action, rapidly working together with researchers, engineers with expertise in mechanical design, and a team of clinical doctors to complete the MCM as one of KAIST’s New Deal R&D initiatives launched last July.

Professor Nam cites ‘expandability’ as the key feature of the MCM. Eventually, it will serve as both a triage unit and bridge center in emergency medical situations.

“The module is a very efficient and versatile unit building system. It takes approximately two hours to build the basic MCM unit, which comprises four negative pressure bed rooms, nurse’s station, locker room, and treatment room. We believe this will significantly contribute to relieving the drastic need for negative pressure beds and provide a place for monitoring patients with moderate symptoms,” said Professor Nam.

“It will also be helpful for managing less-severe patients who need to be monitored daily in quarantined rooms or as bridge stations where on-site medical staff can provide treatment and daily monitoring before hospitalization. These wards can be efficiently deployed either inside or outside existing hospitals.”

The research team specially designed the negative pressure frame to ensure safety level A for the negative pressure room, which is made of a multi-function panel wall and roofed with an air tent. The multi-function panels can hold medical appliances such as ventilators, oxygen and bio-signal monitors.

Positive air pressure devices supply fresh air from outside the tent. An air pump and controller maintain air beam pressure, while filtering exhausted air. An internal air information monitoring system efficiently controls room air pressure and purifies the air.

While a conventional negative pressure bed is reported to cost approximately 3.5 billion KRW (50 billion won for a ward), this module is estimated to cost 0.75 billion won each (10 billion won for a ward), cutting the costs by approximately 80%.

The MCM is designed to be easily transported and relocated due to its volume, weight, and maintainability. This module requires only one-fourth of the volume of existing wards and takes up approximately 40% of their weight. The unit can be transported in a 40-foot container truck.

“We believe this will significantly contribute to relieving the drastic need for negative pressure beds and provide a place for monitoring patients with moderate symptoms. We look forward to the MCM upgrading epidemic management resources around the world.”

Professor Nam’s team is also developing antiviral solutions and devices such as protective gear, sterilizers, and test kits under the KAIST New Deal R&D Initiative that was launched to promptly and proactively respond to the epidemic. More than 45 faculty members and researchers at KAIST are collaborating with industry and clinical hospitals to develop the antiviral technology that will improve preventive measures, diagnoses, and treatment.

2021.01.07 View 12212

KAIST Mobile Clinic Module to Fill Negative Pressure Ward Shortage

Efficient versatile ready-for-rapid building system of MCM will serve as both a triage unit and bridge center in emergency medical situations

A team from KAIST has developed a low-cost and ready-for-rapid-production negative pressure room called a Mobile Clinic Module (MCM). The MCM is expandable, moveable, and easy to store through a combination of negative pressure frames, air tents, and multi-function panels.

The MCM expects to quickly meet the high demand for negative pressure beds in the nation and eventually many other countries where the third wave of COVID-19 is raging. The module is now ready to be rolled out after a three-week test period at the Korea Cancer Center Hospital.

Professor Tek-Jin Nam’s team swung into action, rapidly working together with researchers, engineers with expertise in mechanical design, and a team of clinical doctors to complete the MCM as one of KAIST’s New Deal R&D initiatives launched last July.

Professor Nam cites ‘expandability’ as the key feature of the MCM. Eventually, it will serve as both a triage unit and bridge center in emergency medical situations.

“The module is a very efficient and versatile unit building system. It takes approximately two hours to build the basic MCM unit, which comprises four negative pressure bed rooms, nurse’s station, locker room, and treatment room. We believe this will significantly contribute to relieving the drastic need for negative pressure beds and provide a place for monitoring patients with moderate symptoms,” said Professor Nam.

“It will also be helpful for managing less-severe patients who need to be monitored daily in quarantined rooms or as bridge stations where on-site medical staff can provide treatment and daily monitoring before hospitalization. These wards can be efficiently deployed either inside or outside existing hospitals.”

The research team specially designed the negative pressure frame to ensure safety level A for the negative pressure room, which is made of a multi-function panel wall and roofed with an air tent. The multi-function panels can hold medical appliances such as ventilators, oxygen and bio-signal monitors.

Positive air pressure devices supply fresh air from outside the tent. An air pump and controller maintain air beam pressure, while filtering exhausted air. An internal air information monitoring system efficiently controls room air pressure and purifies the air.

While a conventional negative pressure bed is reported to cost approximately 3.5 billion KRW (50 billion won for a ward), this module is estimated to cost 0.75 billion won each (10 billion won for a ward), cutting the costs by approximately 80%.

The MCM is designed to be easily transported and relocated due to its volume, weight, and maintainability. This module requires only one-fourth of the volume of existing wards and takes up approximately 40% of their weight. The unit can be transported in a 40-foot container truck.

“We believe this will significantly contribute to relieving the drastic need for negative pressure beds and provide a place for monitoring patients with moderate symptoms. We look forward to the MCM upgrading epidemic management resources around the world.”

Professor Nam’s team is also developing antiviral solutions and devices such as protective gear, sterilizers, and test kits under the KAIST New Deal R&D Initiative that was launched to promptly and proactively respond to the epidemic. More than 45 faculty members and researchers at KAIST are collaborating with industry and clinical hospitals to develop the antiviral technology that will improve preventive measures, diagnoses, and treatment.

2021.01.07 View 12212 -

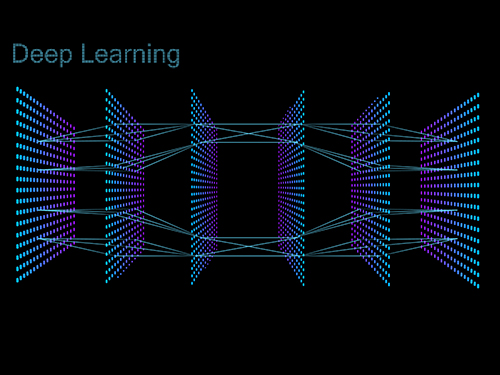

DeepTFactor Predicts Transcription Factors

A deep learning-based tool predicts transcription factors using protein sequences as inputs

A joint research team from KAIST and UCSD has developed a deep neural network named DeepTFactor that predicts transcription factors from protein sequences. DeepTFactor will serve as a useful tool for understanding the regulatory systems of organisms, accelerating the use of deep learning for solving biological problems.

A transcription factor is a protein that specifically binds to DNA sequences to control the transcription initiation. Analyzing transcriptional regulation enables the understanding of how organisms control gene expression in response to genetic or environmental changes. In this regard, finding the transcription factor of an organism is the first step in the analysis of the transcriptional regulatory system of an organism.

Previously, transcription factors have been predicted by analyzing sequence homology with already characterized transcription factors or by data-driven approaches such as machine learning. Conventional machine learning models require a rigorous feature selection process that relies on domain expertise such as calculating the physicochemical properties of molecules or analyzing the homology of biological sequences. Meanwhile, deep learning can inherently learn latent features for the specific task.

A joint research team comprised of Ph.D. candidate Gi Bae Kim and Distinguished Professor Sang Yup Lee of the Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering at KAIST, and Ye Gao and Professor Bernhard O. Palsson of the Department of Biochemical Engineering at UCSD reported a deep learning-based tool for the prediction of transcription factors. Their research paper “DeepTFactor: A deep learning-based tool for the prediction of transcription factors” was published online in PNAS.

Their article reports the development of DeepTFactor, a deep learning-based tool that predicts whether a given protein sequence is a transcription factor using three parallel convolutional neural networks. The joint research team predicted 332 transcription factors of Escherichia coli K-12 MG1655 using DeepTFactor and the performance of DeepTFactor by experimentally confirming the genome-wide binding sites of three predicted transcription factors (YqhC, YiaU, and YahB).

The joint research team further used a saliency method to understand the reasoning process of DeepTFactor. The researchers confirmed that even though information on the DNA binding domains of the transcription factor was not explicitly given the training process, DeepTFactor implicitly learned and used them for prediction. Unlike previous transcription factor prediction tools that were developed only for protein sequences of specific organisms, DeepTFactor is expected to be used in the analysis of the transcription systems of all organisms at a high level of performance.

Distinguished Professor Sang Yup Lee said, “DeepTFactor can be used to discover unknown transcription factors from numerous protein sequences that have not yet been characterized. It is expected that DeepTFactor will serve as an important tool for analyzing the regulatory systems of organisms of interest.”

This work was supported by the Technology Development Program to Solve Climate Changes on Systems Metabolic Engineering for Biorefineries from the Ministry of Science and ICT through the National Research Foundation of Korea.

-Publication

Gi Bae Kim, Ye Gao, Bernhard O. Palsson, and Sang Yup Lee. DeepTFactor: A deep learning-based tool for the prediction of transcription factors. (https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas202117118)

-Profile

Distinguished Professor Sang Yup Lee

leesy@kaist.ac.kr

Metabolic &Biomolecular Engineering National Research Laboratory

http://mbel.kaist.ac.kr

Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering

KAIST

2021.01.05 View 9860

DeepTFactor Predicts Transcription Factors

A deep learning-based tool predicts transcription factors using protein sequences as inputs

A joint research team from KAIST and UCSD has developed a deep neural network named DeepTFactor that predicts transcription factors from protein sequences. DeepTFactor will serve as a useful tool for understanding the regulatory systems of organisms, accelerating the use of deep learning for solving biological problems.

A transcription factor is a protein that specifically binds to DNA sequences to control the transcription initiation. Analyzing transcriptional regulation enables the understanding of how organisms control gene expression in response to genetic or environmental changes. In this regard, finding the transcription factor of an organism is the first step in the analysis of the transcriptional regulatory system of an organism.

Previously, transcription factors have been predicted by analyzing sequence homology with already characterized transcription factors or by data-driven approaches such as machine learning. Conventional machine learning models require a rigorous feature selection process that relies on domain expertise such as calculating the physicochemical properties of molecules or analyzing the homology of biological sequences. Meanwhile, deep learning can inherently learn latent features for the specific task.

A joint research team comprised of Ph.D. candidate Gi Bae Kim and Distinguished Professor Sang Yup Lee of the Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering at KAIST, and Ye Gao and Professor Bernhard O. Palsson of the Department of Biochemical Engineering at UCSD reported a deep learning-based tool for the prediction of transcription factors. Their research paper “DeepTFactor: A deep learning-based tool for the prediction of transcription factors” was published online in PNAS.

Their article reports the development of DeepTFactor, a deep learning-based tool that predicts whether a given protein sequence is a transcription factor using three parallel convolutional neural networks. The joint research team predicted 332 transcription factors of Escherichia coli K-12 MG1655 using DeepTFactor and the performance of DeepTFactor by experimentally confirming the genome-wide binding sites of three predicted transcription factors (YqhC, YiaU, and YahB).

The joint research team further used a saliency method to understand the reasoning process of DeepTFactor. The researchers confirmed that even though information on the DNA binding domains of the transcription factor was not explicitly given the training process, DeepTFactor implicitly learned and used them for prediction. Unlike previous transcription factor prediction tools that were developed only for protein sequences of specific organisms, DeepTFactor is expected to be used in the analysis of the transcription systems of all organisms at a high level of performance.

Distinguished Professor Sang Yup Lee said, “DeepTFactor can be used to discover unknown transcription factors from numerous protein sequences that have not yet been characterized. It is expected that DeepTFactor will serve as an important tool for analyzing the regulatory systems of organisms of interest.”

This work was supported by the Technology Development Program to Solve Climate Changes on Systems Metabolic Engineering for Biorefineries from the Ministry of Science and ICT through the National Research Foundation of Korea.

-Publication

Gi Bae Kim, Ye Gao, Bernhard O. Palsson, and Sang Yup Lee. DeepTFactor: A deep learning-based tool for the prediction of transcription factors. (https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas202117118)

-Profile

Distinguished Professor Sang Yup Lee

leesy@kaist.ac.kr

Metabolic &Biomolecular Engineering National Research Laboratory

http://mbel.kaist.ac.kr

Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering

KAIST

2021.01.05 View 9860 -

Extremely Stable Perovskite Nanoparticles Films for Next-Generation Displays

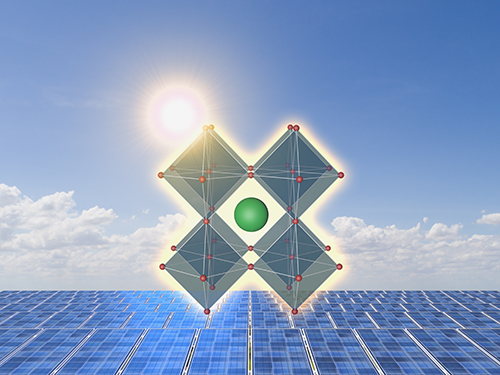

Researchers have reported an extremely stable cross-linked perovskite nanoparticle that maintains a high photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) for 1.5 years in air and harsh liquid environments. This stable material’s design strategies, which addressed one of the most critical problems limiting their practical application, provide a breakthrough for the commercialization of perovskite nanoparticles in next-generation displays and bio-related applications.

According to the research team led by Professor Byeong-Soo Bae, their development can survive in severe environments such as water, various polar solvents, and high temperature with high humidity without additional encapsulation. This development is expected to enable perovskite nanoparticles to be applied to high color purity display applications as a practical color converting material. This result was published as the inside front cover article in Advanced Materials.

Perovskites, which consist of organics, metals, and halogen elements, have emerged as key elements in various optoelectronic applications. The power conversion efficiency of photovoltaic cells based on perovskites light absorbers has been rapidly increased. Perovskites are also great promise as a light emitter in display applications because of their low material cost, facile wavelength tunability, high (PLQY), very narrow emission band width, and wider color gamut than inorganic semiconducting nanocrystals and organic emitters. Thanks to these advantages, perovskites have been identified as a key color-converting material for next-generation high color-purity displays. In particular, perovskites are the only luminescence material that meets Rec. 2020 which is a new color standard in display industry.

However, perovskites are very unstable against heat, moisture, and light, which makes them almost impossible to use in practical applications. To solve these problems, many researchers have attempted to physically prevent perovskites from coming into contact with water molecules by passivating the perovskite grain and nanoparticle surfaces with organic ligands or inorganic shell materials, or by fabricating perovskite-polymer nanocomposites. These methods require complex processes and have limited stability in ambient air and water. Furthermore, stable perovskite nanoparticles in the various chemical environments and high temperatures with high humidity have not been reported yet.

The research team in collaboration with Seoul National University develops siloxane-encapsulated perovskite nanoparticle composite films. Here, perovskite nanoparticles are chemically crosslinked with thermally stable siloxane molecules, thereby significantly improving the stability of the perovskite nanoparticles without the need for any additional protecting layer.

Siloxane-encapsulated perovskite nanoparticle composite films exhibited a high PLQY (> 70%) value, which can be maintained over 600 days in water, various chemicals (alcohol, strong acidic and basic solutions), and high temperatures with high humidity (85℃/85%). The research team investigated the mechanisms impacting the chemical crosslinking and water molecule-induced stabilization of perovskite nanoparticles through various photo-physical analysis and density-functional theory calculation.

The research team confirmed that displays based on their siloxane-perovskite nanoparticle composite films exhibited higher PLQY and a wider color gamut than those of Cd-based quantum dots and demonstrated perfect color converting properties on commercial mobile phone screens. Unlike what was commonly believed in the halide perovskite field, the composite films showed excellent bio-compatibility because the siloxane matrix prevents the toxicity of Pb in perovskite nanoparticle.

By using this technology, the instability of perovskite materials, which is the biggest challenge for practical applications, is greatly improved through simple encapsulation method.

“Perovskite nanoparticle is the only photoluminescent material that can meet the next generation display color standard. Nevertheless, there has been reluctant to commercialize it due to its moisture vulnerability. The newly developed siloxane encapsulation technology will trigger more research on perovskite nanoparticles as color conversion materials and will accelerate early commercialization,” Professor Bae said.

This work was supported by the Wearable Platform Materials Technology Center (WMC) of the Engineering Research Center (ERC) Project, and the Leadership Research Program funded by the National Research Foundation of Korea.

-Publication:

Junho Jang, Young-Hoon Kim, Sunjoon Park, Dongsuk Yoo, Hyunjin Cho, Jinhyeong Jang, Han Beom Jeong, Hyunhwan Lee, Jong Min Yuk, Chan Beum Park, Duk Young Jeon, Yong-Hyun Kim, Byeong-Soo Bae, and Tae-Woo Lee. “Extremely Stable Luminescent Crosslinked Perovskite Nanoparticles under Harsh Environments over 1.5 Years” Advanced Materials, 2020, 2005255. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202005255.

Link to download the full-text paper:

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/adma.202005255

-Profile: Prof. Byeong-Soo Bae (Corresponding author)

bsbae@kaist.ac.kr

Lab. of Optical Materials & Coating

Department of Materials Science and Engineering

Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST)

2020.12.29 View 13683

Extremely Stable Perovskite Nanoparticles Films for Next-Generation Displays

Researchers have reported an extremely stable cross-linked perovskite nanoparticle that maintains a high photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) for 1.5 years in air and harsh liquid environments. This stable material’s design strategies, which addressed one of the most critical problems limiting their practical application, provide a breakthrough for the commercialization of perovskite nanoparticles in next-generation displays and bio-related applications.

According to the research team led by Professor Byeong-Soo Bae, their development can survive in severe environments such as water, various polar solvents, and high temperature with high humidity without additional encapsulation. This development is expected to enable perovskite nanoparticles to be applied to high color purity display applications as a practical color converting material. This result was published as the inside front cover article in Advanced Materials.

Perovskites, which consist of organics, metals, and halogen elements, have emerged as key elements in various optoelectronic applications. The power conversion efficiency of photovoltaic cells based on perovskites light absorbers has been rapidly increased. Perovskites are also great promise as a light emitter in display applications because of their low material cost, facile wavelength tunability, high (PLQY), very narrow emission band width, and wider color gamut than inorganic semiconducting nanocrystals and organic emitters. Thanks to these advantages, perovskites have been identified as a key color-converting material for next-generation high color-purity displays. In particular, perovskites are the only luminescence material that meets Rec. 2020 which is a new color standard in display industry.

However, perovskites are very unstable against heat, moisture, and light, which makes them almost impossible to use in practical applications. To solve these problems, many researchers have attempted to physically prevent perovskites from coming into contact with water molecules by passivating the perovskite grain and nanoparticle surfaces with organic ligands or inorganic shell materials, or by fabricating perovskite-polymer nanocomposites. These methods require complex processes and have limited stability in ambient air and water. Furthermore, stable perovskite nanoparticles in the various chemical environments and high temperatures with high humidity have not been reported yet.

The research team in collaboration with Seoul National University develops siloxane-encapsulated perovskite nanoparticle composite films. Here, perovskite nanoparticles are chemically crosslinked with thermally stable siloxane molecules, thereby significantly improving the stability of the perovskite nanoparticles without the need for any additional protecting layer.

Siloxane-encapsulated perovskite nanoparticle composite films exhibited a high PLQY (> 70%) value, which can be maintained over 600 days in water, various chemicals (alcohol, strong acidic and basic solutions), and high temperatures with high humidity (85℃/85%). The research team investigated the mechanisms impacting the chemical crosslinking and water molecule-induced stabilization of perovskite nanoparticles through various photo-physical analysis and density-functional theory calculation.

The research team confirmed that displays based on their siloxane-perovskite nanoparticle composite films exhibited higher PLQY and a wider color gamut than those of Cd-based quantum dots and demonstrated perfect color converting properties on commercial mobile phone screens. Unlike what was commonly believed in the halide perovskite field, the composite films showed excellent bio-compatibility because the siloxane matrix prevents the toxicity of Pb in perovskite nanoparticle.

By using this technology, the instability of perovskite materials, which is the biggest challenge for practical applications, is greatly improved through simple encapsulation method.

“Perovskite nanoparticle is the only photoluminescent material that can meet the next generation display color standard. Nevertheless, there has been reluctant to commercialize it due to its moisture vulnerability. The newly developed siloxane encapsulation technology will trigger more research on perovskite nanoparticles as color conversion materials and will accelerate early commercialization,” Professor Bae said.

This work was supported by the Wearable Platform Materials Technology Center (WMC) of the Engineering Research Center (ERC) Project, and the Leadership Research Program funded by the National Research Foundation of Korea.

-Publication:

Junho Jang, Young-Hoon Kim, Sunjoon Park, Dongsuk Yoo, Hyunjin Cho, Jinhyeong Jang, Han Beom Jeong, Hyunhwan Lee, Jong Min Yuk, Chan Beum Park, Duk Young Jeon, Yong-Hyun Kim, Byeong-Soo Bae, and Tae-Woo Lee. “Extremely Stable Luminescent Crosslinked Perovskite Nanoparticles under Harsh Environments over 1.5 Years” Advanced Materials, 2020, 2005255. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202005255.

Link to download the full-text paper:

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/adma.202005255

-Profile: Prof. Byeong-Soo Bae (Corresponding author)

bsbae@kaist.ac.kr

Lab. of Optical Materials & Coating

Department of Materials Science and Engineering

Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST)

2020.12.29 View 13683 -

Astrocytes Eat Connections to Maintain Plasticity in Adult Brains

Developing brains constantly sprout new neuronal connections called synapses as they learn and remember. Important connections — the ones that are repeatedly introduced, such as how to avoid danger — are nurtured and reinforced, while connections deemed unnecessary are pruned away. Adult brains undergo similar pruning, but it was unclear how or why synapses in the adult brain get eliminated.

Now, a team of KAIST researchers has found the mechanism underlying plasticity and, potentially, neurological disorders in adult brains. They published their findings on December 23 in Nature.

“Our findings have profound implications for our understanding of how neural circuits change during learning and memory, as well as in diseases,” said paper author Won-Suk Chung, an assistant professor in the Department of Biological Sciences at KAIST. “Changes in synapse number have strong association with the prevalence of various neurological disorders, such as autism spectrum disorder, schizophrenia, frontotemporal dementia, and several forms of seizures.”

Gray matter in the brain contains microglia and astrocytes, two complementary cells that, among other things, support neurons and synapses. Microglial are a frontline immunity defense, responsible for eating pathogens and dead cells, and astrocytes are star-shaped cells that help structure the brain and maintain homeostasis by helping to control signaling between neurons. According to Professor Chung, it is generally thought that microglial eat synapses as part of its clean-up effort in a process known as phagocytosis.

“Using novel tools, we show that, for the first time, it is astrocytes and not microglia that constantly eliminate excessive and unnecessary adult excitatory synaptic connections in response to neuronal activity,” Professor Chung said. “Our paper challenges the general consensus in this field that microglia are the primary synapse phagocytes that control synapse numbers in the brain.”

Professor Chung and his team developed a molecular sensor to detect synapse elimination by glial cells and quantified how often and by which type of cell synapses were eliminated. They also deployed it in a mouse model without MEGF10, the gene that allows astrocytes to eliminate synapses. Adult animals with this defective astrocytic phagocytosis had unusually increased excitatory synapse numbers in the hippocampus. Through a collaboration with Dr. Hyungju Park at KBRI, they showed that these increased excitatory synapses are functionally impaired, which cause defective learning and memory formation in MEGF10 deleted animals.

“Through this process, we show that, at least in the adult hippocampal CA1 region, astrocytes are the major player in eliminating synapses, and this astrocytic function is essential for controlling synapse number and plasticity,” Chung said.

Professor Chung noted that researchers are only beginning to understand how synapse elimination affects maturation and homeostasis in the brain. In his group’s preliminary data in other brain regions, it appears that each region has different rates of synaptic elimination by astrocytes. They suspect a variety of internal and external factors are influencing how astrocytes modulate each regional circuit, and plan to elucidate these variables.

“Our long-term goal is understanding how astrocyte-mediated synapse turnover affects the initiation and progression of various neurological disorders,” Professor Chung said. “It is intriguing to postulate that modulating astrocytic phagocytosis to restore synaptic connectivity may be a novel strategy in treating various brain disorders.”

This work was supported by the Samsung Science & Technology Foundation, the National Research Foundation of Korea, and the Korea Brain Research Institute basic research program.

Other contributors include Joon-Hyuk Lee and Se Young Lee, Department of Biological Sciences, Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST); Ji-young Kim, Hyoeun Lee and Hyungju Park; Research Group for Neurovascular Unit, Korea Brain Research Institute (KBRI); Seulgi Noh, and Ji Young Mun, Research Group for Neural Circuit, KBRI. Kim, Noh and Park are also affiliated with the Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences, Daegu Gyeongbuk Institute of Science and Technology (DGIST).

-Profile

Professor Won-Suk Chung

Department of Biological Sciences

Gliabiology Lab (https://www.kaistglia.org/)

KAIST

-Publication

"Astrocytes phagocytose adult hippocampal synapses for circuit homeostasis"

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-03060-3

2020.12.24 View 12008

Astrocytes Eat Connections to Maintain Plasticity in Adult Brains

Developing brains constantly sprout new neuronal connections called synapses as they learn and remember. Important connections — the ones that are repeatedly introduced, such as how to avoid danger — are nurtured and reinforced, while connections deemed unnecessary are pruned away. Adult brains undergo similar pruning, but it was unclear how or why synapses in the adult brain get eliminated.

Now, a team of KAIST researchers has found the mechanism underlying plasticity and, potentially, neurological disorders in adult brains. They published their findings on December 23 in Nature.

“Our findings have profound implications for our understanding of how neural circuits change during learning and memory, as well as in diseases,” said paper author Won-Suk Chung, an assistant professor in the Department of Biological Sciences at KAIST. “Changes in synapse number have strong association with the prevalence of various neurological disorders, such as autism spectrum disorder, schizophrenia, frontotemporal dementia, and several forms of seizures.”

Gray matter in the brain contains microglia and astrocytes, two complementary cells that, among other things, support neurons and synapses. Microglial are a frontline immunity defense, responsible for eating pathogens and dead cells, and astrocytes are star-shaped cells that help structure the brain and maintain homeostasis by helping to control signaling between neurons. According to Professor Chung, it is generally thought that microglial eat synapses as part of its clean-up effort in a process known as phagocytosis.

“Using novel tools, we show that, for the first time, it is astrocytes and not microglia that constantly eliminate excessive and unnecessary adult excitatory synaptic connections in response to neuronal activity,” Professor Chung said. “Our paper challenges the general consensus in this field that microglia are the primary synapse phagocytes that control synapse numbers in the brain.”

Professor Chung and his team developed a molecular sensor to detect synapse elimination by glial cells and quantified how often and by which type of cell synapses were eliminated. They also deployed it in a mouse model without MEGF10, the gene that allows astrocytes to eliminate synapses. Adult animals with this defective astrocytic phagocytosis had unusually increased excitatory synapse numbers in the hippocampus. Through a collaboration with Dr. Hyungju Park at KBRI, they showed that these increased excitatory synapses are functionally impaired, which cause defective learning and memory formation in MEGF10 deleted animals.

“Through this process, we show that, at least in the adult hippocampal CA1 region, astrocytes are the major player in eliminating synapses, and this astrocytic function is essential for controlling synapse number and plasticity,” Chung said.

Professor Chung noted that researchers are only beginning to understand how synapse elimination affects maturation and homeostasis in the brain. In his group’s preliminary data in other brain regions, it appears that each region has different rates of synaptic elimination by astrocytes. They suspect a variety of internal and external factors are influencing how astrocytes modulate each regional circuit, and plan to elucidate these variables.

“Our long-term goal is understanding how astrocyte-mediated synapse turnover affects the initiation and progression of various neurological disorders,” Professor Chung said. “It is intriguing to postulate that modulating astrocytic phagocytosis to restore synaptic connectivity may be a novel strategy in treating various brain disorders.”

This work was supported by the Samsung Science & Technology Foundation, the National Research Foundation of Korea, and the Korea Brain Research Institute basic research program.

Other contributors include Joon-Hyuk Lee and Se Young Lee, Department of Biological Sciences, Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST); Ji-young Kim, Hyoeun Lee and Hyungju Park; Research Group for Neurovascular Unit, Korea Brain Research Institute (KBRI); Seulgi Noh, and Ji Young Mun, Research Group for Neural Circuit, KBRI. Kim, Noh and Park are also affiliated with the Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences, Daegu Gyeongbuk Institute of Science and Technology (DGIST).

-Profile

Professor Won-Suk Chung

Department of Biological Sciences

Gliabiology Lab (https://www.kaistglia.org/)

KAIST

-Publication

"Astrocytes phagocytose adult hippocampal synapses for circuit homeostasis"

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-03060-3

2020.12.24 View 12008 -

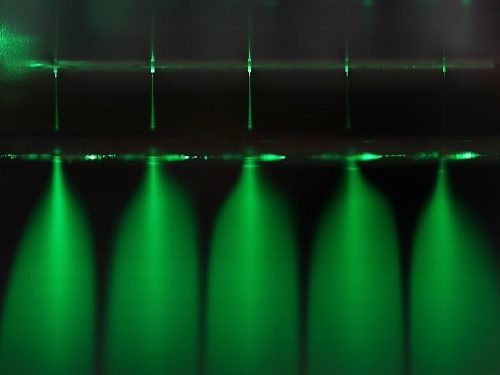

Electrosprayed Micro Droplets Help Kill Bacteria and Viruses

With COVID-19 raging around the globe, researchers are doubling down on methods for developing diverse antimicrobial technologies that could be effective in killing a virus, but harmless to humans and the environment.

A recent study by a KAIST research team will be one of the responses to such efforts. Professor Seung Seob Lee and Dr. Ji-hun Jeong from the Department of Mechanical Engineering developed a harmless air sterilization prototype featuring electrosprayed water from a polymer micro-nozzle array. This study is one of the projects being supported by the KAIST New Deal R&D Initiative in response to COVID-19. Their study was reported in Polymer.

The electrosprayed microdroplets encapsulate reactive oxygen species such as hydroxyl radicals, superoxides that are known to have an antimicrobial function. The encapsulation prolongs the life of reactive oxygen species, which enable the droplets to perform their antimicrobial function effectively. Prior research has already proven the antimicrobial and encapsulation effects of electrosprayed droplets.

Despite its potential for antimicrobial applications, electrosprayed water generally operates under an electrical discharge condition, which can generate ozone. The inhalation of ozone is known to cause damage to the respiratory system of humans. Another technical barrier for electrospraying is the low flow rate problem. Since electrospraying exhibits the dependence of droplet size on the flow rate, there is a limit for the amount of water microdroplets a single nozzle can produce.

With this in mind, the research team developed a dielectric polymer micro-nozzle array to perform the multiplexed electrospraying of water without electrical discharge. The polymer micro-nozzle array was fabricated using the MEMS (Micro Electro-Mechanical System) process. According to the research team, the nozzle can carry five to 19 micro-nozzles depending on the required application.

The high aspect ratio of the micro-nozzle and an in-plane extractor were proposed to concentrate the electric field at the tip of the micro-nozzle, which prevents the electrical discharge caused by the high surface tension of water. A micro-pillar array with a hydrophobic coating around the micro-nozzle was also proposed to prevent the wetting of the micro-nozzle array.

The polymer micro-nozzle array performed in steady cone jet mode without electrical discharge as confirmed by high-speed imaging and nanosecond pulsed imaging. The water microdroplets were measured to be in the range of six to 10 μm and displayed an antimicrobial effect on Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus.

Professor Lee said, “We believe that this research can be applied to air conditioning products in areas that require antimicrobial and humidifying functions.”

Publication:

Jeong, J. H., et al. (2020) Polymer micro-atomizer for water electrospray in the cone jet mode. Polymer. Vol. No. 194, 122405. Available online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polymer.2020.122405

Profile: Seung Seob Lee, Ph.D.

sslee97@kaist.ac.kr

http://mmst.kaist.ac.kr/

Professor

Department of Mechanical Engineering (ME)

Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST)

https://www.kaist.ac.kr

Daejeon 34141, Korea

Profile: Ji-hun Jeong, Ph.D.

jiuni6022@kaist.ac.kr

Postdoctoral researcher

Department of Mechanical Engineering (ME)

Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST)

https://www.kaist.ac.kr

Daejeon 34141, Korea

(END)

2020.12.21 View 13751

Electrosprayed Micro Droplets Help Kill Bacteria and Viruses

With COVID-19 raging around the globe, researchers are doubling down on methods for developing diverse antimicrobial technologies that could be effective in killing a virus, but harmless to humans and the environment.

A recent study by a KAIST research team will be one of the responses to such efforts. Professor Seung Seob Lee and Dr. Ji-hun Jeong from the Department of Mechanical Engineering developed a harmless air sterilization prototype featuring electrosprayed water from a polymer micro-nozzle array. This study is one of the projects being supported by the KAIST New Deal R&D Initiative in response to COVID-19. Their study was reported in Polymer.

The electrosprayed microdroplets encapsulate reactive oxygen species such as hydroxyl radicals, superoxides that are known to have an antimicrobial function. The encapsulation prolongs the life of reactive oxygen species, which enable the droplets to perform their antimicrobial function effectively. Prior research has already proven the antimicrobial and encapsulation effects of electrosprayed droplets.

Despite its potential for antimicrobial applications, electrosprayed water generally operates under an electrical discharge condition, which can generate ozone. The inhalation of ozone is known to cause damage to the respiratory system of humans. Another technical barrier for electrospraying is the low flow rate problem. Since electrospraying exhibits the dependence of droplet size on the flow rate, there is a limit for the amount of water microdroplets a single nozzle can produce.

With this in mind, the research team developed a dielectric polymer micro-nozzle array to perform the multiplexed electrospraying of water without electrical discharge. The polymer micro-nozzle array was fabricated using the MEMS (Micro Electro-Mechanical System) process. According to the research team, the nozzle can carry five to 19 micro-nozzles depending on the required application.

The high aspect ratio of the micro-nozzle and an in-plane extractor were proposed to concentrate the electric field at the tip of the micro-nozzle, which prevents the electrical discharge caused by the high surface tension of water. A micro-pillar array with a hydrophobic coating around the micro-nozzle was also proposed to prevent the wetting of the micro-nozzle array.

The polymer micro-nozzle array performed in steady cone jet mode without electrical discharge as confirmed by high-speed imaging and nanosecond pulsed imaging. The water microdroplets were measured to be in the range of six to 10 μm and displayed an antimicrobial effect on Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus.

Professor Lee said, “We believe that this research can be applied to air conditioning products in areas that require antimicrobial and humidifying functions.”

Publication:

Jeong, J. H., et al. (2020) Polymer micro-atomizer for water electrospray in the cone jet mode. Polymer. Vol. No. 194, 122405. Available online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polymer.2020.122405

Profile: Seung Seob Lee, Ph.D.

sslee97@kaist.ac.kr

http://mmst.kaist.ac.kr/

Professor

Department of Mechanical Engineering (ME)

Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST)

https://www.kaist.ac.kr

Daejeon 34141, Korea

Profile: Ji-hun Jeong, Ph.D.

jiuni6022@kaist.ac.kr

Postdoctoral researcher

Department of Mechanical Engineering (ME)

Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST)

https://www.kaist.ac.kr

Daejeon 34141, Korea

(END)

2020.12.21 View 13751 -

Researchers Report Longest-lived Aqueous Flow Batteries

New technology to overcome the life limit of next-generation water-cell batteries

A research team led by Professor Hee-Tak Kim from the Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering has developed water-based zinc/bromine redox flow batteries (ZBBs) with the best life expectancy among all the redox flow batteries reported by identifying and solving the deterioration issue with zinc electrodes.

Professor Kim, head of the Advanced Battery Center at KAIST's Nano-fusion Research Institute, said, "We presented a new technology to overcome the life limit of next-generation water-cell batteries. Not only is it cheaper than conventional lithium-ion batteries, but it can contribute to the expansion of renewable energy and the safe supply of energy storage systems that can run with more than 80 percent energy efficiency."

ZBBs were found to have stable life spans of more than 5,000 cycles, even at a high current density of 100 mA/cm2. It was also confirmed that it represented the highest output and life expectancy compared to Redox flow batteries (RFBs) reported worldwide, which use other redox couples such as zinc-bromine, zinc-iodine, zinc-iron, and vanadium.

Recently, more attention has been focused on energy storage system (ESS) that can improve energy utilization efficiency by storing new and late-night power in large quantities and supplying it to the grid if necessary to supplement the intermittent nature of renewable energy and meet peak power demand.

However, lithium-ion batteries (LIBs), which are currently the core technology of ESSs, have been criticized for not being suitable for ESSs, which store large amounts of electricity due to their inherent risk of ignition and fire. In fact, a total of 33 cases of ESSs using LIBs in Korea had fire accidents, and 35% of all ESS facilities were shut down. This is estimated to have resulted in more than 700 billion won in losses.

As a result, water-based RFBs have drawn great attention. In particular, ZBBs that use ultra-low-cost bromide (ZnBr2) as an active material have been developed for ESSs since the 1970s, with their advantages of high cell voltage, high energy density, and low price compared to other RFBs. Until now, however, the commercialization of ZBBs has been delayed due to the short life span caused by the zinc electrodes. In particular, the uneven "dendrite" growth behavior of zinc metals during the charging and discharging process leads to internal short circuits in the battery which shorten its life.

The research team noted that self-aggregation occurs through the surface diffusion of zinc nuclei on the carbon electrode surface with low surface energy, and determined that self-aggregation was the main cause of zinc dendrite formation through quantum mechanics-based computer simulations and transmission electron microscopy. Furthermore, it was found that the surface diffusion of the zinc nuclei was inhibited in certain carbon fault structures so that dendrites were not produced.

Single vacancy defect, where one carbon atom is removed, exchanges zinc nuclei and electrons, and is strongly coupled, thus inhibiting surface diffusion and enabling uniform nuclear production/growth. The research team applied carbon electrodes with high density fault structure to ZBBs, achieving life characteristics of more than 5,000 cycles at a high charge current density (100 mA/cm2), which is 30 times that of LIBs.

This ESS technology, which can supply eco-friendly electric energy such as renewable energy to the private sector through technology that can drive safe and cheap redox flow batteries for long life, is expected to draw attention once again.

Publication:

Ju-Hyuk Lee, Riyul Kim, Soohyun Kim, Jiyun Heo, Hyeokjin Kwon, Jung Hoon Yang, and Hee-Tak Kim. 2020. Dendrite-free Zn electrodeposition triggered by interatomic orbital hybridization of Zn and single vacancy carbon defects for aqueous Zn-based flow batteries. Energy and Environmental Science, 2020, 13, 2839-2848.

Link to download the full-text paper:http://xlink.rsc.org/?DOI=D0EE00723D

Profile: Prof. Hee-Tak Kimheetak.kim@kaist.ac.krhttp://eed.kaist.ac.krAssociate ProfessorDepartment of Chemical & Biomolecular EngineeringKAIST

2020.12.16 View 13517

Researchers Report Longest-lived Aqueous Flow Batteries

New technology to overcome the life limit of next-generation water-cell batteries

A research team led by Professor Hee-Tak Kim from the Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering has developed water-based zinc/bromine redox flow batteries (ZBBs) with the best life expectancy among all the redox flow batteries reported by identifying and solving the deterioration issue with zinc electrodes.

Professor Kim, head of the Advanced Battery Center at KAIST's Nano-fusion Research Institute, said, "We presented a new technology to overcome the life limit of next-generation water-cell batteries. Not only is it cheaper than conventional lithium-ion batteries, but it can contribute to the expansion of renewable energy and the safe supply of energy storage systems that can run with more than 80 percent energy efficiency."

ZBBs were found to have stable life spans of more than 5,000 cycles, even at a high current density of 100 mA/cm2. It was also confirmed that it represented the highest output and life expectancy compared to Redox flow batteries (RFBs) reported worldwide, which use other redox couples such as zinc-bromine, zinc-iodine, zinc-iron, and vanadium.

Recently, more attention has been focused on energy storage system (ESS) that can improve energy utilization efficiency by storing new and late-night power in large quantities and supplying it to the grid if necessary to supplement the intermittent nature of renewable energy and meet peak power demand.

However, lithium-ion batteries (LIBs), which are currently the core technology of ESSs, have been criticized for not being suitable for ESSs, which store large amounts of electricity due to their inherent risk of ignition and fire. In fact, a total of 33 cases of ESSs using LIBs in Korea had fire accidents, and 35% of all ESS facilities were shut down. This is estimated to have resulted in more than 700 billion won in losses.